The Stories Behind the Data

November/December 2011

The Stories Behind the Data

Narratives in event reporting database reveal opportunities for fall prevention.

Patient falls continue to be one of the leading causes of adverse events and patient harm in hospitals (Dykes et al., 2010). Injuries from falls can increase the length of hospital stay and increase hospital costs (Dykes et al., 2010; Krauss et al., 2007). As a result, fall reduction and prevention has become the focus for many national and international organizations (Szumlas et al., 2004). For several years, The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals included fall reduction and prevention of harm from falls. Falls are also listed as 1 of 10 hospital acquired conditions (HAC) for which the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will lower payments or deny reimbursement based on fall severity, cost, volume, and whether falls are deemed preventable (CMS, 2010 October). Hospital Corporation of America Inc. (HCA), like many healthcare providers, has taken an aggressive approach to fall reduction, applying well-known best practice approaches for fall prevention. HCA hospitals and regions have achieved some impressive improvements, but have struggled with the same challenges to sustaining the improvements over the long-term that affect providers nationwide.

In 2008, HCA implemented an enterprise-wide voluntary event reporting system across its 164 hospitals as a cornerstone of the Patient Safety Improvement Program (PSIP). The PSIP database is comprised of de-identified close call and event reports from HCA facilities and is among the largest event repositories in the United States (Wu, 2011). Aggregated event data from HCA’s facilities allows the nature, frequency, severity, and contributory factors for each event to be collected, aggregated, and analyzed. Patterns not visible in smaller datasets emerge through the use of aggregated event reporting, offering additional insight into causation and contributory factors. High quality event analysis is a requisite part of engineering safe care because it allows effective risk reduction strategies to be identified and operationalized (Wu, 2011).

The study presented here used the HCA PSIP database to identify and analyze patterns to aid development of more sustainable falls prevention interventions. By looking beyond how the fall is coded within the database and studying the narrative accounts of the events, this study uncovered common themes and contributory factors that correlate to the severity of a fall. With this data, facilities may identify and adopt more sustainable falls prevention activities.

Methods

HCA is one of the nation’s largest healthcare delivery systems, providing approximately 5% of major hospital services in the United States through nearly 2 million inpatient visits and over 10 million outpatient visits per year. Currently, there are 164 HCA-affiliated hospitals, which include small, rural access facilities, general community hospitals, academic health centers, and large, tertiary-referral hospitals.

The PSIP Database

The PSIP reporting system was designed utilizing the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) Index for Categorizing Medication Errors in the classification of close calls and event severity (2001). Event data is voluntarily reported at each facility into a local database with key fields standardized to allow data transmission and aggregation. A monthly feed of the hospital data populates the PSIP database with de-identified event records, containing both the standard fields and the narrative description of the event. The aggregate data is then available for trending and analysis.

Analysis of Falls in the PSIP Database

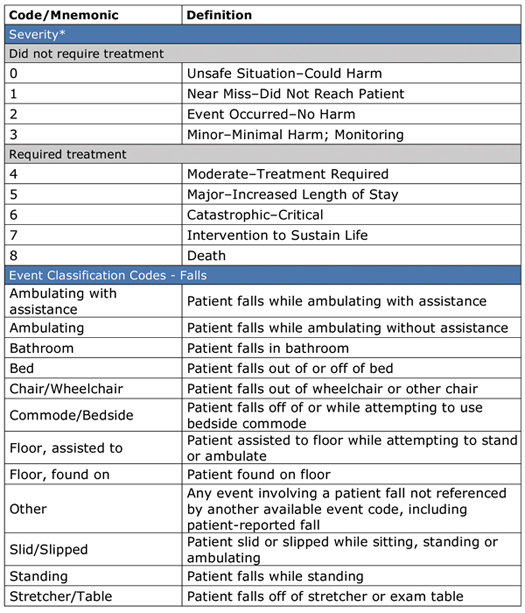

For this study, a fall was defined as an event involving a patient fall or slip that caused, contributed to, or had the potential to result in patient harm. Emphasis was placed on those falls which “required treatment,” defined as a fall event that is coded with a classification severity mnemonic code of 4 and above. Severity mnemonic codes and their definitions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. PSIP Database Fall Event Type Classification Codes and Definitions

*The PSIP severity classification codes were designed utilizing the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) standard taxonomy.

