Human Factors Engineering

By Lori Moore, MPH, BSN, RN, MSCE

Hand hygiene is an important evidence-based practice that spans across all hierarchies and disciplines.

Despite the evidence and numerous guidelines for proper hand hygiene, healthcare workers (HCW), on average, clean their hands less than half of the times they should.1 When hand hygiene improvement efforts fall short, the typical focus is on the behavior of HCW providing more training, more education and encouraging them to do better. This approach often referred to as the “name, blame and train mentality” creates a poor working environment, misdirects scarce resources, and perpetuates the problem. At its very core, hand hygiene noncompliance is not a people problem. It is a system problem. If you want to improve hand hygiene, you need to work to improve the system that enables the continuation of noncompliance with hand hygiene best practices.

Human factors (HF) is a scientific discipline that takes into consideration not only people, but also the systems in which they work. A HF approach examines the interactions between people, the tasks they perform, the tools and technologies that they use, the physical environment within which the tasks are performed, and other organizational conditions (both internal and external).2 These interactions are important because they influence behaviors, performance, and outcomes. A central goal in using a HF approach is to design the elements within a system (e.g., tools, technologies, tasks, environment, organization) to fit the person and their capabilities and limitations, not the person to the system. We cannot redesign people, but we can redesign the systems within which people work to ensure safety, effectiveness and ease of use, essentially making it easier to do the right thing.

