The Right Approach for the Right Result

Applying Lean Leadership to Achieve Standard Work in IV Therapy

By Lee Steere, RN, CRNI, VA-BC

Introduction

Over the past decade, hospitals have shifted their care delivery focus from quantity to quality, a direct result of the value-based purchasing programs introduced as part of the Affordable Care Act. Using financial incentives, these programs encourage hospitals to improve quality, efficiency, patient experience, and safety of care.

Yet improving the quality of care cannot be done without addressing the issue of waste, which is endemic in healthcare, as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) notes in its Call to Action for health system leaders. Waste must be proactively identified and eliminated to achieve the IHI’s Triple Aim, a framework to assist health systems in improving patient care and outcomes while reducing healthcare costs.

Perhaps one of the clearest examples of waste in hospitals today is also one of the most widely performed procedures—the insertion and maintenance of peripheral IV catheters (PIVC). So in 2015, Hartford Hospital’s vascular access specialty team (VAST) embarked on a quality improvement initiative to transform our facility’s infusion therapy practices. The initiative was inspired by a hospitalwide effort to eliminate waste and improve safety, as well as a commitment to uphold the core values of the Hartford HealthCare System: caring, safety, excellence, and integrity.

As our experience shows, standardizing PIVC insertion practices can help an organization achieve the Triple Aim by improving patient safety and satisfaction, while significantly decreasing hospital costs. More than five years after beginning this journey, we are sharing our experience as a road map for other facilities looking to improve their processes and quality of care for a procedure that impacts nearly every patient in the hospital.

PIVC: Waste, variability, and defects

As the most commonly performed invasive procedure in all of healthcare, approximately 90% of hospitalized patients receive a PIVC at some point during their stay, and the majority receive more than one. In fact, 350 million catheters are sold in the United States each year, a number that exceeds the total U.S. population.

Lack of training is a major contributing factor to the waste, variability, and defects that plague this routine procedure. Nursing students receive little to no training on appropriate PIVC selection criteria or insertion techniques. This leads to variable work processes that result in multiple insertion attempts and high failure rates. On average, the number of PIVC insertion attempts is 2.18 to 2.35 catheters per placement (Keleekai et al., 2016). Even after successful PIVC placement, it is estimated that approximately 50% of catheters fail because of preventable complications and must be replaced (Helm et al., 2015).

This explains why patients fear needles more than prognosis, according to a recent survey of hospitalized patients (Sweeney, 2016). The end result is patient dissatisfaction, potentially harmful adverse events, use of more invasive vascular access devices (VAD), and increased healthcare costs.

At Hartford (Connecticut) Hospital, an 867-bed acute care teaching hospital, we believed PIVCs could be inserted more effectively and efficiently using a Lean-based approach. We set out to develop a standard work process that applies best-practice approaches to reduce needlesticks and prevent premature catheter failure. The key to this process transformation was centralizing PIVC insertions within a team of experts who specialize in IV therapy—the VAST—using an evidence-based care model to reduce waste and variability.

A successful change in culture is a delicate equation that requires the right approach to get the right result. This approach includes a sufficient number of staff members who are properly trained in IV therapy; standard work processes, including bundled best practices and technology; and a high level of collaboration between frontline clinicians and nursing leadership who share the same vision.

The journey begins: Collecting the data

Anchoring change in an organization’s culture requires support from the top down. To get behind any kind of process transformation, hospital leadership will need metrics to prove that the proposed change will translate to better clinical outcomes and patient care.

The first step is collecting and presenting key data on the current state of PIVC insertion practices to establish baseline measures. In 2015, the VAST started the process by assessing our annual catheter and IV supply consumption. Based on hospital admission and supplies data, we calculated an average of 4.4 catheters were consumed per patient visit. Our team also developed a cost analysis to establish the cost basis per bed for IV therapy—a large cost that is widely unknown to hospital administrators. At an average cost of $28 per PIVC insertion, we estimated an annual cost of $4.1 million ($4,781 per bed) for PIVC insertions, which includes both supplies and nursing time.

