Strategies for Delivering LGBT-Inclusive Care

The diverse individuals of the LGBT community share a “common need for culturally competent health care” that recognizes and responds to population-specific medical risks (Health Resources and Services Administration, n.d.). The learning curve to understand these distinctions—and how they can impact a patient’s health status and clinical presentation—may appear steep to providers who do not have expertise addressing gender identity and sexual orientation; however, there are several recommended strategies and many educational resources to help providers deliver LGBT-inclusive care.

The Joint Commission (2011) describes the LGBT population as an “overlooked community” of healthcare consumers disproportionately affected by health disparities. The accrediting agency’s patient-centered communication standards include provisions to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression. Consistent with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Conditions of Participation, The Joint Commission also requires facilities to protect patients’ rights to choose who may visit them during an inpatient stay regardless of whether the visitor is a family member, same-sex spouse or partner, or other type of visitor.

Section 1557 of PPACA prohibits healthcare providers that receive federal funds from discriminating against patients based on race, national origin, sex, age, or disability. In a final rule published on May 18, 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) definitively established that sex discrimination includes discrimination based on gender identity and sex stereotyping. Although the final rule does not resolve whether discrimination on the basis of an individual’s sexual orientation alone constitutes sex discrimination under Section 1557, HHS states that the agency will continue to follow legal developments in this area and “supports prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination as a matter of policy.” Additionally, the final rule states that the HHS Office for Civil Rights will evaluate allegations of sex discrimination on the basis of an individual’s sexual orientation to determine whether they involve the sorts of stereotyping that can be addressed under Section 1557 (Nondiscrimination in health programs and activities, 2016).

LGBT advocacy groups have also played a major role in setting the agenda for LGBT-inclusive healthcare. For example, the Human Rights Campaign Foundation (2016) publishes data on organizational commitment to LGBT patients and staff in its annual Healthcare Equality Index (HEI) report. To earn leadership status, organizations must have the following core criteria in place:

1.Patient nondiscrimination policies with specific references to sexual orientation and gender identity

2.Equal visitation policies

3.Employment nondiscrimination policies with specific references to sexual orientation and gender identity

4.Staff training in LGBT patient-centered care

Of the 568 facilities completing the 2016 HEI survey, 496 were designated as leaders in LGBT equality, meaning that a minority—fewer than 10%—of approximately 5,900 U.S. hospitals achieved this designation. Survey participation is voluntary and does not reflect the efforts of other healthcare facilities to provide LGBT-inclusive services. The 2016 HEI report compares the results of participating healthcare facilities to findings for more than 900 other “nonrespondent” hospitals whose policies were publicly available. Many of these organizations, which represent the majority of U.S. hospitals, fell significantly short in meeting the core criteria for LGBT inclusion (Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 2016).

Health disparities

Research indicates that LGBT individuals experience the following mental and physical health disparities, as well as disparities in access to care:

- Lesbian women are less likely to get preventive cancer screenings. Lesbian and bisexual women are more likely to be overweight or obese (Daniel & Butkus, 2015).

- Gay men are at higher risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (Daniel & Butkus, 2015).

- LGBT individuals have higher rates of smoking, alcohol use, and drug use, and are 2.5 times as likely to have a mental health disorder as heterosexual men and women (Daniel & Butkus, 2015).

- Transgender individuals have a higher lifetime risk for suicide attempts (Daniel & Butkus, 2015).

- LGBT adults and their children are more likely to be uninsured and face difficulties gaining access to care (Daniel & Butkus, 2015).

- LGBT survivors of intimate partner violence face additional challenges, including fear of discrimination, being blamed for the abuse, and involuntary dis

closure of sexual orientation (Dunne, 2014).

closure of sexual orientation (Dunne, 2014).

