Stepping Out of the Classroom: Simulate to Educate

May / June 2007

By Zukari Logan, RCIS, and Emily Conner, RN

Patient safety is the optimal goal in healthcare delivery. Patients rely on the fact that their healthcare providers are properly trained on the most recent technology available. Providing current and effective training to healthcare providers can be a challenge in an era when healthcare institutions are dealing with increasing costs and decreasing reimbursement. However, the importance of education and maintenance of skills should not be overlooked. How can we ensure that healthcare professionals have received the most effective training without putting patients at harm? Traditionally, healthcare organizations have used classroom lecture and simple mannequins as the preferred methods of teaching patient care management skills, disease processes, and safe equipment operation. These educational programs, including staff and nursing orientation, can be costly, time-consuming, and not reflect fully the comprehension and skills application of healthcare providers.

Educators must consider that healthcare professionals are adults, and adult-learner populations pose a challenge to effective delivery of content. According to Malcolm Knowles, creator of the theory of adult learning and director of the Adult Education Association of the USA, adult learners are autonomous, self-directed, and have accumulated a foundation of life experiences. They tend to be goal-oriented, practical, and they value relevance. Adult learners also are motivated by cognitive interest and by any form of escape that provides a break in their routine. Stimulation of senses during the process of learning reinforces skills and allows learners to retain information and transfer knowledge learned to the clinical setting (Lieb,1991).

Dr. JoDee M. Anderson (2005), assistant professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, feels that simulation-based training represents an evolution of a teaching paradigm in which the needs of the adult learners are met more effectively. This type of training increases competency and, more importantly, improves patient safety. Simulation training has evolved to become a cornerstone for educating healthcare professionals, and with the advent of the computer generation, simulators have become increasingly lifelike.

Simulation training has become increasingly popular in the past several years and is being used as an effective way to evaluate employee response to various situations. It can be used to measure knowledge, skill, and ability. Simulation provides healthcare professionals the opportunity to practice clinical-based skills in a risk-free environment with the combination of haptics (sense of touch) and patient scenarios with real images. This environment allows for mistakes to be made without detrimental consequences to a real patient.

Two types of simulation are available: high-fidelity and low-fidelity. High-fidelity simulation utilizes very realistic materials and equipment to represent tasks that individuals must perform. Low-fidelity simulation uses materials and equipment that are less similar to what is used on the job. An example of low-fidelity would be presenting a verbal scenario in a hypothetical situation and having a person describe how he or she would respond (Havighhurst, et al., 2005). The use of high-fidelity simulated scenarios allows healthcare professionals to train in a safe but realistic environment, utilizing cognitive and technical skills simultaneously. One facility that uses a high-fidelity simulator is Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.

Piedmont Hospital

Piedmont Hospital is a 458-bed acute tertiary care facility offering all major medical, surgical, and diagnostic services. Located on 26 acres in the North Atlanta community of Buckhead, Piedmont is a private, not-for-profit organization with 3,700 employees and a medical staff of more than 900 physicians. Piedmont received the 2006 Distinguished Hospital Award for Patient SafetyTM from HealthGrades, and was named one of the nation’s Most Wired hospitals in the 2006, 2005, and 2004 “100 Most Wired” survey and benchmarking study. Piedmont Hospital is a member of Piedmont Healthcare (PHC), a not-for-profit organization.

Piedmont Hospital has incorporated a simulation education system into their clinical training programs. The system mimics a cardiac catheterization lab, intensive care room, or emergency department by incorporating various monitors and medical equipment. It uses a simulated patient named Simantha®, who responds to the clinician’s decisions and actions, tactile force-feel technology, and interactive courseware as well as performance metrics to track performance and progress. Unlike typical computer-based training, patient outcomes are not predetermined. Each simulation experience is unique because it is driven by the participant’s decisions and skills in managing the complex medical challenges of the clinical scenario.

Simulation Training Study

The information for this case study was gathered over a 1-year time frame and included two groups of critical care nurse residents. Group One consisted of new nurse graduates with less than 1 year of clinical practice who entered into a 6-month critical care residency. These nurses will fill positions in the neuro, medical/surgical, cardiac care, intermediate intensive care, and cardiovascular intensive care units. Group Two consisted of new nurse graduates and nurses with clinical practice experience but new to Piedmont Hospital. These nurses fill positions in the emergency department, transplant, and intermediate cardiac care.

Traditional Program

Each group of nurses attended a 10-day critical care class and completed 80 hours of lecture time via traditional methods in which the following topics were discussed: cardiovascular system, neuro assessment, pharmacology, gastrointestinal system, urinary system, endocrine system, infection control, patient education resources, arrhythmias, respiratory, invasive and non-invasive cardiac procedures, cardiovascular disease, and genetics. Of those 80 hours, 7 hours were dedicated to hemodynamics and pulmonary artery (PA) catheter insertion. The content included the basic fundamentals of hemodynamic waveforms and an introduction to the catheter. This traditional form of education makes the assumption that there will be an improvement and increase in cognitive skills.

Assessment

Nurses who completed this form of traditional training verbalized a feeling of limited knowledge or no understanding of the theory and functionality of PA catheters and hemodynamic waveforms and its components. This lack of understanding can affect one’s confidence and critical thinking and ultimately compromise patient care and safety.

