Technology & Quality: Usable Evidence-Based Guidelines… for Real

January / February 2005

Technology & Quality

Usable Evidence-Based Guidelines… for Real

![]()

For more than two decades, clinicians struggled to use evidence-based guidelines. Ever since Wennberg’s work back in the 1970s demonstrating the huge practice variation seen even in relatively small geographic areas, quality experts have worked to promote guideline use among physicians to ensure that interventions on patients actually did them some good.

Throughout the 1980s, managed care organizations did everything possible to get physicians to use guidelines in an effort to enhance quality and control costs. Their efforts included education, guidelines distribution, economic incentives, and patient education.

Unfortunately, the evidence on guideline use shows poor acceptance. In addition, numerous experts state that it takes up to 17 years for a new, effective treatment procedure to be widely adopted. This may be an exaggeration, but surely it takes longer than required. In the meantime, patients receive inappropriate, unhelpful, or even harmful care while valuable resources are wasted.

Difficult to Remain Up-to-Date

To be fair, the rapid advancement of medicine makes it nearly impossible for any physician to remain completely up-to-date on clinical progress. Also, with such rapid change, it is difficult for physicians to separate the valuable information from the less valuable or even suspect medical knowledge that deserves little attention. Lastly, the format that medical information normally comes in — journal articles and medical reports — is in the wrong information format to be integrated into a typical medical practice. For example, it requires a huge effort for a physician to evaluate a single peer-reviewed article on a specific aspect of a disease process, and then apply that single bit of knowledge to a small subset of patients within a practice panel.

All clinicians at one time or another have worked on guideline development. Their experiences have probably been similar: about 80% to 90% of the guideline is developed rather quickly, while the remaining portion is labored over for weeks, months, or even years. Often the guidelines are never completed or, if completed and disseminated, rarely used. We all know that it is easy to develop guidelines, but very hard to develop high-quality, respected, and most importantly, usable ones. In addition, upkeep of the guidelines usually never gets done.

With the advent of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and high-capacity personal digital assistants (PDAs), there is technology that can effectively deliver guidelines (See References). A new Web technology standard, the InfoButton, offers access to context-sensitive help within clinical applications, a very effective and useful way to deliver clinical content at the point of care. The challenge exists to develop high-quality, effective, and easy-to-use guidelines that can be deployed intelligently, consistent with workflow, and at the point of care.

Clinical Evidence

Through an effort begun in 1995 by the United Kingdom’s National Health Service and the British Medical Journal (BMJ) Publishing Group, there now exists a “formulary” of evidence-based medical knowledge. The current iteration of the guidelines, named Clinical Evidence (www.clinicalevidence.com), covers over 180 clinical conditions and evaluates over 2,148 treatments. Major disease categories covered are listed in Figure 1.

|

Clinical Evidence is available in two print versions, full and concise. The release of each version is staggered so that any changes in the guidelines can be included in the next version. It is also available online via a Web-based interface (www.clinicalevidence.org), as well as through a synchronized PDA device.

Guidelines are updated continuously with full literature searches in each topic every 12 months. As new information becomes available, it is incorporated into the Web-based version of Clinical Evidence and subsequently the next print version.

Driven by Clinical Questions

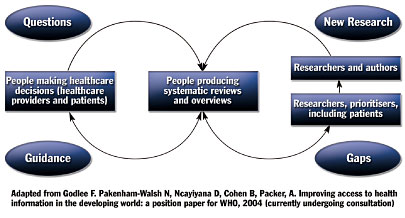

Unlike most guidelines, which are driven by clinical research, Clinical Evidence is driven by clinical questions. The literature review and other research done by the guideline developers works to answer clinical questions through presentation of medical knowledge in a format that is easy to understand, access, and use. As can be seen in Figure 2, clinical questions identify gaps in knowledge that lead to research, dissemination of knowledge to clinicians, use of that knowledge by clinicians, and identification of additional gaps in the knowledge that lead to questions and further research.

