Suicide Prevention Outside the Psychiatry Department

September / October 2009

Suicide Prevention Outside the Psychiatry Department: A Bundled Approach

With the advent of The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) and the Institute of Medicine’s report To Err Is Human (IOM, 2000), patient safety has returned to the forefront in healthcare. Meanwhile, across the nation, the network of inpatient psychiatric facilities is shrinking. The number of persons struggling with mental health conditions, however, is not, and their demands on the acute healthcare system are growing.

Suicide ranks as the eleventh most frequent cause of death in the United States, as reported in Screening for Mental Health Resource Guide (2007). Although there are no official statistics on attempted suicide, i.e., non-fatal actions, The American Association of Suicidology estimates there are 25 attempts for each death by suicide (2005). Patient suicide, while in a staffed, round-the-clock care setting, has been the second most frequently reported type of sentinel event since the inception of The Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Policy in 1996 (TJC, 2008). Furthermore, The Joint Commission found of inpatient suicides that occurred in general hospitals it studied over a 2-year period, 44% of these patient suicides occurred in medical/surgical areas (TJC, 1998).

Many patients who have failed at their attempt to commit suicide are admitted from a hospital’s emergency department to an intensive care unit for further medical stabilization, and are later transferred to a behavioral care unit for psychiatric care. Potential perils exist during the transition phases of a suicidal patient’s care. While the process has been assumed safe, emergency and intensive care nurses and physicians are often inexperienced in psychiatric assessment and treatment.

To provide safe passage for at-risk patients from the point of hospital entry to the behavioral unit, a bundled approach was utilized to develop a suicide prevention care pathway. Patient assessment, consultation and collaboration, environmental safety, and patient/family education are key components of the risk reduction strategy. This focus on suicide prevention during the pre-psychiatric unit admission phase is designed to enhance safety for at-risk patients.

A Community Hospital’s Reality

Catawba Valley Medical Center, the 32nd Magnet Hospital in the Nation, is located in a rural community in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. It is a not-for-profit, 258-bed acute care facility with a psychiatric services department that, during fiscal year 2006/2007, provided care to 1,347 patients of various acuity levels. During this time, 539 of those patients were admitted to the Medical Center following a suicide attempt or the expression of suicidal ideations. Because a patient’s medical condition immediately following a failed suicide attempt can be of primary concern, depending on the degree of self-inflicted harm, immediate placement on the psychiatric unit is often not appropriate. Such was the case for 10% of these 539 patients dictating admission to non-psychiatric units where the care environment is far less safe for someone who has intentionally acted to harm themselves.

Psychiatric patients are admitted through the emergency department (ED) to only two areas of the Medical Center, the critical care unit (CCU) for treatment and medical stabilization or the psychiatric department. The challenge we faced was to provide safe and appropriate patient care in the non-psychiatric areas, just as the psychiatry department provides. With wall-mounted, potentially dangerous equipment and supplies kept in virtually every room in the ED and CCU, evaluation of the environment and subsequent alteration are paramount. Moreover, in early 2007, a patient eloped from our CCU. This event elucidated the need to focus on the failed suicide-attempt population in a more introspective way. It became readily apparent that a means to guide care and promote safety for suicidal patients, while being treated by clinicians who do not normally manage psychiatric situations, was needed.

A Bundled Approach to Suicide Prevention and Treatment

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement introduced the bundle concept for the 5 Million Lives Campaign. Carol Haraden, PhD, IHI vice president and patient safety expert, has clarified the bundle definition. “A bundle is a structured way of improving the processes of care and patient outcomes: a small, straightforward set of practices—generally three to five—that when performed collectively and reliably, have been proven to improve patient outcomes.” (IHI, 2006). Care providers know that the intervention package, or bundle, must be executed for every patient, 100% of the time, according to Haraden (IHI 2006); therein is the key to a bundle’s success. Simultaneous implementation of the group of interventions produces better outcomes, according to Litch (2007). In the case of suicide prevention outside the psychiatry department, our bundled approach utilized best practice evidence (Level I evidence was not available) for the design of a risk reduction care pathway with the expectation that all elements would be followed by direct care providers for every at-risk patient. The risk reduction tool would not only guide practitioner thinking, but could also form the basis for a measurable decrease in the potential risk for patients to inflict self harm.

