We Can All Define Patient Safety… or Can We?

March / April 2012

![]()

We Can All Define Patient Safety… or Can We?

Patient safety is a term used frequently in healthcare… perhaps too frequently, and sometimes without appropriate context. An exploratory survey was conducted at the Estes Park Institute conferences in the 2009–2010 season to probe the definition of patient safety among hospital executives, board members, and physician leaders. Participants were given 3 to 4 minutes to define patient safety with up to 10 single words. The top three single-word definitions were communication, falls, and quality.

There were more than 4,200 word definitions from 647 individuals. The resulting word-definitions ran the gamut without any clear winners or patterns. No distinguishing characteristics were found between the words selected by hospital executives, board members, and physician leaders. Similar exercises can be used by teams and organizations to probe the clarity of their patient safety goals and understanding of their purpose. The results of our study lead us to question whether an unintended consequence and barrier of our over-encompassing “patient safety” efforts is that the execution of “patient safety” in organizations now suffers from being a buzzword without a shared mental model of objectives, structure, and process.

|

Estes Park Institute Since 1974, the Estes Park Institute (www.estespark.org), Englewood, Colorado, has been dedicated to helping healthcare professionals explore current trends, innovations, and solutions in healthcare. Estes Park has been a long-time advocate for change. Through its current work with the CMS Innovation Center, Estes Park is sharing its vision for delivery system and reimbursement changes. |

Ever since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its landmark report in 2000, patient safety has ranked among the top-of-mind issues for healthcare leaders, regulatory bodies, and payors. Yet, at the 10-year anniversary of the report, Consumer’s Union (2009) gave America a failing grade when it came to patient safety, admonishing that, “despite initial flurry of activity, progress slowed once the media moved on to the next crisis….” Despite preventable deaths from medical errors at hospitals, which far outnumber the annual number of deaths from motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, and AIDS/HIV, patient safety receives transient and episodic attention following a notable or newsworthy event that calls attention to the issue. Other anniversary commentaries also gave only guarded praise while reflecting on the 10-year journey (Wachter, 2010). Perhaps even more sobering are the results published in late 2010 from studies by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) (2010, November) and Landrigan et al. (2010). Both studies provide sparse evidence of patient safety “improvement” or the reduction of the incidence of harm since 1999.

This lack of progress is sobering in the face of physician leaders, healthcare executives, and board members visibly increasing their work, agenda, and attention on patient safety. These leaders maintain that patient safety is one of the top if not the top issue reflecting the organization’s will, attention, and resources. They also believe that patient safety is not as difficult to achieve as other pressing issues facing hospitals (Estes Park, 2012). Patient safety committees have sprung up at the hospital operational level and even at the board level. Newly appointed patient safety officers are participating and leading what can sometimes seem an overwhelming number of activities and initiatives. Large investments are being made to educate, alter workflow processes, and/or institute mitigating safeguards within care processes, sometimes without much evidence of effectiveness or success. This level of activity runs contrary to published research that indicates a lack of progress made to date.

The study we conducted at Estes Park Institute conferences in 2009 and 2010 probed into our understanding of the definitions of patient safety and provided us with insight into why our efforts to date have had limited progress or have stalled. Study data and results provide us a semi-quantitative means of offering recommendations for healthcare organizations to make forward progress at the organizational, physician leadership, and board level.

Methods

During the opening of a general session program discussing patient safety, participants at each of six Estes Park Institute conferences in the 2009–2010 season were asked to list 10 single-word definitions of the term patient safety. Specifically, the script was as follows:

Define patient safety with a one-word definition. No long prose or word smithing… just one-word definitions. You may come up with up to 10. You have 3 to 4 minutes…

GO! Remember, only one-word definitions.

The participants—predominantly board members, hospital executives and physician leaders from community hospitals—were attending a 5-day conference on hospital governance and leadership, which was part of the Estes Park Institute 2009-2010 season. These healthcare leaders had previously listed patient safety as a leading issue of concern.

Participants were given 3 to 4 minutes to create their lists. The lists were collected and analyzed for frequency, frequency by role (i.e. board member, hospital executive, or physician leader), and word rank (i.e. first word listed).