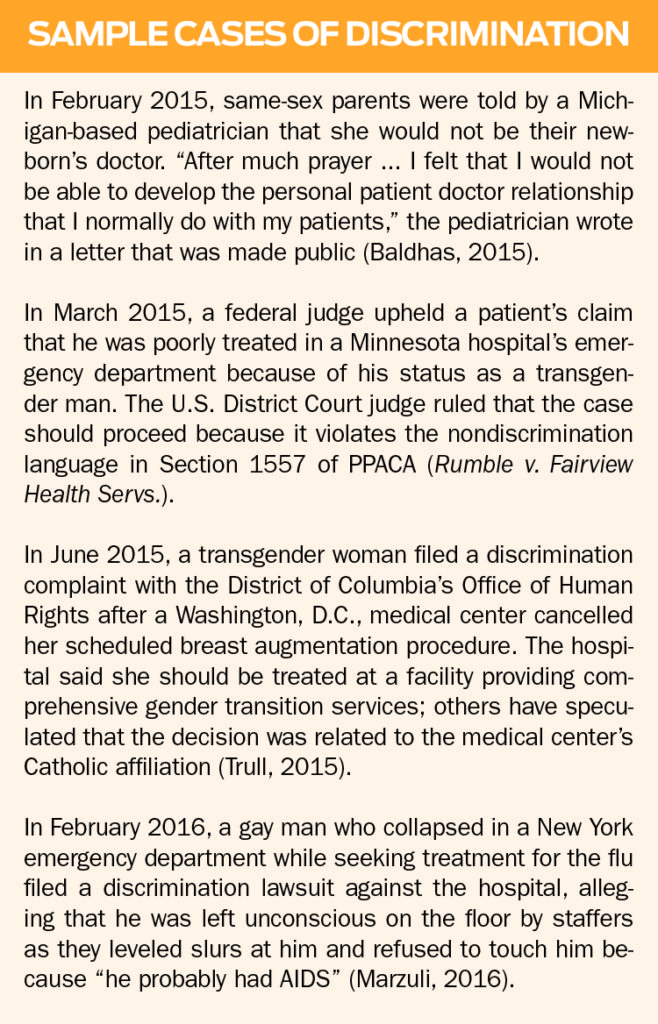

LGBT individuals also report discrimination when seeking healthcare. In a 2009 survey conducted by Lambda Legal, a civil rights organization for LGBT persons, about 56% of nearly 5,000 lesbian, gay, or bisexual respondents reported experiencing at least one instance of discrimination (i.e., healthcare professionals refused to provide care, blamed them for their health status, refused to touch them, used harsh or abusive language, or were physically rough or abusive). Rates were higher for transgender and gender-nonconforming respondents and for individuals living with HIV (Lambda Legal, 2010).

More recently, the Human Rights Commission Foundation (2016) reported examples of discrimination including physician’s office staff directing a transgender female patient to a restroom at a nearby fast food restaurant rather than the women’s room in the office’s waiting area, a provider who persisted in calling a transgender man “she” despite his repeated corrections, and an emergency department physician who wanted to do a genital exam on a transgender woman seeking care for a broken rib; when she refused, the physician refused to treat her.

Such discrimination, while often quietly pervasive, is also increasingly being made public; see “Sample Cases” for details. Although high-profile cases in which LGBT patients are refused care may help spark necessary changes in patients’ treatment, they may also make individuals reluctant to seek care in the future, even when life-saving treatment is indicated.

Assessment

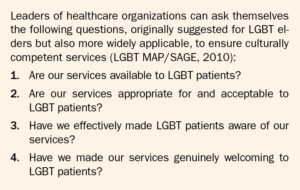

Leaders can assess their organization’s risk exposure in serving the LGBT community by evaluating existing practices. Some have found that the questions posed in the HEI application provide a good framework for inclusion initiatives. The 2016 HEI survey consists of 43 questions about LGBT care practices. Seven of those questions cover the four core criteria that determine HEI leadership status; the rest address best practices for LGBT-inclusive approaches, such as identifying LGBT-knowledgeable providers and designating a contact for LGBT-related matters (see Resource List for the HEI report, an interactive map, and resources for policy development).

Another useful tool to evaluate how well an organization serves its LGBT population is The Joint Commission’s report, Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community (2011), commonly referred to as the “field guide” (see Resource List).

Success story

The end result of LGBT-inclusive approaches is not only the delivery of appropriate care, but also improved patient and family satisfaction. For example, in anticipation of the emergency admission of an adolescent transgender female requiring treatment for severe testicular pain, leaders of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center transgender clinic informed the providers who would be treating the patient of the patient’s transgender status and told them the patient’s preferred name and pronoun. Everyone was prepared by the time the child arrived, and the respectful treatment brought the entire family relief even before surgery (ECRI Institute, 2015).

Strategies

Providers and organizations can take the following steps to increase personal and professional preparedness to treat and serve LGBT patients and families:

- Be mindful of biases. In a study of over 18,000 healthcare providers, researchers found that heterosexual providers had widespread implicit preferences for (e.g., increased comfort with) straight people over lesbian women and, in particular, over gay men. Similarly, lesbian and gay providers held implicit and explicit preferences for lesbian women and gay men over heterosexuals, and bisexual providers held mixed preferences. Researchers called for further investigation as to how implicit sexual prejudice affects care (Sabin, Riskind, & Nosek, 2015).