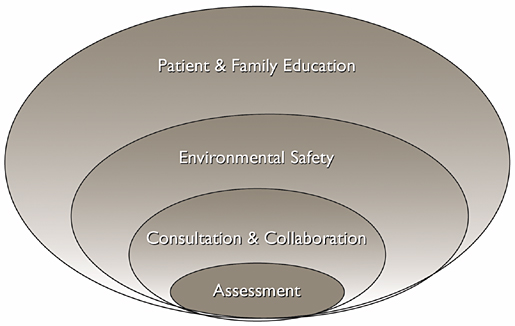

Initially, a failure mode effects and criticality analysis (FMECA) was conducted by a multidisciplinary team. Safety and treatment concerns for the suicidal patient in non-psychiatric areas areas were thereby identified, evaluated, and prioritized. The therapeutic milieu was dissected and each aspect considered in detail. Collaboratively, multiple disciplines, as well as several specialties within nursing, worked through the many possible scenarios that could arise with suicidal patients. The care pathway that emerged includes four component categories: assessment, environmental safety, consultation and collaboration, and education for the patient and family (Figure 1). Our bundled approach to suicide prevention will be discussed in terms of creating safe environments and providing safe passage concomitantly with appropriate treatment for at-risk patients being treated outside the psychiatry department.

Figure 1: Elements of the Suicide Prevention Care Pathway

Safe Passage in the Emergency Department

Like most hospitals, the ED is the “front-door” of our organization, and the location of many psychiatric patients’ first encounters. Early in the initial triage process, a psychiatric resource nurse (PRN) is notified that a patient has presented in the ED who requires their expertise. Generally, before the triage process has concluded, the PRN arrives to aid in the assessment, planning, and treatment of the patient.

The suicidal patient is placed in a “safe room,” which is a normal ED treatment room until a patient presents who may be a danger to themselves. The room’s sink and cabinet are the only permanently attached fixtures. The sink has been boxed in to eliminate access to the plumbing, and the cabinet tops have been sloped and rounded to lessen the risk of self-harm. To facilitate patient observation, the safe room door has a window equipped with external blinds for use when privacy is required. When a suicidal patient presents to the ED, this room’s normal equipment, which is housed on a movable cart, is removed. Either a mattress is placed on the floor or a single chair is provided to the patient after the stretcher is removed. Room activity is monitored by video surveillance. The patient’s clothing and/or belongings are collected and examined for objects that could be used to inflect self harm. The patient and/or family members are educated throughout the process.

The PRN assists the emergency nurse with patient assessment and, when appropriate, facilitates the inpatient stay at the Medical Center, or transfer to another acute care psychiatric facility. For those psychiatric patients who are to be discharged from the ED, the psychiatric resource nurse makes referrals to appropriate community-based services that will adequately meet the patient’s needs. As the content expert, the PRN often fills a consultative role with the primary provider. In certain instances, the PRN may have knowledge about the patient from a previous visit or other information that is invaluable relative to diagnosis and treatment. Routine nursing assessment of suicidal ideation, plans, or gestures is conducted at least every 12 hours and as needed. Level I precautions are warranted when the patient has recently attempted suicide by a lethal method, e.g. hanging, potentially lethal drug overdose, etc., has clear intent to follow through with a plan or is delusional. In these cases, the emergency nurse observes the patient at a minimum of 15-minutes intervals.