Results

A total of 647 lists were collected and analyzed. More than 4,200 words were used as definitions. From this list, 1,270 unique words were identified. The top 10 words used to define patient safety (shown with their percentage of occurrence) were the following:

1. Communication 3.45%

2. Falls 2.64%

3. Quality 2.10%

4. Timely 1.65%

5. Medications 1.30%

6. Care 1.25%

7. Outcomes 1.18%

8. Accurate 1.18%

9. Appropriate 0.99%

10. Trust 0.99%

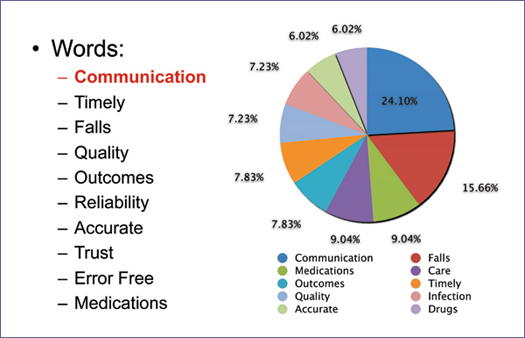

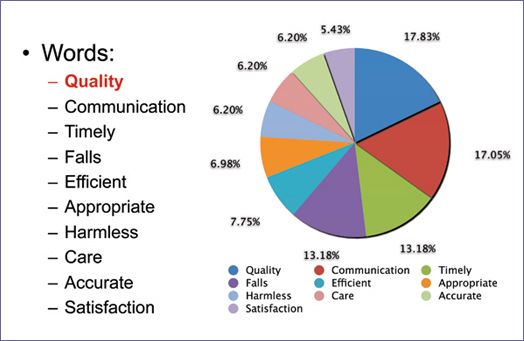

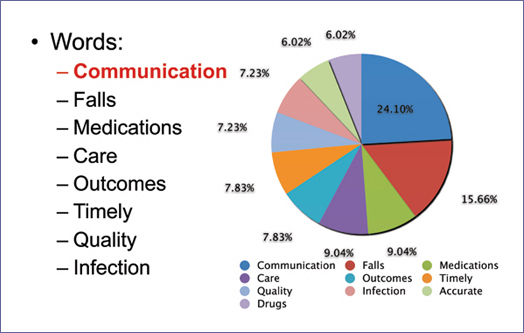

Figures 1, 2, and 3 provide separate pie-graph analyses of the words defined by hospital executives, physician leaders, and board members. Participants self-designated their roles as executive, physician, or board member. To avoid double counting, physicians who indicated that they were both a physician and a hospital executive with a C-suite position (e.g. CEO) were placed in the executive group for analysis. Physicians who indicated that they were both a physician and a board member were placed in the physician leader group for analysis.

Figure 2: Top 10 Words Used to Define Patient Safety by Physician Leaders

Figure 3: Top 10 Words Used to Define Patient Safety by Board Members

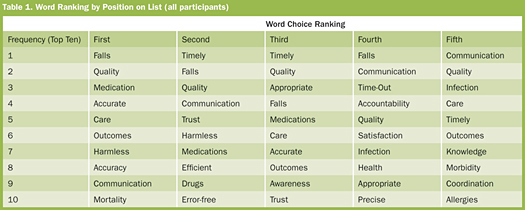

Analysis was also made of word ranking by position on the lists for all participants. The words that appeared first through fifth on the lists are found in Table 1.

Discussion

A shared mental model is a well-defined, highly organized, dynamic knowledge of objectives, goals, structures, and processes. These models are generally developed over periods of time, creating patterns that facilitate informed decision-making for an individual, a team, or an organization. Is there a shared mental model around those who are working on patient safety in your organization? How many patient safety advocates do you have at your organization? When a healthcare leader addresses the topic of “patient safety” with the board, hospital staff, physician groups, media, and consumer groups, what is each person really thinking about? What defines patient safety for each of us?

The results of this exploratory survey were surprising on several levels. First, there was no winner or set of winners. It was startling that more than 4,200 words were used to define patient safety. Whether the results were analyzed from a rank order or a frequency perspective, no single word or words stood out.

After individuals completed their definition lists, we asked them to form groups of approximately 6 to10 people. They were asked to determine in these smaller groups, if any common words emerged on the list of every person in their group (i.e. all 10 people in the group would have the same word on their individual lists). When polled as an entire audience, the participants expected that at least 3 to 6 words would likely be in common. Yet, not a single small group could identify even one common word. This finding is particularly eye-opening, knowing that participants from the same organization tend to sit together at these conferences. The small groups would tend to be more indicative of an organizational cluster and representative of their culture. That is, being from a common organization, they would be more familiar, sharing a common organizational dashboard or set of goals around patient safety than those from disparate organizations. This familiarity would predict common word definitions.

