Technology – Getting to the Recall on Time: Improve Safety with Automated Recall Management

May / June 2005

Technology

Getting to the Recall on Time: Improve Safety with Automated Recall Management

For several months in late 2001, The Johns Hopkins Hospital unknowingly used a defective bronchoscope that resulted in 2 deaths and 400 injuries. A manufacturer’s letter that would have alerted Hopkins officials and physicians to the danger was mailed to the same place the devices were shipped: the loading dock.

This incident and the normal, cumbersome process for getting recall alerts and pulling defective materials off the shelves caused the Hopkins patient safety committee to question whether there was a better way.

The Tip of the Iceberg

The bronchoscope incident led Hopkins to recognize the significant deficiencies in the way alerts were being managed, most of which came from a lack of readily available information. A number of studies were conducted that provided insight into the volume of alerts that need to be managed on a regular basis — and the answer was hundreds, if not thousands. Added to the problem is that alerts come from numerous sources and in many different forms. Hopkins really needed a better way to analyze, sort, and manage this information.

Alerts were also taking a long time to move through the management stages from the time the alert was received at the hospital before all the appropriate actions were completed and the alert could be closed.

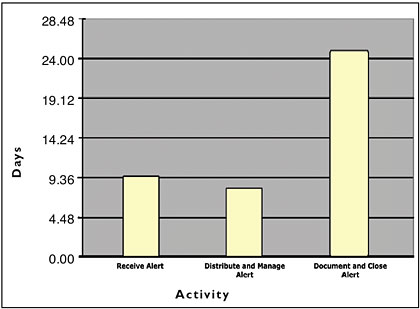

Hopkins noted that on average it took 9.36 days for the hospital to receive an alert from the manufacturer. Figure 1 illustrates the additional 8.41 days required to distribute and manage the alert. This meant that under current manual processes, Hopkins patients were exposed to potentially harmful products for more than 17.77 days. Hopkins then averaged 24 more days to document and close the alert. The cumulative days from when the alert was released by the manufacturer until the alert was closed was an astounding 41.77 days!

![]()

Automating the Process

An alert management system, implemented at Hopkins, uses knowledge management technology coupled with clinical experts to scour a multitude of worldwide sources of alert information. The staff, with the aid of the tool’s parsing and duplicate detection features, separate the alerts by category — medications, devices, materials, blood, food (14 domains in all), type, and urgency. The staff also adds additional information that may be of value to the subscribers. For example, if the alert is related to a previously released alert (i.e., an expanded recall) or is an update to a previously released alert, the staff will indicate that information in the comments section. In addition, contact information to discuss the alert with the manufacturer is also provided when available. The alert is then released to the subscriber community.

Subscribers, having defined the persons in their organization responsible for those types of products, receive the alerts pertinent to them for review and action. So now rather than searching through a stack of alerts for all types of products, the staff receive the alerts they are responsible for managing, i.e., pharmacy receive the pharmacy alerts, clinical engineering receive the biomedical alerts, etc. The staff then assigns the alert to staff to locate the product and remove from the shelves or service. All actions taken by the staff are captured with the alert including when they have viewed the alert, any notes they have entered, and when the alert has been closed. The system monitors for timeliness and notifies staff and management when alerts are not being managed within the timeframes set by the organization. This feature ensures alerts are not missed, set aside, or just not managed in the tightest timeframe possible.

Benefits:

Safer Patients, Visitors, and Staff

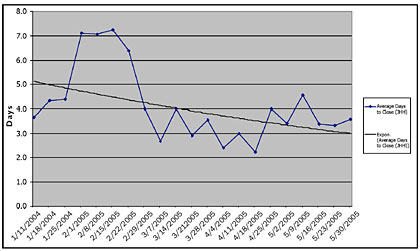

The most sought-after outcome was realized almost immediately after implementing the system. Hopkins now has an average alert life cycle of approximately 3.6 days or less (Figure 2). As a result, the window of “potential patient exposure days” has closed dramatically. When products are removed from stock and devices are removed from service faster, this risk for negative consequences for the users or potential recipients of those items also decreases.

![]()

In addition, Hopkins expanded the boundaries of alert management to include alerts that not only were patient-centric in nature, but those that could harm even visitors or staff, such as food and facilities alerts. The realization that a number of items used by staff (e.g. ovens in the staff lounges) or that could be used for visitors (e.g. automatic external defibrillators hanging in hallways) needed to be included in comprehensive recall management was a wakeup call to expand alert management beyond the JCAHO Environment of Care Standards.

Time Equals Money

One of the most positive benefits realized by the Hopkins staff was that staff no longer had to look for the alerts or analyze them to determine if they were new or a duplicate of the same alert but from an additional source. The elimination of the paper processes and faxing alerts to various individuals in the organization has been a true timesaver. By setting up the appropriate filters provided by the tool, the need to wade through documents such as the FDA Enforcement report on a weekly basis has been eliminated. The result has been a 67% decrease in the volume of alerts with an 80% reduction in time required to spend managing alerts.

Visibility by Department or Organization

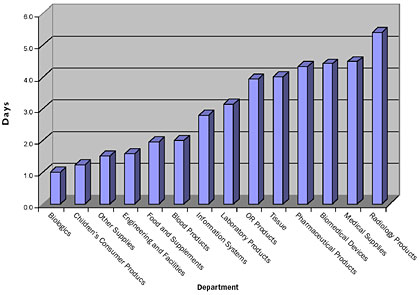

Decreased “at risk” days, although clearly the most important outcome of all measurement criteria, is not the only benefit achieved to date. The system has allowed Hopkins to examine the management process in detail and to then develop new processes that provide both increased efficiency as well as providing visibility within the organization.