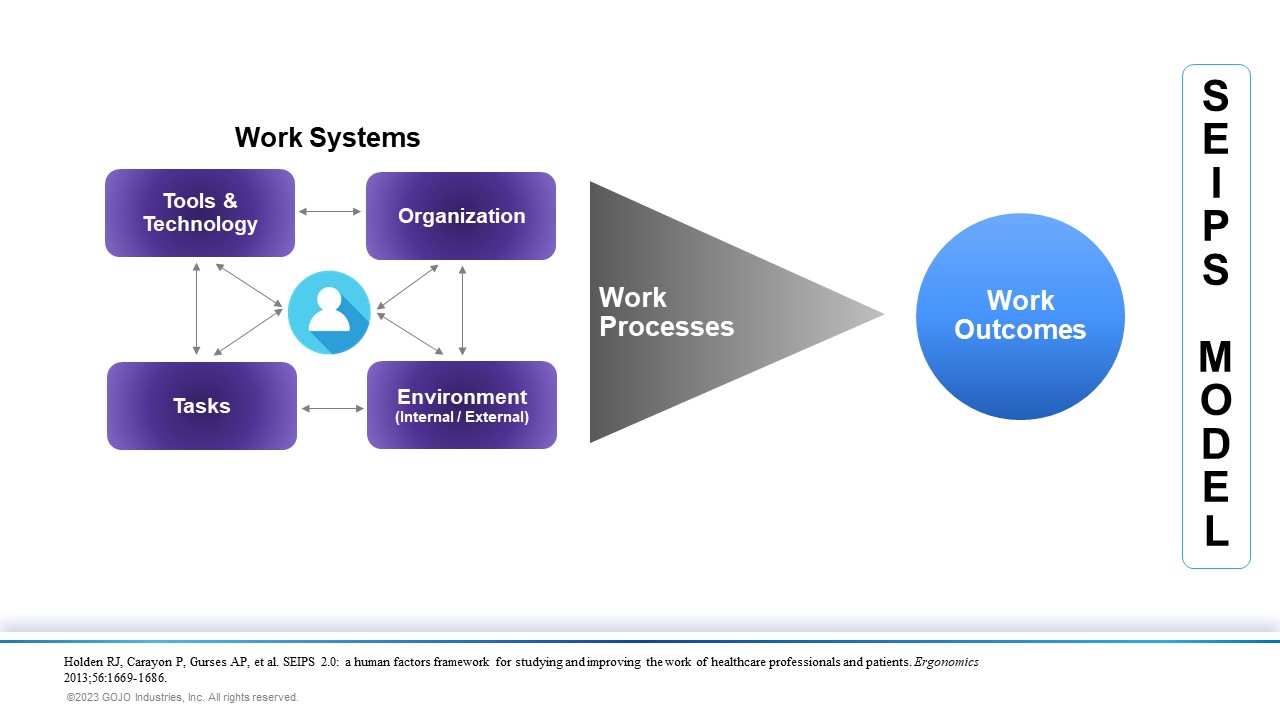

The SEIPS (Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety) model2 is a HF systems approach that has been successfully applied in healthcare to improve patient safety and quality of care. According to this model, the work system in which care is provided affects both the work that is performed and the clinical care processes that are carried out, which in turn influence outcomes (Figure 1). SEIPS prompts us to look beyond linear cause and effect relationships (name, blame and train mentality) and examine bilateral interactions between people and various work system elements, broadening the focus on wider system issues, not just individuals.

The SEIPS model can be used as a framework to study the task of hand hygiene to better understand how skill demands, physical demands, mental workload, team dynamics, aspects of the work environment and devices (e.g., dispensers) impact the ability of HCW to consistently complete the task.3 Essentially, this approach focuses on how the system works in real-life, identifying how interactions between people and other elements in the system facilitate or hinder optimal performance.

As an example, the interaction between HCW (person) and the alcohol-based hand rub dispensers (tools) that are necessary to complete hand hygiene (task) can be facilitated or hindered by both the layout of the patient’s room and the placement of the dispenser. Recommendations for placement include easily visible and unobstructed access at the entrance of patient rooms as well as inside the patient room within arm’s reach of the workflow where care takes place.4-6 However, placement of dispensers is often not considered when planning the design and layout of patient rooms, potentially limiting wall space options inside the room. Additionally, standardization is important in work system design, and the placement of dispensers is often not consistent in each patient room. Having dispensers located in a standardized location in each patient room encourages habit formation by eliminating the need for decision making and searching around looking for a dispenser to carry out the task.5

The SEIPS model importantly emphasizes another key concept, that of balance, noting that changes to any aspect of the work system will either negatively or positively affect the work and clinical processes and consequently the outcomes.2,7 This concept of balance becomes an important factor in hand hygiene improvement initiatives. Published literature has reported that there is a negative correlation between the number of hand hygiene opportunities and hand hygiene performance rates8-9 (i.e., as opportunities increase, performance rates decrease) suggesting that an increase in hand hygiene workload creates an imbalance in the work system leading to a barrier in optimal performance. This in turn requires adaptations in other elements of the work system to reinstate balance.

Improving hand hygiene compliance is a challenge for all healthcare facilities. Interventions that do not consider issues across the whole system are unlikely to have a significant sustainable impact. The application of a HF approach is an underutilized resource in the identification of systemic contributions to the continuation of noncompliance with hand hygiene best practices.

Lori Moore, Clinical Educator, spent 10yrs. as a frontline nurse before joining GOJO in 2013. She’s a passionate patient safety and IP advocate.

References

- Erasmus, V, Daha TJ, Brug H, et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:283-294.

- Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669-1686.

- Pennathur PR, Herwaldt LA. Role of Human Factors Engineering in Infection Prevention: Gaps and Opportunities. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2017;9(2):230-249.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

- Cure L, Van Enk R. Effect of hand sanitizer location on hand hygiene compliance. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:917-921.

- Glowicz JB, Landon E, Sickbert-Bennett EE, et al. SHEA/IDSA/APIC Practice Recommendation: Strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections through hand hygiene: 2022 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20423;44:355-376.

- Carayon, P, Xie, A, Kianfar. Human factors and ergonomics as a patient safety practice. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:196-205.

- Pittet D, Mourouga P, Perneger TV. Compliance with hand washing in a teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:126-130.

- Chang NN, Schweizer ML, Reisinger HS, et al. The impact of workload on hand hygiene compliance: Is 100% compliance achievable? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022;43:1259-1261.

Reference for Figure 1

Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669-1686.