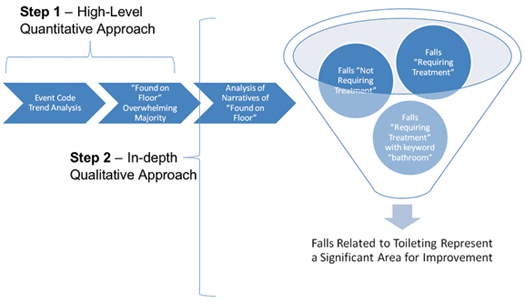

In the past, fall event data had been analyzed using the standardized fields, but this was one of the initial attempts to analyze the narrative accounts, listening for the voice of the direct care clinician to uncover additional insights into contributing factors for fall events. The data was analyzed in two ways, as presented in Figure 1. First, a high-level quantitative approach searched voluntary reports from 2010 for event type classification codes specific to falls. Event classification codes specific to falls are presented in Table 1. Events identified in this analysis were collated to identify significant percentages and/or trends and patterns from reports.

Figure 1. Methodology

Second, a qualitative approach used narratives to identify additional insights from the perspective of the staff members completing the reports, as codes alone typically do not reveal important contextual factors. For this approach, three different narrative samples, all coded as “Found on Floor” (the classification code that occurred most frequently), were analyzed: 1) a sample of 300 narratives from falls that “Required Treatment;” 2) 620 narratives from falls in the severity category of 4 and above (“Required Treatment”) and contained “Bathroom” as a keyword; 3) a sample of 300 narratives from falls that did not “Require Treatment.”

Results

Quantitative Results

During 2010, falls accounted for 14.4% of patient safety close calls and events that were voluntarily reported across all HCA hospitals. For all falls reported, 8.4% “required treatment” as defined in Figure 1. Additionally, in 2010, 13% of all patient safety events “requiring treatment” were falls.

Within the falls event type classification codes for 2010 (presented in Table 1), 49% of all falls were coded as “Found on Floor” and 14% were coded as “Bathroom” or “Bedside Commode.”

Qualitative (Narrative) Results

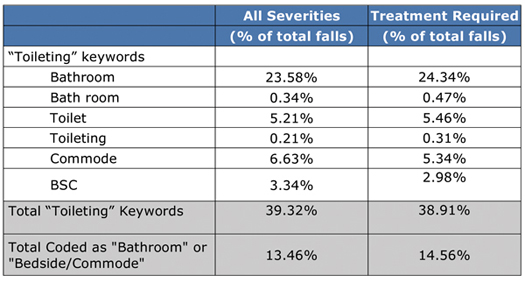

De-identified narrative data was analyzed from the three report samples (Figure 1). In addition, a keyword search of various terms related to “toileting” was performed in an effort to determine how many falls were related to toileting, regardless of event classification code. This inquiry revealed that 40% of falls were related to toileting, which stands in contrast to what a solely quantitative approach suggested with only 14% of fall reports coded as “Bathroom” or “Bedside Commode.” Table 2 (page 32) presents the toileting-related search terms used and frequency of those terms.

Table 2. Frequency of Falls Related to Toileting

The de-identified, aggregated narratives contained rich insights from the staff completing the reports that were not readily apparent when looking at the dataset solely based on event classification codes. After review, narrative findings were classified into one of four categories: staff responsiveness; toileting process failures; mechanical failures; and patient factors.

Staff Responsiveness

Two factors were identified in the narrative accounts that directly related to staff responsiveness. The first factor was the failure of a staff member to arrive in time to assist the patient who had called for assistance. The second factor was the failure of a staff member to recognize the need to go to a patient room either because the patient did not call for assistance or an alarm failed to signal the need for assistance.

Toileting Process Failures

A majority of factors related to the falls in this study were failures in the toileting process. Alterations in patients’ functional status (e.g., confused, dizzy, lightheaded, off-balance, etc.) when ambulating to the bathroom and/or once in bathroom were frequently described in the reports. It was also commonly reported that the patient had begun to toilet en route to the bathroom and then slipped and fell in his/her own waste. A third factor was the patient falling from the toilet when leaning over or getting up to clean themselves. Lastly, there were reports of patients slipping next to the bedside commode when attempting to use it without assistance.

Mechanical Failures

In this study, the most common mechanical failure noted was that the bed alarm was not working, and therefore the nurse was not notified when the patient got up and attempted to ambulate to the bathroom, resulting in a fall.