The availability of reports that clearly identify which departments are requiring longer timeframes to complete all required actions has allowed Hopkins to focus its attentions and address issues as they relate to a specific department. This data was previously only available through experiential comments.

Delay-and-Escalationn and Management Oversight

Many alerts are not actual product recalls but are notices such as “field corrections” or notices to educate staff about appropriate use of a product. For these circumstances, the tool provides a feature to adjust delay-and-escalation timeframes on a recall-by-recall basis by staff with the appropriate authority for this type of change. This serves two purposes: first, the adjustment cannot be overused, and second, the system manager is kept informed of what actions are ongoing within the facility.

There is now the ability for administration (risk management, patient safety, and legal) to maintain insight into the process and to step in when needed. The “nag notices” allow management early follow-up warning if someone is out sick or failed to transfer their alerts before going on vacation. If the escalation notice jumps to their level, they now place a quick phone call to those involved to determine what further follow-up is required.

Simplified Audits

Hopkins is not immune to tests of internal process by organizations such as the FDA and JCAHO. In the past, audits by these organizations for alert management required someone to search through a filing cabinet looking for the specific alert requested. This often took several days before the appropriate documentation could be recovered, especially if all confirmations of action were not received.

Using automated alert management, an alert can be found within 1 minute from any computer in the hospital with Internet access. A clear audit trail of actions can be demonstrated via the workflow record. This has also proven to be an excellent source of information to monitor and demonstrate our actions for internal review — and without the heartburn.

Identifying Whether a Defective Device Has Been Recalled

On occasion, Hopkins utilizes the system to determine whether a manufacturer or the FDA has actually released a recall. For example, Hopkins identified a defective device via a “Dear Doctor” notice that was sent to one of our clinicians. This was not a formal recall but indicated that one might be forthcoming. After a search was conducted on the manufacturer’s and FDA Web sites and a discussion with the vendor representative confirmed that a recall notice would be forthcoming, we scanned and submitted the Dear Doctor notice into the system and utilized the normal process to ensure that we had completed all actions. Out of interest, we monitored the FDA and manufacturer to see when the recall notice would be issued. We were surprised to discover that it was not released until 8 weeks later. Consider the number of patients that we had ensured were not affected by the defective product through having a system that allowed us to take proactive actions.

Similarly a syringe recall was recently completed by Hopkins staff. A few weeks later the “same” syringe was still causing problems. The first question from administration was “Why is the product still on the shelves when it was already recalled?” Within 2 minutes we had our answer. By searching in the system and comparing that recall notice to the syringe packaging, it was identified that the defective product was not of the same batch that was recalled. This enabled Hopkins to proactively contact the manufacturer and make them aware that they needed to expand their recall. Alert management staff were comforted by the assurance that they could rapidly demonstrate that they had, in fact, taken all appropriate actions for the previous recall and they had identified the new issue.

Submitting Recall Notices

The ability to submit manufacturer notices directly into the system has ensured that all actions and records are maintained in a single system. When other institutions submit alerts that they’ve received when they receive them, all subscribers become immediately aware of the alert — potentially weeks before they receive their own recall notice, if it gets to them at all. One company, for example, recently alerted a Hopkins otolaryngologist about a problem with a product. The physician immediately sent the letter to the risk management office. The alert was uploaded through the service thus becoming immediately available to Hopkins and all other subscribing hospitals to manage accordingly. The recall didn’t appear on the FDA’s enforcement report until two months later. This feature, had it existed at the time of the bronchoscope recall, may have served to minimize what turned out to be a disastrous outcome for both the patients and for Johns Hopkins.

![]()

To further reduce the risk of this type of incident from occurring, Hopkins instituted a policy that all new contracts with product manufacturers requires them to send recall notices directly to the risk management office for submission to the service.

Summary

Over the past 2 years, Johns Hopkins has been involved in the development, testing, and implementation of this new Web-based system for the collection, distribution, and management of alerts and recalls for defective products. With the Hopkins Hospital as the lead, we’ve successfully rolled the service out to all of the hospitals, clinics, and outpatient centers in our system. We believe we have achieved significant improvements in terms of ensuring capture of alert notices, as well as reducing our administrative burden associated with management of this process. We continue to refine our processes through the use of reports and tools such as escalation process and the ability to create our own alert notices. We have seen dramatic reductions in the time that it takes us to complete all required actions. However the most satisfying aspect to the introduction of the system is that we have clearly demonstrated dramatic improvements in the quality of care that we provide our patients by ensuring that they are not exposed to defective products. We have learned from the experience of trying to manage the defective and missed bronchoscope alert, and we will now do everything in our power to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

Peter Pronovost is the medical director of the Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care and an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology/Critical Care Medicine at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine. Pronovost’s special interest is applying clinical research methods that improve quality of healthcare and safety. Within the Johns Hopkins community he co-chairs the Patient Safety Committee and serves on the Johns Hopkins Health System’s Performance Improvement Council and Leadership Development Program, and is core faculty for the Program for Medical Technology and Practice Assessment. On a national level, Dr. Pronovost is an active member of the National Coalition on Health Care and is the medical advisor for the Leapfrog Group for patient safety.