Using Automated Surveillance to Improve Diagnosis

It’s even possible to reach those patients who aren’t active users of text messaging or email (and who also may be among those most likely to deteriorate clinically). Sometimes family members will respond on behalf of a loved one. In other cases, an automated surveillance system’s call-back module can be used to facilitate telephone contact with those who do not respond by email or text. This option quickly identifies those patients assigned more urgent emergency severity index levels, as well as those patients whose complaint might indicate the need for a call-back. For example, we would be more likely to check up on an abdominal pain patient who has not responded electronically as compared to a patient who presented for a simple suture removal.

Regardless of the method, electronic engagement not only aids in diagnosis, but can also give patients a voice by focusing on service as well as disease. For instance, even if a patient’s diagnosis is accurate and he or she feels better, an automated survey lets the patient provide feedback—positive or negative—about the service delivered by individual providers. By trending responses about the level of concern physicians demonstrate, ED leaders can identify outliers and develop service-training strategies to improve the patient experience.

Timing the communication

According to the IOM report, patients and their families are essential members of the diagnostic team. In fact, the report presents two checklists for patients to use to ensure thorough communication with their providers. These checklists, however, do not lend themselves well to emergent situations when patients do not have the opportunity to fully prepare for conversations with clinicians. For this reason, post-visit follow-up programs can play a vital role in extending those conversations.

Most EDs recognize the value of post-visit follow-up and call back those patients deemed most concerning. Still, the patients the call-back operators reach may be ill prepared for a conversation. With a provider waiting on the line, some patients may feel compelled to provide quick answers.

In contrast, the electronic survey system that we employ appears to mitigate some of those potential issues. Patients are able to answer the survey when it is convenient for them, and they can take their time providing more detailed feedback—feedback that may be of immense diagnostic value.

You check the tires—why not the patient?

Automated ED patient follow-up and car tires may not seem to have much in common. Yet, they actually do.

Think about the automated tire pressure monitoring system on today’s vehicles. The system diagnoses when a tire’s air pressure is low, often because of a minor issue or even a change in weather. However, that small indicator light also alerts the driver to an elevated level of risk. In fact, cars with underinflated tires are three times more likely to be involved in a crash, and they result in 120 preventable deaths annually (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration).

Digital well-being assessments offer a similar safety net. In our experience, the vast majority of discharged ED patients are feeling better at the point of follow-up contact. However, for the 2% who report feeling worse (Scaletta, 2014), the assessment serves as a technology-driven diagnostic aid.

In the U.S., there are 100 million ED discharges annually. If adopted nationally, automated post-discharge surveillance would generate several million next-day reports per year that identify patients who feel worse or are experiencing an aftercare issue. This enhanced communication might help avoid as many as 100,000 near misses and 10,000 adverse events annually. In keeping with the goals of the IOM report, tools like this can alert staff to a potential problem, help to avoid a misdiagnosis or make a treatment correction, and ultimately save lives.

Tom Scaletta is medical director of emergency services at Edward-Elmhurst Health in Naperville, Illinois. He may be contacted at TScaletta@edward.org.

References

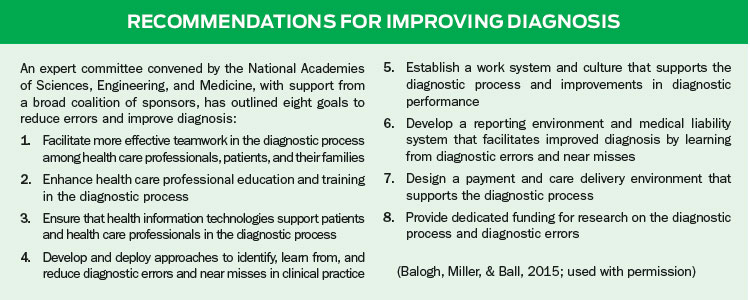

Balogh, E. P., Miller, B. T., & Ball, J. R. (Eds.). (2015). Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care

Brown, T. W., McCarthy, M. L., Kelen, G. D., & Levy, F. (2010). An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Academic Emergency Medicine, 17(5), 553–560.

Fast facts on US hospitals. (2014, January 2). Retrieved from http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts2014.shtml

FastStats – emergency department visits. (2015, March 29). Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 49 CFR Parts 571 and 585, RIN 2127-AJ23, federal motor vehicle safety standards; tire pressure monitoring systems; controls and displays. Retrieved from http://www.nhtsa.gov/cars/rules/rulings/tpmsfinalrule.6/tpmsfinalrule.6.html

Number, rate, and average length of stay for discharges. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/1general/2010gen1_agesexalos.pdf

Press Ganey Associates. (2010). Pulse Report 2010: Emergency department. Retrieved from http://helpandtraining.pressganey.com/Documents_secure/Pulse%20Reports/2010_ED_Pulse_Report.pdf

Scaletta, T. (2014, December). Automating patient contact after ED discharge enhances safety and reduces risk. Presented at the National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Orlando, FL. Retrieved from http://media.standardregister.com/standard-register/docs/Healthcare/T-Scaletta_2014_IHI_Storyboard.pdf