In fact, in one instance, the CEO (with an RN background) was amazed to find that he and his chief nursing officer (CNO) did not have a single word in common on their two lists. Despite having a common professional background and hospital strategic plan—complete with patient safety goals, aims, and measurements, that they had worked on together—they had 20 different word definitions between them. The lack of a common definition in this case, as well as in the small groups, demonstrates the “buzz” that has occurred around patient safety. These wide sets of definitions may in part be what underpins the current lack of strength in positioning patient safety initiatives that is prevalent within organizations championing patient safety. A particularly provocative finding in the study is that only about 2% of the respondents associated safety with the concept of quality. In recent times it has become clear from payor-based payment initiatives that quality measures have become the stick for driving safety initiatives at organizations.

Second, these one-word definitions are the ones that came immediately to mind—without the benefit of wordsmithing by respondents. They covered a wide range of descriptions from extremely concrete tasks (e.g. time-out), to concrete categories (e.g. falls, hospital-acquired infections) to very broad and abstract concepts and attributes with elusive measurement (e.g. trust, care).

Third, there were no definable patterns distinguished by the roles of board member, hospital executive, or physician leader. One might hypothesize that as clinicians, physician leaders might have a tendency for more concrete definitions, but their highest ranking words in this exercise were quality, communication, and timely.

The one word that did appear in the top three on the frequency lists from all three groups and all participants was communication. However, communication, despite its frequency, did not show up until ninth in terms of the first word to come to mind in the rank list.

It is clear from this simple study that more work is needed for top-of-mind positioning when it comes to patient safety at the highest levels within our healthcare institutions.

Summary

The term patient safety is very abstract, and therefore carries a vast set of definitions. National organizations have well-scripted definitions, but even at the national level, there is a lack of standard data definitions and elements (Henriksen et al., 2008). A study by Classen, et.al.(2011) recently challenged the sensitivity of well-subscribed patient safety indicators. Our current study demonstrates that notwithstanding the challenges at the national level, the standard definitions are likely to be just as challenging and varied at the individual level.

One of the reasons that a patient safety journey may stall is that these widely disparate definitions result in diluted efforts and loss of focus. Frustration ensues, with some individuals interested in very specific, concrete, and measurable tasks while others are striving for elusive, cultural concepts. To gain traction and demonstrate measurable improvement, patient safety should not attempt to cover items from soup to nuts. Yet in some organizations, it has come to that, and the lack of boundaries creates confusion.

The results of this exploratory survey are provocative for physician leaders, healthcare organizations, teams, policy makers, and even consumer groups. The survey can be easily replicated as an exercise. Leaders can identify the broad range of definitions within teams, probe differences, seek common themes, and ultimately provide more clarity and common purpose. Although a wide set of definitions will likely be identified—similar to our experience—the resulting lists themselves are not the endpoint. Conversations should take place following review of the word lists. The clarity of a shared mental model that can then emerge will provide the necessary traction and breakthrough.

In April of 2011, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius launched the Partnership for Patients, leveraging private-public partnerships to focus on patient safety nationwide. As we develop these new partnerships that we need in the current healthcare environment, the dangers of confusing definitions and mental models become even more worrisome. If a community hospital’s governance and leadership team have a wide set of definitions, we must consider how that diversity would become even more complex when adding new private and public partners (e.g. long-term care, home health, health plan, government health agencies).

No doubt, patient safety will continue to be a front-page issue for healthcare leaders. We urge organizations to take a step back and consider all the places/committees/roles/initiatives where they are using the term patient safety. Avoid simply using the term patient safety. Realize that in doing so, whether the audience is a small group of six or a larger audience, what is being defined in each person’s mind is likely to be different. Instead, carefully and explicitly define a common signal and goal in order to accelerate, focus, and align the work at hand.

Della Lin is an anesthesiologist in Honolulu and is a leadership consultant in patient safety, quality improvement, and transformational change. She is senior fellow in patient safety and system design with the Estes Park Institute. As part of her commitment and passion in the field of patient safety she was an inaugural NPSF-HRET Patient Safety Leadership Fellow (2002) and is a frequent keynote spea ker, teacher, and author. Lin may be contacted at dlinmdconsult@yahoo.com.

Sanjaya Kumar is chief medical officer and product strategist at XStor Systems, Inc. In his role as CMO, Kumar closely directs the product vision and workflow for all XStor products in the field of image storage management. Kumar is a widely recognized as a thought leader in the area of patient safety and continuous quality improvement methodologies. He is an author of two books and is widely published in peer-reviewed journals and in healthcare trade publications.

Further Reading

The National Patient Safety Foundation has published a related article by Della Lin, “Shared Mental Models Bring Clarity and a Common Purpose to Patient Safety Work,” (2011) in Focus on Patient Safety, 14(4).