Virtual Patient Platforms

May / June 2012

![]()

Virtual Patient Platforms

Virtual patients offer a range of possible clinical situations and explore how caregivers’ decisions impact patient outcomes.

Clinical decision-making skills are among the most valuable assets healthcare professionals possess, but they are also one of the hardest aspects of medicine to teach, learn, and hone. For most caregivers, gaining the skills and experience they need comes from interaction with actual patients, and this approach requires healthcare professionals to strike a delicate balance—one where educational needs are carefully weighed against potential safety issues, and time spent in real-world settings is preceded by countless hours of classroom preparation and instruction.

Times are rapidly changing, however, making this balance much more difficult to achieve. Newer reimbursement models mean patients now spend significantly less time in acute care settings and opportunities to see the entire duration of a case are few and far between. As a result, it’s much more challenging for providers at all educational levels to obtain the practice they need to best understand how various treatments affect patient outcomes both initially and over the long term.

In addition, growing patient safety and quality concerns following the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report, To Err Is Human (2000), further limit the amount of time caregivers can immerse themselves in true-to-life clinical environments to apply what they learned through lectures, conferences, journal articles, and the like.

Simulation is a proven educational technique that overcomes these obstacles, enabling medical schools, healthcare organizations and professional associations to develop and assess clinical decision-making skills in a safe, high-fidelity environment. Similar to how flight simulators allow even veteran pilots to practice unusual or difficult situations, virtual patients help healthcare professionals put all of their decision-making skills to the test.

The Advantages of Virtual Patients

Virtual patients complement traditional classroom instruction and enable educators, teachers, and other experts to create and distribute decision-based medical simulations for a range of educational needs. Defined as computer-based, interactive clinical scenarios, virtual cases are increasingly being recognized as a crucial component of case-based learning in the healthcare arena, and especially in problem-based learning situations. Nearly one-third of U.S.-based medical schools currently use virtual patients as well as numerous provider organizations (Huang, 2007).

Although the concept of virtual patients has been around since the 1970s, the introduction of the MedBiquitous Virtual Patient (MVP) standard in 2010 acted as a catalyst, and since then, interest in the technology has grown steadily both domestically and around the globe. This ANSI standard expands the potential uses of the technology while facilitating access to cases in the public domain.

What makes virtual patients unique is their ability to expose providers to a range of possible clinical situations and then explore exactly how their decisions would impact patient outcomes. Learners are able to make mistakes and explore the implications of those mistakes without harm to patients, unlike learning in clinical environments.

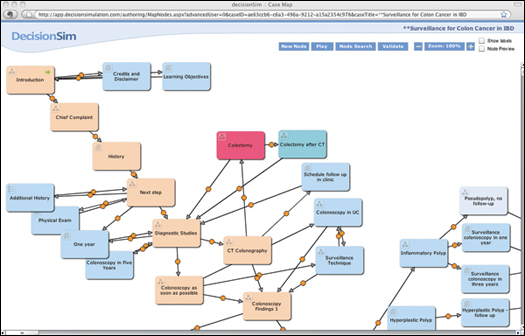

Figure 1. Branched-narrative virtual patients allow learners to receive personalized feedback based on their decisions as indicated in the node map.

As users progress through a case, they receive immediate, individualized feedback on each decision they make. If and when errors occur, learners have the opportunity to try again and practice those skills in need of improvement. Additionally, since cases are web-based and continuously available, they can be accessed as often as needed, whether from work, school, or home, and are easily incorporated into a provider’s busy schedule.

The advantages of virtual patient platforms extend to healthcare institutions as well. First and foremost, they reduce burdens on training resources, including clinical teachers and patients. They also allow organizations to cover content in areas where either they do not have an in-house expert or where the expert may have limited availability (Tworek, 2010). Equally important, these platforms collect rich, meaningful data as users move through each clinical scenario, ultimately allowing healthcare organizations to objectively assess a caregiver’s reasoning skills, gain insight into current practice behavior, and uncover gaps in knowledge.

How It Works

Historically, virtual cases have been notoriously difficult to create. For example, take a patient who comes in to the emergency department with severe headaches. Depending on the other symptoms present, there are a multitude of diagnostics and decisions a caregiver might make, all of which impact the outcome. Even further, one decision point yields a totally different path than another. In other words, there is a complex web with numerous branches that a learner needs to be able to explore for an authentic simulated case that mimics a real patient encounter—making virtual cases extremely complex to build.

