Victim Advocate Serves the Community at Cleveland Clinic

Carr: Do you collect data about the incidents you respond to?

Withrow: I do track data on the number of victims served, as well as type of victimization and other demographics as required by my funding source, the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA). We have seen growth in numbers over the last 2.5 years since I started in this position, which indicates to me that the need continues to be present for this type of service.

Carr:How do victims find their way to you?

Withrow: The bulk of my referrals come from police officers who are out in the hospitals and on the main campus in downtown Cleveland on a daily basis. We also have officers in our regional hospitals throughout northeast Ohio. Our Cleveland Clinic police officers staff those facilities 24 hours a day. Most of my referrals come from officers responding to calls and requests for service. They might refer someone to me who is filing a police report or someone involved in an event to which the Cleveland Clinic’s crisis intervention team has responded.

However, I have seen an increase in the number of referrals coming from other sources, such as nurses, physicians, case managers, employee assistance, medical assistants, or even individuals referring themselves who have heard about the program over the last couple of years.

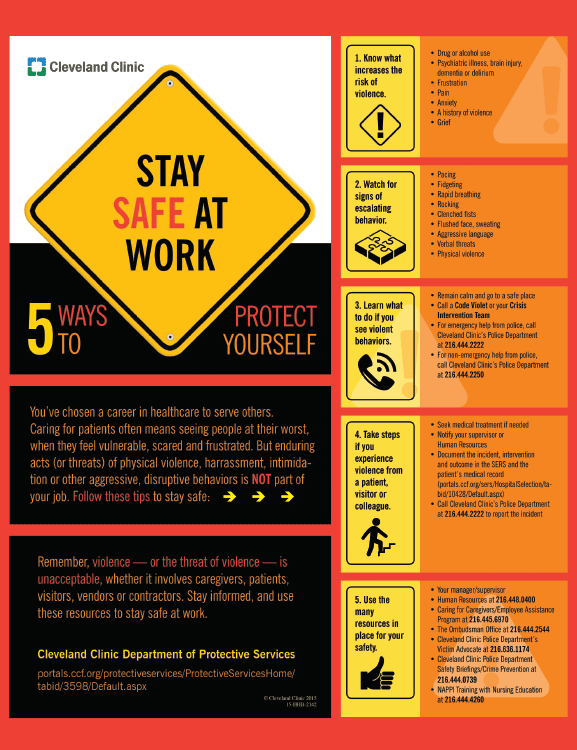

We hope we are creating awareness and a more victim-centered environment at the Cleveland Clinic. For example, we want to make sure our caregivers have the tools and resources they need to effectively screen patients for domestic violence. We also want caregivers to understand what workplace violence really is, and then know what to do should they feel they’ve experienced it. That’s another piece of what I do.

Carr: Given that it is unusual for a health system to provide this kind of support, are you aware of special commitment to this effort from leaders at Cleveland Clinic? How did this start, and where does the funding come from?

Withrow: In 2013, David Easthon, the chief of the Cleveland Clinic Police Department, became aware of funding through the Ohio Attorney General’s Office VOCA grant. Under his leadership, the Cleveland Clinic applied for and was granted funds for a full-time victim advocate position. VOCA funds were established in 1984 as a federal grant that takes fines and fees from convicted federal offenders and distributes the money to victim service providers across the country. We apply for continued grant funding each year.

Leadership has been important to my advocacy work as well as to our efforts to prevent workplace violence. In the case of employees who are victims of violence, the organization needs to provide support to the person who directly experienced the violence, as well as the entire department and unit where the incident occurred. The effects of violence can ripple across the team, and we must acknowledge and support each individual’s experience. Witnessing violence can cause psychological trauma, just like experiencing it directly. The message from leadership and managers following a violent incident must be clear and concise: “This was not your fault. This is not acceptable behavior. How can we help you feel safe?” I have seen many leaders come together to form a collaborative effort to address issues of workplace violence and other victim concerns in our healthcare system.

By helping patients, visitors, and employees of the Cleveland Clinic feel safe and supported through victim advocacy, we strive to improve the quality of services as a healthcare system and quality of life for those providing world-class healthcare.

Susan Carr is the former editor of Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare. She lives and works in Concord, Massachusetts, and may be contacted at susan_carr@mac.com.