Patient Factors

There were reports of instances when the patient’s choices were a contributing factor to falls. For example, some reports indicated the patient used the call light, but did not wait for assistance. Other reports described patients who adhered to instructions to call for assistance for a period of time, then stopped calling for assistance because they felt it was no longer necessary. Some reports described patients failing to use the call light for reasons such as being embarrassed, feeling capable of handling the familiar task of toileting independently, and/or not wanting to bother the staff. Some reports indicated that patients were provided a bedside commode, but chose not to use it and fell going to the bathroom.

Additional Insights

Planning Failure: There were instances in which fall prevention interventions were not implemented until after a fall. In addition, there were a few situations in which the patient was not educated until post-fall not to get out of bed in an attempt to toilet without assistance. Both indicate that the patient may not have been determined to be at risk for a fall or there was a failure in the process of educating the patient.

Execution Failure: A few patients fell even with assistance (i.e. the patient suddenly blacked out or slipped en route while being assisted by a staff member).

Discussion

A qualitative analysis of narrative data was particularly valuable as the narratives represent the voice of the frontline clinician and provide an opportunity to identify specific contributing factors or circumstances associated with events. It is important to note that the findings from this study are based on voluntarily reported event data and are not intended to be a rate-based metric finding. Utilizing a qualitative approach allowed information regarding care processes, settings, and context to emerge from the dataset, providing insight that was not available when looking solely at quantitative event report data.

The narrative summaries provide valuable insights for interdisciplinary fall teams working to prevent patient falls and falls with injuries. Fall prevention efforts focused on toileting represent a significant area for developing sustainable prevention activities that reduce the overall number of falls and create an environment that prevents harm caused from falls. Three key areas for improvement were identified: staff responsiveness, equipment, and patient engagement. It will be important for a team of nurses and design experts to review the data and present solutions as well as engage patients in order to define safe toileting practices that patients find understandable and acceptable.

These reports indicate a need to redefine the traditional toileting process. Diminishing variability in staff response time to patient calls may be an effective harm-prevention strategy, especially for patient calls associated with the need to toilet. Findings from the narrative report review revealed that in many cases falls still occurred even when interventions such as a low bed, no-slip socks, signage, and a bed alarm were in place for patients identified as at risk to fall. A redesign of fall prevention systems may be more effective if focus is placed on design of particular activities in which all patients are at greater risk. This might include new toileting parameters, such as the attendant no longer leaving a patient alone in the bathroom and/or the attendant handing the patient toilet paper rather than requiring the patient to reach for it. A key element to consider in the redesign process is the cognitive status of the patient. Different toileting processes should be considered for patients who are cognitively impaired versus those who are not. A simple assessment may be used to check for cognitive impairment (e.g., can the patient follow directions?) (Harlein et al., 2010).

A careful reading of analysis emerging from narrative reports reveals patterns that may lead to redesign of patient rooms and bathrooms to reduce the risk of falls associated with toileting. This includes redesign that lessens the use of bedside commodes, minimizes the distance from the bed to the bathroom, and ensures the path to the bathroom is clear of any obtrusive objects that may hinder the patient’s ability to easily ambulate to the toilet. It could also include redesigning bathroom doors to minimize the risk of entanglement or entrapment. The placement of toilet flushing devices and toilet paper holders could be rethought to reduce patient movements that could lead to a fall.

Conclusions

The study revealed that the use of voluntarily reported data might be misleading if viewed solely from a quantitative perspective. Classification coding and trending based on event type alone do not reveal the complexity behind fall events. Narrative data provided by first responders and direct care clinicians contain rich insights that can help focus prevention efforts along a more sustainable path for preventing falls, especially those that result in patient harm. In this analysis, fall prevention efforts that are focused on toileting represent a significant opportunity for reducing the overall number of falls and for creating an environment that prevents harm caused from falls.

At the time the article was written, the authors worked in the Clinical Services Group at Hospital Corporation of America Inc. (HCA) in Nashville, Tennessee.

Margaret Jones is an administrative resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and worked at HCA while completing her MBA.

Kathryn Mitchell is the manager of patient safety at HCA and may be contacted at Kathryn.Mitchell@hcahealthcare.com.

Barbara Olson is the director of patient safety at HCA and may be contacted at Barbara.Olson@hcahealthcare.com.

Jason Hickok is the assistant vice president of patient safety and infection prevention at HCA and may be contacted at Jason.Hickok@hcahealthcare.com.

Jane Englebright is the chief nursing officer, patient safety officer and vice president at HCA and may be contacted at Jane.Englebright@hcahealthcare.com.

Table 1. PSIP Database Fall Event Type Classification Codes and Definitions

Figure 1. Methodology

Table 2. Frequency of Falls Related to Toileting