Next, the VAST set about creating the vision for the ideal future state that would reduce variability and eliminate waste. We sought to increase PIVC dwell times while reducing adverse outcomes, with the ultimate goal of achieving 1 PIVC per patient stay (Gorski et al., 2016). Using principles of LEAN/Six Sigma methodology, we designed an evidence-based best-practice framework—called the PIV5Rights™ bundle—to address the most common reasons for PIVC failure: infiltrations, phlebitis, infection, occlusion, and accidental dislodgement.

A key element of the PIV5Rights bundle is having PIVC insertions performed by a dedicated VAST. IV insertion is both an art and a science, and we felt strongly that placing the procedure in the hands of specialists who have a thorough understanding of vascular access issues and their impact on patient safety would improve outcomes and lead to better patient care (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The PIV5Rights Bundle

To collect the data, we designed a prospective, comparative multi-modal study that compared PIVC insertions by the VAST using the best-practice bundle to a generalist clinician using the standard-of-care process. The goal of the study was to show better patient outcomes, fewer IV-related complications, and overall cost savings by achieving 1 PIVC per patient stay with the PIV5Rights bundle.

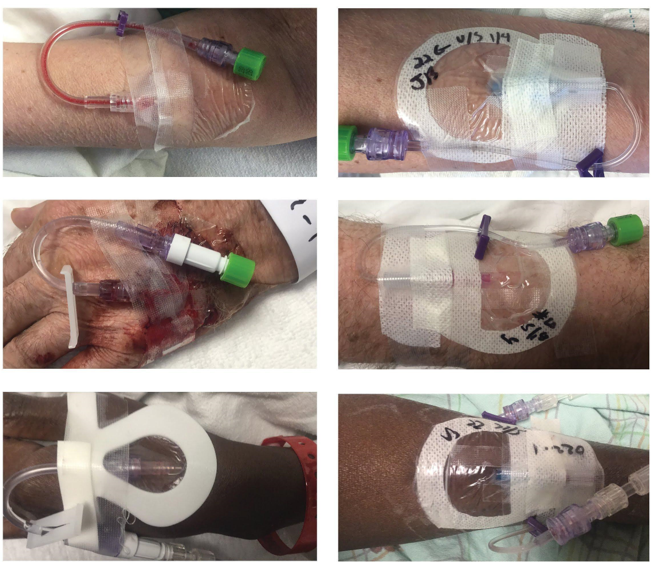

The study included specific elements that would demonstrate the clinical and financial benefits of the bundled VAST approach, including photo documentation and standardized data collection and analysis. The VAST took photos during every assessment of every PIVC in the study to provide a side-by-side comparison between the two approaches (Figure 2). In addition, the team developed a HIPAA-compliant iPad® app used to uniformly collect data about PIVCs, and all study team personnel were trained on its functionality.

Figure 2

After obtaining IRB approval, the VAST conducted the study in a 47-bed medical unit from November 2016 to February 2018. The study included 125 patients with a total of 207 PIVCs. The data collected were validated and analyzed by a senior research scientist for the hospital. While we expected to see positive outcomes with the PIV5Rights best-practice model, the actual results far exceeded even our most optimistic expectations.

Phase 2: Presenting the data

Published in the Journal for the Association of Vascular Access, our study found that the PIV5Rights standard work process was associated with higher insertion success, longer dwell times with fewer complications, greater patient satisfaction, and significantly reduced IV therapy costs (Steere et al., 2019).

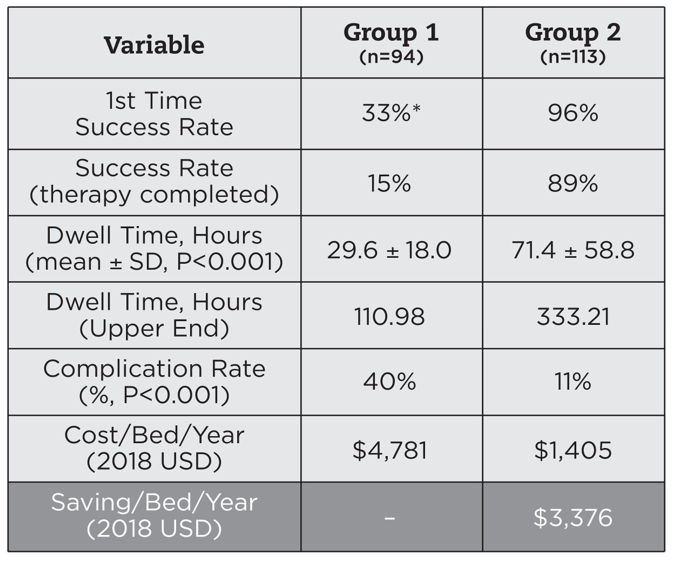

Using the best-practice bundle, the VAST successfully inserted 96% of PIVCs on the first attempt, and 89% of the catheters lasted until the end of treatment. In contrast, only 15% of catheters inserted with the generalist model lasted until therapy completion. In addition, the PIV5Rights approach led to fewer harmful complications, reducing the complication rate from 40% with the control group to just 11% with the VAST.