Transfer from the ED to the inpatient psychiatric unit or the CCU is potentially one of the most dangerous times for the patient and other persons in the ED and/or along the transport route. This phase of transition between “safe” environments requires cooperation between the PRN, hospital police when appropriate, and the ED staff. The emergency nurse escorting the patient from the ED has possession of the patient’s belongings. Upon arrival to the psychiatric unit an environment specifically designed for safety and care of the suicidal patient has been achieved. For those patients who are medically unstable following a suicide attempt, the CCU is the inpatient admission unit. The same care is taken for patient transport to CCU.

Safe Passage in the Critical Care Unit

During the CCU phase of medical instability, the care focus is life preservation and hemodynamic stability. These are care areas in which the critical care nurse has expertise. A critically ill patient who has survived an attempted suicide is not at risk of self harm while in this acute phase; they are unable to act on self-harm intentions. While the patient’s medical criticality is very high, their psychological criticality is low.

However, when the patient regains consciousness and/or is extubated and realizes their attempt was unsuccessful, their risk for self harm may return. If the patient does exhibit self-harm risk, it may likely be severe. At this point, the patient’s medical criticality diminishes and his or her psychological criticality increases substantially. The care focus shifts from life preservation to self-harm prevention. The former is well within the CCU nurse’s comfort zone, while the later often is not. Moreover, traditional CCU patients whose conditions are no longer medically critical generally require less monitoring and observation. Such is not the case for the medically stable, failed suicide-attempt patient. In our experience, it was found that CCU nurses needed additional education about this highly volatile phase. They also needed support from colleagues trained in the psychiatric discipline to appropriately address and care for the patient’s emotional needs during their CCU stay.

What is imperative for maintaining the safe passage of failed suicide-attempt patients while in the critical care unit? As is the case in the ED, environmental safety is a primary concern. A suicidal patient is admitted to a CCU video-monitored room, from which all potentially harmful items have been removed, regardless of his/her medical stability status. The room is under constant surveillance by the monitor technician and/or nursing staff. The patient is dressed in a hospital gown without strings, and the bed exit alarm must be engaged at all times while the patient is in bed. Patient clothing and belongings are examined for potentially harmful objects and personal items are sent home with a family member or stored in a secure locker. Education and instructions are concomitantly provided to the patient and/or family regarding the safety measures being taken. Dietary Services is informed that patient meals must be delivered on disposable trays with plastic utensils; no cans or glass are allowed.

The CCU nurse consults the psychiatric resource nurse upon a failed-suicide attempt patient’s admission to the unit to assist in patient care and environmental safety assessment. The PRN works collaboratively with the critical care nurse to identify the patient’s level of suicide risk, design their care and plan eventual transfer to the psychiatric unit. Patients assessed as medically stable and physically able to act on suicidal intent are placed on Level I precautions, which require the CCU nurse or nurse aide to observe patient behavior at least every 15 minutes and document their findings. For patients who are identified to be at a high level of risk, the PRN expedites a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner consult and subsequent transfer to the psychiatry department. The PRN rounds in the CCU every 12 hours until the patient is discharged or transferred. Additionally, the PRN is notified upon extubation, with increased level of consciousness, and/or when the patient is able to act on suicidal intentions.

Tremendous value has been found in this collaborative approach between the psychiatric expert nurse and the critical care expert nurse in providing appropriate medical and psychiatric patient care simultaneously. Safe passage between the CCU and the psychiatric department presents many of the same challenges as described for transition between the emergency and psychiatry departments, thus requiring similar precautions and preparations.

Elements of the Suicide Prevention Care Pathway

As depicted in Figure 1 (see page 35), there are four major elements to our bundled approach to suicide prevention in non-psychiatric areas at Catawba Valley Medical Center. Indeed, each piece holds independent value and significance. However, when taken collectively the overall value of the care pathway increases dramatically. The task of providing safe passage and appropriate treatment for at-risk patients requires interaction of the elements at multiple stages in their hospitalization.