- Educate providers and support staff about LGBT-inclusive approaches. In addition to increasing knowledge and skills, these experiences are also moderately effective in changing attitudes (Sabin et al., 2015). HEI participants can access training programs at no charge, and the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA) provides free access to a four-part webinar series on LGBT healthcare (see Resource List).

- Provide more targeted training as indicated. For example, registration and admission staff should be trained to ask questions about sexual orientation, gender identity, and preferred name and pronoun while respecting the patient’s right to privacy. The Fenway Institute, which provides education and training on LGBT issues, has developed a toolkit for collecting information about sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings, including suggestions for how to ask specific questions (see Resource List).

- Employ methods likely to mitigate implicit biases, such as use of clinical guidelines, development of policies to promote objective decision-making, inclusion of counter-stereotypical experiences in educational programs, and eliminating provider discretion from decision-making (Magdali, 2015).

- Provide guidance on LGBT-specific health issues. Numerous resources are available for this purpose. GLMA has developed four separate fact sheets, one each for lesbians, gay men, bisexual individuals, and transgender individuals, identifying the top 10 issues that patients in each group should discuss with their healthcare providers (see Resource List). ECRI Institute has developed a tool for providers addressing the special issues faced by LGBT individuals who experience intimate partner violence (Figure 1).

- Avoid social assumptions. Providers may make assumptions about a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity that affect how they engage with that individual, such as assuming that an older man has a wife who is caring for him. These assumptions can make an LGBT patient uncomfortable even if no harm is intended. A patient who has a masculine or feminine appearance or name may have a different birth gender than the gender the patient identifies, and a patient wearing a wedding band may have a same-sex spouse.

- Avoid assumptions that could erroneously influence clinical decisions. For example, a sexually active individual who presents as male but has female reproductive organs could be pregnant and require appropriate precautions for certain procedures and medications. Similarly, office staff must be prepared for transgender male patients who request mammograms and Pap screening tests and for transgender female patients who require prostate exams.

Providers and organizations can take the following steps to create a welcoming environment for LGBT patients and families:

- Display HEI leadership designation and other indicators of inclusion (e.g., the rainbow flag, a pink triangle, and/or a safe zone sign) on placards, staff badges, and the organization’s website alongside its patient nondiscrimination and visitation policies.

- Identify LGBT-welcoming providers at the organization through a website or directory. GLMA also maintains a provider directory for listing LGBT-welcoming physicians and other healthcare professionals at no charge.

- Ensure that the organization’s website and materials in waiting rooms and other surroundings visually reflect LGBT patients and families.

- Provide the option of gender-neutral restrooms, which can also serve parents and caregivers assisting other-sex children and individuals with disabilities.

- Develop rooming policies proactively rather than waiting until a transgender patient is admitted. Lambda Legal provides guidance on transgender-affirming hospital policies, such as room assignments and protocols for interacting with transgender patients (see Resource List).

- Ask about a patient’s preferred name and pronoun. A transgender patient’s legal name in hospital records may be different from the patient’s preferred name if the patient has not changed their legal identity documents, but people who are transgender will have a better experience when they are called by their preferred name and gender. Hospitals might consider the approach used by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital: It included a flag in patients’ electronic medical records to specify how each patient prefers to be addressed, as well as to provide other pertinent information.

- Design inclusive forms. Admission, registration, and other forms should provide inclusive options that allow LGBT patients to voluntarily self-report sexual orientation and gender identity, as The Joint Commission recommends in its field guide. The forms should provide options to identify a relationship status other than husband or wife and to ask about a child’s parents or guardians in a way that is inclusive of same-sex parents.

Looking ahead

Given the dynamic and multifaceted nature of the driving forces behind LGBT inclusion, implementation of best practices for care delivery will continue to be a moving target across the continuum of care for some time. For example, medical schools, which devote a median of five curriculum hours to LGBT-related issues, have been called upon to better address the needs of LGBT patients (Hollenback, Eckstrand, & Dreger, 2014) and students (Snowdon, 2013). Beginning in 2017, achieving HEI leadership designation will require many additional best practices aside from the original four criteria (Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 2016). Long-term care facilities can also expect increased scrutiny of their practices for LGBT equality (LGBT MAP/SAGE, 2010). Providers and organizations may want to familiarize themselves with the following resources to support ongoing efforts toward inclusion.