Overall, the standard work model reduced Hartford Hospital’s projected catheter consumption by 90%, which translates to a projected annual savings of $3,376 per bed, or $2.9 million overall. This includes both direct and indirect cost savings due to the reduction in IV supplies as well as nurse training and labor costs. Fewer central line–associated bloodstream infections, fewer treatment interruptions, and higher patient satisfaction scores may further increase the financial impact of this new model by contributing additional savings and/or increased reimbursement (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Overall results

Based on these results, and the powerful clinical and economic benefits we were able to demonstrate, hospital leadership approved the proposal to centralize PIVC insertions within the VAST in late 2018.

Though we were already more than three years into the process, the real work was only just beginning. Now we faced the challenge of expanding the VAST and training the team members in the standard work processes in order to begin implementing this evidence-based approach throughout the entire hospital.

Phase 3: Building and training the team

Between selecting and training the right candidates, we knew the journey wouldn’t yield results overnight. After all, we weren’t only attempting to build a team; we were also trying to change the culture of an entire organization.

When this process started in 2015, our VAST consisted of seven RNs and two LPNs, equating to roughly seven full-time employees. In less than four years, the size of our team increased nearly threefold to 23 RNs (an equivalent of 20 FTEs) without adding to the hospital’s overall FTE headcount. As our analysis showed, implementation of the PIV5Rights model could save more than 37,000 hours of nursing time spent on PIVC insertions. This enabled us to reallocate full-time nursing staff from other departments to the VAST, while giving the floor nurses more time to focus on patient care and other quality improvement initiatives.

Choosing the right people meant not only focusing on their vascular access skills, but also their personality and how they would interact with the rest of the team. A standard workflow requires every team member to be on the same page, executing the process in the exact same way, every single day. Clinical skills, while important, can be taught over time; a “team player” mentality cannot.

Once the right people are selected, training them is a long, ongoing process. We averaged a minimum of four to six weeks of training per new team member. As a small department, we faced the added challenge of having a limited number of available preceptors to facilitate training at any given time. Our orientation focused on theory-based concepts to get the new team members up and running, knowing we could focus on refining the standard work process at a later time.

In July 2019, more than four years into the process, the VAST took over all PIVC insertions in the hospital’s inpatient units, with the exception of labor & delivery and critical care units.

Phase 4: Hardwiring the standard work process

After onboarding was complete, we could finally shift our focus to hardwiring the standard work process to better manage workflow. Essentially, this process provides the VAST members with a script to follow throughout their daily routine, and our standardized data forms enable uniform collection and reporting of critical information about every PIVC. Every morning at 7 a.m., the entire VAST assembles in a morning huddle, facilitating a successful handoff and ensuring that every team member is following the appropriate process.

The VAST is divided into four teams across the hospital. The teams proactively round on all new admits from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., with the goal of having all patients assessed within 24 hours of admission. This early assessment ensures that every patient receives the most appropriate VAD. Our team is able to perform a daily review of all central lines for necessity, while increasing the use of midlines when appropriate.

As the months went by, we began to see a significant decrease in the amount of IV site requests. Instead of always racing to catch up, the proactive rounding and early assessment as part of the standard work process enables our team to stay ahead of the requests.

We’re seeing positive results on the other end as well, including an increase in patient satisfaction scores. Based on over 3,000 surveys, our average Press Ganey score increased by five points, from 68% at baseline to 73% after centralizing PIVC insertions within the VAST. These improved patient satisfaction scores are moving us closer to achieving the Hartford HealthCare balanced scorecard initiative of 75.6%.