Assessment. Psychiatric resource nurses are available at the hospital 24/7. These specially trained nurses are immediately contacted when an at-risk patient presents to the ED. They may assist the provider in making admission decisions. If admission is recommended for the patient, be it at this facility or elsewhere in the area, PRNs facilitate these efforts, as they are current on bed availability both inside and outside this facility. Ongoing patient assessment must be conducted by both emergency and critical care nurses during a patient’s stay in their respective departments. Every 12 hours, the PRNs round in the ED and CCU providing appropriate psychiatric assessment for suicide risk patients.

Consultation /Collaboration. Patient assessment guides decision-making with respect to assigning the level of precautions that will ensure appropriate patient care. Again, this is an ongoing process of collaboration between non-psychiatric and psychiatric practitioners. Each clinician contributes based on his or her particular skill set and area of expertise. The support offered by PRNs for emergency and critical care nurses, in this less familiar genre of care, augments the patient’s care.

Environmental Safety. This element addresses the physical environment of the patient’s room as well as his/her person and belongings. Family and visitors are also considered with regard to the patient’s environmental safety in terms of items they may possess that the patient could use to inflict self harm.

Patient/Family Education. To reduce anxiety levels for both patients and their families, nurses provide information regarding the safety measures implemented in each specific care area. Family members are educated about the purpose of the precautions and their own role in the patient’s safety. The education is generally verbal in the ED, whereas in the CCU and psychiatry department it is both verbal and in the form of a comprehensive brochure. Compliance with the intended safety measures is often dependent on the degree to which everyone involved understands the measures and the rationale behind them. As should be the case in any patient assessment, the family and the family dynamics are key when dealing with this at-risk patient population. A well-informed, involved family can be a valuable tool in assuring safety for failed-suicide attempt patients.

Summary

Self-harm incidents and suicide attempts are not completely uncommon in the hospital setting. Healthcare organizations and/or individual clinicians should not be lulled into complacency simply because inpatient suicides may be infrequent. Lack of frequency is not synonymous with lack of possibility; inpatients can and do commit suicide. If such risks are actualized, the events could be devastating for an individual patient or for multiple patients, visitors, property, and staff. Thus, it is crucial that precautions be in place to ensure patient and general safety. The acutely ill, psychiatric patient population is not decreasing, neither are their presentations to emergency departments. It is vital that, immediately upon their presentation, organizations are prepared to provide appropriate treatment in environments that are safe and appropriately therapeutic. Equally important is safe passage from the ED to the intensive care/inpatient unit on to the psychiatric unit and back to the community. Non-psychiatric environments are replete with environmental hazards for suicidal patients, and direct care providers in these areas can experience inadequacies in addressing the myriad needs of these patients.

The suicide prevention care pathway described herein is a proactive risk reduction strategy that seeks to ensure the safety of suicidal patients being treated in areas outside the inpatient psychiatry department. Since its implementation, the bundled approach has bolstered consistency of practice and the standardization of treatments and environmental considerations for the intended population in our emergency and critical care service areas. This initiative has improved sensitivity in both CCU and ED nurses who provide care to emotionally ill patients. Currently, compliance with bundle protocols is being measured in both non-psychiatric areas of our facility, while potential inpatient suicide attempts and patient elopements continue to be tracked.

In closing, NPSGs 15 and 15a mandate that hospitals “identify safety risks inherent in its patient population” and “identify patients at risk for suicide” respectively (TJC, 2008). However, The Joint Commission does not provide specific guidelines for operationalizing the intent of these goals. Nonetheless, it is incumbent upon healthcare providers to ensure that current practice and treatment environments are evaluated and deemed safe and appropriate for patients at risk for suicide in all areas of the hospital, especially non-psychiatric areas, e.g. emergency, intensive care, etc. Our suicide prevention care pathway focuses attention on improved patient care for this acutely vulnerable population.