“I understood the concept of catheter insertion, but when they started getting into the waveforms, I felt completely lost. It was too much information to process in a short period of time.” —Christine O., RN

“There was a lot of information given. I didn’t really understand the different ports and how they worked.” —Rey B., RN

“The class would have been better if we were given a chance to get hands on experience along with the lecture. The instructor mainly handled the catheter while she was talking.” —Natalie H., RN

Intervention

Given the opportunity to evaluate the courseware offered in the simulation program, Piedmont’s nursing coordinator for new nurse graduates determined that it would serve as supplemental training to current traditional methods. Graduate coordinators selected which series of courseware residents would complete. Nurse residents were each given a set amount of time to complete training. The simulation coordinator recorded attendance, test scores, and completed courses, and provided a training report on each resident.

Simulation training was used in two different ways. Training for both groups included lecture, patient care assessment, evaluation of lab values and diagnostic tests, and hands-on simulated patient care management. However, the lecture and simulation time for each group differed. Group One completed 11 hours of simulation training; Group Two completed 4 hours of simulation training. Group One received 4 hours of lecture discussing the different types of hemodynamic waveforms, the components of each waveform, monitoring scales, PA catheter insertion, valvular abnormalities, and pressure abnormalities. They then received 7 hours of simulation training. Group Two received 2 hours of hemodynamic lecture to reinforce concepts received during the hospital classroom lecture followed by 1.5 to 2 hours of simulation training. Content included hemodynamic waveform identification, the components of each waveform, and monitoring scales for the left and right sides of the heart and anatomy. In addition, an interactive video was shown on the insertion of the PA catheter. Each simulated case scenario allowed students to put into practice the concepts learned by completing skills tasks.

Each resident group completed a normal hemodynamic patient scenario on their initial visit. Group One completed other scenarios during the length of their 6-month program. Other patient scenarios included cardiac tamponade, pulmonary hypertension, sepsis, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and RV infarct with a patent foramen ovale.

Once the history and physical assessment had been reviewed, residents were encouraged to start thinking about potential diagnosis and possible hemodynamic measurements. In the simulation room, residents were assigned roles for the procedure: physician role or nurse role. In the physician role, responsibilities included assessment of baseline vital signs, PA catheter insertion, recognition of correct waveforms for each chamber, and correcting any adverse events. In the nurse role, responsibilities included medication administration, monitoring vital signs, recording waveform measurements, performing cardiac outputs, and management of the virtual crash cart.

Evaluation

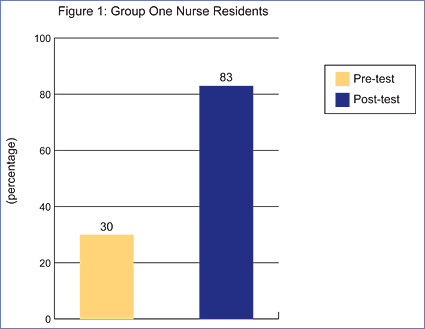

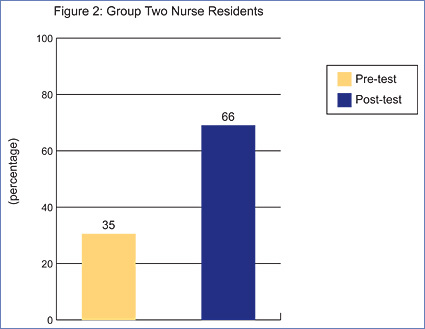

Once the simulation was completed, a post-procedure debriefing was initiated. During this time, discussions focused on the treatment of possible complications and post-care patient management. Pre- and post-tests were administered in order to measure any change in knowledge acquisition (Figures 1 and 2).

![]()

![]()

The above figures reflect participants’ average test score percentages when tested on basic waveforms and waveform identification with PA catheter insertion.

Nursing residents from both groups showed a significant increase in attainment and retention of information concerning hemodynamics and pulmonary artery catheter insertion. Group One showed a 53% increase in their knowledge base while Group Two showed a 31% increase according to the post-test. Residents from both groups expressed their time in the simulation center provided a better understanding of hemodynamics and how certain disease states will affect patients. This understanding allows nurses to identify changes in patient status and initiate proper treatment earlier.

Conclusion

Advancements in technology provide many ways to make improvements in every area of life, including education. In the healthcare arena, the continued focus is on improving quality patient care practices and minimizing in-hospital sentinel events. Hands-on practical application of knowledge is a key step to improvement. The nurse residents at Piedmont Hospital have been given this opportunity, and their community is reaping the benefits.

Zukari Logan serves as a clinical education specialist for Medical Simulation Corporation. She is responsible for providing adjunct educational training for hospital staff as well as the development of department specific education programs. Zukari is a registered invasive cardiovascular specialist with 13 years of invasive cath lab experience and 18 years of clinical experience. She is also an ACLS instructor and offers recertification classes at her host center. Logan may be contacted at zlogan@medsimulation.com.

Emily Conner serves as a clinical education specialist for Medical Simulation Corporation. She is a registered nurse with 13 years of experience in patient care. She has focused her profession on the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Emily has been a member of the Speaker’s Bureau for the Society of Invasive Cardiovascular Professionals and has been active in local chapter involvement. She is also a member of the American Nurses Association. Conner may be contacted at econner@medsimulation.com.

References

Anderson, J. M. (2005). Educational perspectives: Introduction to simulation-based training. NeoViews, 6(9), e411. Available at www.neoreviews.org.

Havighhurst, L. C., Fields, L. E., & Fields, C. L. (2005). High versus low fidelity simulations: Does the type of format affect candidates’ performance or perceptions? Virginia: Fields Consulting Group.

Lieb, S. (1991, Fall). Principles of adult learning. VISION. Available at www.honolulu.hawaii.edu/intranet/committees/FacDevCom/guidebk/teachtip/adults-2.htm