With patient satisfaction potentially linked to millions of dollars in reimbursement funds, this improvement can have a significant financial impact on the hospital. In addition, the VAST model increased our billable IV services from $6 million to $7.4 million. With the VAST’s proactive approach to PIVC placement, we’ve been able to decrease the number of unsuccessful insertion attempts while increasing billable IV services.

In recognition of this significant effort, the VAST was named Hartford Hospital’s 2019 Clinical Team of the Year. Selected from a group of 27 teams by a committee made up of local community leaders, this award honored the team’s innovative approach to improving IV care at the bedside (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Looking ahead: Standard work observations and tracking real-time outcomes

Though we experienced some disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the VAST members picked right up where they left off when normal hospital operations began to resume in May 2020. This is a testament to the power of the standard work process and how ingrained it has become for every single team member. As we continue to move forward, the next step is to begin standard work observations to ensure adherence to the PIV5Rights care model, which requires hiring a clinical nurse leader to assist with observations. This will enable us to identify and address any issues as soon as they arise and hopefully minimize their impact.

The last step will be implementing a system to track productivity and outcomes in real time. In addition, we’re also considering putting the VAST under the auspices of a medical director so we can increase oversight and track better quality data, as well as increase revenue.

The future of IV therapy for Hartford HealthCare and beyond

Currently, we’re helping other hospitals within the Hartford HealthCare network to facilitate the same process transformation. By working with one facility at a time to implement the PIV5Rights evidence-based care model, our eventual goal is to standardize how infusion therapy is managed across the Hartford HealthCare system.

As our experience shows, an effective quality improvement initiative requires significant time and effort. The right approach requires choosing the right team members, the ability to foster teamwork, and a mindset of continuous improvement, as well as the support of hospital leaders who share the same vision.

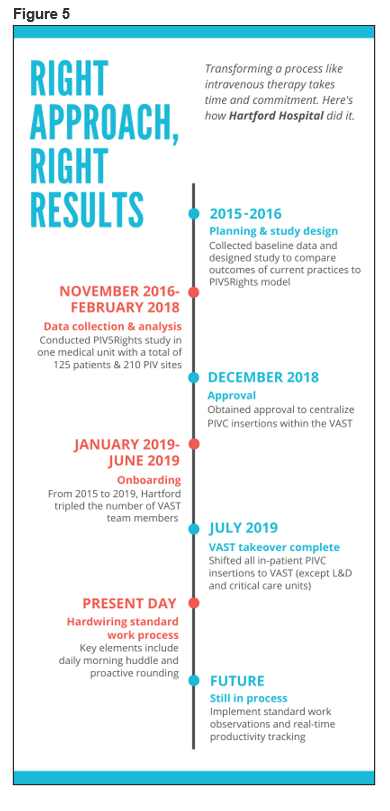

Was the reward worth the challenge? Absolutely. For an invasive procedure that affects nearly every single patient in the hospital, the journey to getting the right result is most certainly one worth taking (Figure 5).

Lee Steere, RN, CRNI, VA-BC, is the unit leader of IV therapy services at Hartford Hospital. He also chairs the Hartford HealthCare’s Clinical Value Team and is a member of their HAI Committee.

References

Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M., McGoldrick, M., Orr, M., & Doellman, D. (2016). 2016 infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 39(1 Suppl.), S1–S159.

Helm, R. E., Klausner, J. D., Klemperer, J. D., Flint, L. M., & Huang, E. (2015). Accepted but unacceptable: Peripheral IV catheter failure. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 38(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/nan.0000000000000100

Keleekai, N. L., Schuster, C. A., Murray, C. L., King, M. A., Stahl, B. R., Labrozzi, L. J., Gallucci, S., LeClair, M. W., & Glover, K. R. (2016). Improving nurses’ peripheral intravenous catheter insertion knowledge, confidence, and skills using a simulation-based blended learning program: A randomized trial. Simulation in Healthcare, 11(6), 376–384.

Steere, L., Ficara, C., Davis, M., & Moureau, N. (2019). Reaching one peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) per patient visit with lean multimodal strategy: The PIV5Rights™ bundle. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access, 24(3), 31–43.

Sweeney, C. (2016). The patient empathy project: Dealing with patient fears improves experience. Network News [online]. Hartford HealthCare. https://hartfordhealthcare.org/file%20library/publications/network%20news/networknews-feb-2016.pdf