Susan Bumgarner graduated as a diploma nurse in1978, and then earned a BSN in 1985 from Lenoir Rhyne College in Hickory, North Carolina. She completed her MSN at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in1996. She holds national certifications as an advanced nurse executive (NEA-BC) and in medical/surgical nursing (RN-BC). Bumgarner’s extensive clinical background includes work at the bedside in multiple clinical venues. She was formerly the organizational director of clinical education at Catawba Valley Medical Center where she currently serves as nurse administrator for adult medical surgical services. Bumgarner is a Magnet appraiser for the American Nurses Credentialing Center.

Van Haygood earned a BSN from the University of South Carolina, in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1993 and an MS in nursing management and leadership from Walden University in Baltimore, Maryland. Haygood holds national certification, through the American Nurses Credentialing Center, as a nursing executive (NE-BC). He has held staff nursing and leadership roles in multiple patient care areas including critical care, cardiovascular surgical recovery, and telemetry. Haygood’s passion and specific area of expertise is emergency nursing. He currently serves as administrator of emergency, post-procedural care, and direct admission services for Catawba Valley Medical Center. Haygood may be contacted at vhaygood@catawbavalleymc.org.

Resources

Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2008, 5 Million Lives Campaign. “Getting Started Kit: Prevent Central Line Infections How-to Guide.” Available at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/CentralLineInfection.htm

Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2008, 5 Million Lives Campaign. “Getting Started Kit: Prevent Surgical Site Infections How-to Guide.” Available at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/SSI.htm

Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2008, 5 Million Lives Campaign. “Getting Started Kit: Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia How-to Guide.” Available at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/VAP.htm

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank

- The CVMC Suicide Prevention Team

- Greg Billings, RN-BC, Administrator, Psychiatry Services

- Tracy Hancock, RN, BSN, CEN, Nurse Manager, Emergency Services

- Kimberly Yates, MSN/MHA, RN-BC, Nurse Manager, Psychiatry

- Beth Rudisill, RN-BC, MSN, Clinical Development Coordinator, Psychiatry Services

- Miriam Jolly, RN, BSN, CPAN, CNA-BC, Director, Professional Nursing Practice

- Bonita Hefner, RN, MSN, CPAN, NE-BC, Clinical Development Coordinator, Medical Unit

- Crystal Shepherd, BA, RN, PCCN, Patient Care Coordinator, Critical Care

- Kenny Whiteside, RN, BSN

- Mike Helton, RN, CVMC Nursing Informatics

- The CCU, ED, and Psychiatry nursing staff members

The authors also wish to express their appreciation to Rebecca Creech Tart, PhD, Director for Research and Evidence-Based Practice at Catawba Valley Medical Center, for editorial assistance.

References

American Association of Suicidology (AAS). (2005). U.S.A. suicide: 2005 official data. Retrieved November 2, 2007 from http://www.suicidology.org/associations/1045/files/2005datapgs.pdf

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). (2006, September 7). What is a Bundle? Retrieved April 10, 2008 from http://64.29.219.190/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/WhatIsaBundle.htm

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. L. T. Kohn, J. M. Corrigan, & M. S. Donaldson (Eds.), Washington, D.C.:National Academy Press.

Litch, B. (2007). How the use of bundles improves reliability, quality and safety. Healthcare Executive, March/April, 13-16.

Patient suicide: complying with national patient safety goal 15A. The Joint Commission Perspectives on Patient Safety. February, 2008:7-8.

Screening for Mental Health. (2007). A Resource Guide for Implementing the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations 2007 Patient Safety Goals on Suicide. D. Jacobs (Ed.), Wellesley Hills, MA: Screening for Mental Health, Inc.

The Joint Commission (TJC). (2008). 2008 National Patient Safety Goals Hospital Program. Retrieved March 14, 2008, from http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/08_hap_npsgs.htm

The Joint Commission (TJC). (1998). Inpatient suicides: recommendations for prevention. Retrieved July 7, 2008, from http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_7.htm

The Joint Commission (TJC). (2008). Sentinel Event Statistics. Retrieved September 15, 2008, from http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/Statistics