To create virtual cases, authors use a variety of methods, such as working with a technical expert who captures the educator’s thoughts and then builds the case. Newer web-based virtual patient authoring applications enable the educator to build the simulation step-by-step, similar to how a PowerPoint presentation is developed.

Once the audience is identified and fundamentals are in place, a patient’s story may unfold in a number of different ways. Some platforms take a linear path to storytelling while others utilize a branched narrative methodology that is more complex and gives learners a greater degree of interactivity and control. Best described as a highly flexible decision tree, branched narrative platforms reproduce, through storytelling, a wide range of scenarios and variations that evolve over time based on the learner’s decision making—widely regarded as one of the best methods for teaching, practicing, and assessing clinical decision making (Cook & Triola, 2009).

Each approach offers benefits and allows authors to combine their personal experiences with proven techniques and clinical guidelines. By doing so, authors can expose learners to real-world case examples they might not encounter in other training, including those that may be too dangerous or unusual to be part of a typical curriculum, or one as simple as proper handwashing protocol. An author can even choose to adapt an existing virtual case, either from a colleague or in the public domain, and customize it to reflect the specific needs or objectives of his or her institution.

A Typical Simulation

Like any good story, a virtual case usually begins with an introduction of the characters, the situation, and the setting. For example, the learner may play the role of an ICU nurse caring for a patient presenting with advanced pneumonia. As the narrative evolves, ground rules are established and clinical data specific to the patient are requested and revealed, such as the patient’s medical history, a copy of a recent CT scan, results of the latest white blood cell count, and the dosage of antibiotic he is taking.

At this point, the learner is asked to make certain decisions about the patient’s care. This may include managing the amount of fluids the patient receives, determining the optimal dietary plan, responding to a sudden change in the patient’s heart rate, or deciding if a specialist is needed. Based on the responses received, future questions are generated specific to the demonstrated skill level of the user, becoming more complex if the appropriate course of treatment is selected or more remedial if mistakes are made.

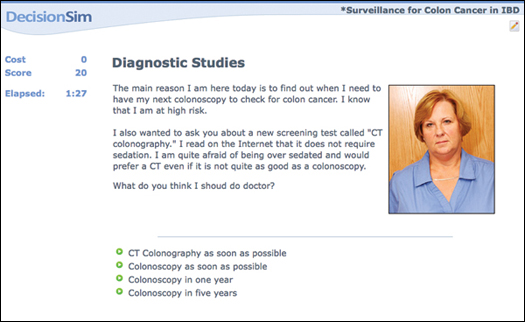

Figure 2. Virtual patient cases begin with an introduction including an overview of the patient’s symptoms and background along with choices for the learner to decide how best to proceed.

Along the way, adaptive feedback, including numerically-based scores and comments from the case author, are provided in real-time. Responses may be given immediately following a selection or later in the case when a positive or negative outcome of an earlier decision is revealed. For example, the author may choose to correct a learner’s misdiagnosis right away or wait until the patient’s health status declines before suggesting the learner back up and try an alternative approach. The author may also choose to combine other performance metrics, such as time or money spent, with the numerical score to provide a more accurate portrayal of real-world decision-making.

At the end of the simulation, learners receive a summary of the case, learning objectives, decision points, numerical scores and the final case outcome. In some instances, the learner may also be referred to resources for additional education, such as an online teacher, journal article, or clinical guideline.

Authors can then access detailed reports describing each learner’s decisions. With this information, outcomes can be compared with those of fellow students or colleagues, giving organizations an unbiased view into current practice behavior and the clinical reasoning skills of its staff.

More Effective Learning

By harnessing the power of interactive storytelling, virtual patients can improve educational outcomes and promote smarter clinical decision making. The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) describes the educational value of virtual patients as “indisputable” (Cohen, 2006), and these platforms are quickly emerging as an essential component of effective healthcare education, training, and assessment.

A recent analysis of virtual patients observes that these simulations provide several educational advantages over real-life patient encounters (Tworek, 2010). These include offering greater consistency in the delivery of learning experiences and enabling learners, rather than patient availability, to drive educational programs.

Another review of medical simulation technologies from Medical Teacher (Issenberg et al., 2005) identified a list of features that best support effective learning, all of which can be achieved through the use of virtual patient platforms. These 10 principles are:

- Feedback: Understanding the results of one’s performance.

- Repetitive Practice: Engaging learners in recurring, deliberate practice sessions that afford the opportunity to fix mistakes, enhance performance, and demonstrate skills.

- Curriculum Integration: Incorporating medical simulation as part of a broader educational approach that includes patient care experience.