![]()

This methodology fosters guidelines that are clear, easy to read, and simple to apply. Additionally, the creators clearly dedicated much thought to how the clinical information is conveyed in the guidelines, continually tweaking it to make it better and more valuable to clinicians.

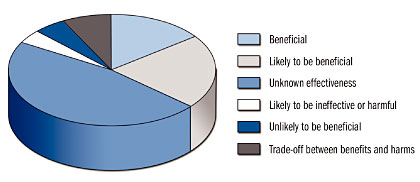

Each guideline evaluates treatments and places them in one of six descriptive areas ranging from “beneficial” to “unlikely to be beneficial.” Of 2,148 treatments in the current printed issue (June 2004), 329 (15%) are rated as beneficial, 457 (21%) likely to be beneficial, 164 (8%) as trade-off between benefits and harms, 106 (5%) unlikely to be beneficial, 94 (4%) likely to be ineffective or harmful, and 998 (47%) as unknown effectiveness (Figure 3).

![]()

The evaluative categories for treatments are defined as follows:

- Beneficial: Effectiveness has been demonstrated by clear evidence from RCTs (randomized clinical trials); expectation of harms is small compared with the benefits.

- Likely to be beneficial: Effectiveness is less well established than for those listed under “beneficial.”

- Trade-off between benefits and harms: Clinicians and patients should weigh up the beneficial and harmful effects according to individual circumstances and priorities.

- Unknown effectiveness: There are currently insufficient data or data of inadequate quality.

- Unlikely to be beneficial: Lack of effectiveness is less well established than for those listed under “likely to be ineffective or harmful.”

- Likely to be ineffective or harmful: Ineffectiveness or harmfulness has been demonstrated by clear evidence.

Focus on Outcomes that Matter

Clinical Evidence focuses on outcomes that matter to the patient and the physician such as severity of illness, quality of life, disability, and survival. Guidelines include a list of outcomes and how they are measured. Proxy outcomes such as decreased lipid levels or blood pressure are of lesser interest to the researchers as they are less clear on their true impact on the individual.

Guideline developers mainly utilize the Cochrane Library, Medline, and Embase, looking for high-quality reviews of RCTs. The evidence is then summarized and peer-reviewed by the section advisors, at least two external expert clinicians, and by an editorial committee that includes both expert clinicians and epidemiologists. A standardized process allows for collection of comments by Clinical Evidence users.

Through the generous support of the United Healthcare Foundation, Clinical Evidence is available free to all physicians in the United States. Additionally, through other supporting organizations, it is free to physicians in England, Wales, Italy, and developing countries. It regularly is translated into French, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, and German.

Slawson et. al stated in an article published in 1994 that the usefulness of information is equal to its relevance, multiplied by its validity, divided by the work required to extract the information. With Clinical Evidence and its implementation through features such as InfoButton, guidelines, and clinical information technology, developers seem to finally be offering truly valuable and impactful tools that can greatly reduce practice variation, employ best practices, and improve care.

References

Chaiken, B. P. (2001). Evidence-based medicine: A tool at the point of care. Nursing Economics 19(5), 234-235.

Chaiken, B. P. (2002). Clinical decision support: Success through smart deployment. Journal of Quality Health Care 1(4),15-16.

Chaiken, B. P. (2002, October 11). Opinion: Clinical guidelines at point of care needed to improve quality, safety. iHealthbeat, California Healthcare Foundation, www.ihealthbeat.org.

Godlee, F., et. al. (2004, June). Clinical evidence concise, Issue 11, June BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. (Godlee is the executive editor, as there are over 50 editors and advisors)

Slawson, D. C., Shaughnessy, A. F., & Bennett, J. H. (1994). Becoming a medical information master: Feeling good about not knowing everything. Journal of Family Practice38, 505-513.

www.micromedex.com, InfoButton Access, Thomson Micromedex.