- Range of Difficulty Level: Practicing medical skills with different degrees of difficulty.

- Multiple Learning Strategies: Employing simulations in a variety of settings, including independent learning, lectures, tutorials, and small groups.

- Clinical Variation: Exploring an extensive range of patient problems and conditions.

- Controlled Experiment: Allowing learners to make, detect and correct care-related mistakes without adverse consequences.

- Individualized Learning: Fostering personalized educational experiences where learners can advance their own pace and take responsibility for their progress.

- Defined Outcomes/Benchmarks: Setting clear goals with measurable objectives.

- Simulator Validity: Approximating complex clinical situations and tasks in an authentic, realistic manner.

As more healthcare institutions adopt virtual patients, this list delivers a comprehensive guide to selecting a platform that facilitates a positive learning experience for providers at all levels of training. Once a platform is implemented, the effectiveness of the educational experience will also be determined in large part by the amount of time and effort the author devotes to building cases that successfully engage learners, challenge their clinical reasoning skills and communicate constructive feedback. By mastering these techniques, authors can realize the true value of the technology and maximize its impact.

Better Care

Aside from improving educational outcomes, virtual patients also provide an opportunity to enhance the quality and safety of the care patients receive. As hospital administrators and other healthcare leaders face increasing pressure to regularly assess the competency of their caregivers, virtual patient platforms provide quantifiable, objective data that can be used to evaluate skills, detect deviations from established guidelines, and pinpoint those in need of additional training.

Unlike other methods for assessing clinical competency, such as multiple choice tests, oral exams, or on-the-job observations, virtual patient platforms provide insight into exactly how a clinician is performing and identify specific areas for additional practice and improvement. As a result, the decision-making skills of the clinician are not only enhanced, but patients ultimately receive safer, more effective care that complies with evidence-based protocols and techniques.

Virtual patients also improve care by supporting more comprehensive continuing medical education programs that enable caregivers to practice the application of new or updated clinical knowledge, diagnostics, services, and therapeutics as well as identify target areas for further study. Cases can be assigned to either specific learners or groups of learners, and competency can be based on scores, outcomes, or time spent completing the exercise.

The Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA), for example, recently incorporated virtual patients into its national SimLEARN (Simulated Learning, Education and Research Network) program to further the advancement of simulation training and education. By adding a virtual patient platform to the tools available to medical professionals, users will be able to review and practice systems-based protocols while applying clinical reasoning skills to various medical scenarios. VHA ultimately selected a platform that will integrate with its talent management system so case completion data for each learner is available for reporting, review, and analysis.

Achieving integration between virtual patient platforms, existing learning management systems, and other eLearning technologies can significantly streamline workflow for administrative staff by eliminating the need to re-enter case results or toggle between multiple systems. Learners benefit as well by being able to access all education-related applications seamlessly.

Lastly, virtual patients can serve as an effective behavior modification tool. For example, as an increasing number of organizations implement technologies like EHRs, CPOE, and barcoded medication administration, virtual cases can help reinforce the benefits of these tools and the potential danger of utilizing manual workaround solutions. By moving beyond the rote memorization of skills, healthcare institutions can influence provider decisions in a way that positively impacts the delivery of care enterprise-wide.

Looking Ahead

Virtual patients enable healthcare providers to develop higher-level decision-making and reasoning skills by letting them explore different decision paths and then immediately observing the consequences of their decisions—without risk. Beyond the benefits of encouraging active and participatory learning, these platforms engage caregivers in deliberate practice within an environment that is safe, consistent, convenient, and individualized.

While patients may not be in short supply, situations with these patients where learners can practice trial and error choices on them are. However, virtual patient platforms provide a viable and sustainable way to train numerous clinicians and evaluate their performance, while also providing access to rarer cases or ones that may not be ordinarily seen on rotation. With more organizations embracing the virtual patient model, possible uses of these simulations are growing exponentially, giving providers a window into how the choices they make affect patients over the short and long term.

Although virtual patients will never take the place of real-life clinical encounters, these simulations provide a wealth of unique advantages that successfully empower learners—whether practicing physicians, nurses, residents, or students—to hone their skills across a wide variety of cases. When used as part of a broader learning methodology that includes traditional classroom instruction and real-world experience, virtual patients improve not only the educational outcomes of providers but the health outcomes of actual patients as well.

James B. McGee is chair of the scientific advisory board at Decision Simulation, a provider of web-based virtual patient platforms. He also serves as assistant dean for medical education technology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and as an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. McGee may be contacted at JBMcGee@DecisionSimulation.com.