Smart Pump Workarounds: What’s the Legal Risk?

March / April 2012

![]()

What’s the Legal Risk?

Smart Pump Workarounds: What’s the Legal Risk?

|

|

| Photos Courtesy of CareFusion |

In the past few years the need to improve intravenous (IV) medication safety has been heightened by several highly publicized reports of medication errors. At Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis, heparin administration errors led to the deaths of three premature infants. The actor Dennis Quaid’s newborn twins almost died of heparin overdoses. In Wisconsin, a teenage mother in labor died because bupivacaine was administered intravenously instead of epidurally. Fatal overdoses also highlighted the legal risks facing the nurses and other clinicians involved in such errors.

For the nurses and pharmacy technician at Methodist Hospital, the prosecuting attorney determined that the babies died from a system error that resulted in an accidental medication error. But in another case, a pharmacist spent 6 months in jail and lost his license permanently after failing to detect a technician’s compounding error that resulted in the death of a 2-year-old child. In Wisconsin a nurse who failed to use the barcode medication system in the care of a laboring patient and administered a fatal dose of narcotic was initially charged with two felonies and lost her license to care for federally funded patients for 5 years.

|

Andrew D. Harding, MS, RN, CEN, NEA-BC, FAHA, FACHE Michelle Mandrack, RN, MSN Julie Puotinen, PharmD, BCPS Kathy Rapala, DNP, JD, RN Timothy O. Wilkerson, JD |

A 2010 survey showed that 66% of hospitals had implemented smart pump technology (State of Pharmacy Automation, 2010) designed to help prevent IV medication administration errors. But hospitals still struggle to attain high rates of compliance with their use. What are a nurse’s legal risks if smart pumps are available, but she or he chooses not to use the safety technology or overrides an alert and administers a dose that is outside the smart pump’s dosing limits and results in harm to a patient?

On June 17, 2011, a panel of distinguished experts (Contributors, page 20) addressed this question in a nation-wide webcast hosted by the CareFusion Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence. Tim Vanderveen, vice president of the Center, moderated the discussion. This article is drawn from their discussions of nurses’ potential legal risks of not using smart pumps and the approaches hospitals have used to improve compliance and aggressively manage alerts.

Tim Vanderveen: Drew and Tim, in a recent article you state:

When this technology is available and not utilized, litigation could be successful in finding fault on the nurse. Therefore, nurses should use the available smart pump technology every time when administering intravenous therapy (Harding et al, 2011).

What prompted you to write this article?

Andrew Harding: About 3 years ago I was working for a hospital that had recently purchased IV smart pumps in response to an adverse patient event. A few months after go-live, still only about 30% of IV infusions were being delivered using the smart pump software. We determined that there were valid barriers to nurses’ using the pumps, but nagging legal questions remained. If a smart pump is provided but a nurse doesn’t use the safety software, what are the legal ramifications if a patient is injured from a medication error that smart pump use could have prevented?

Tim Wilkerson: As a member of an Institutional Review Board in Massachusetts, I wanted to examine the intersection of new, advanced medical technologies and the potential liability that nurses face by failing to use them. Smart pumps hold great potential to reduce human error, but in cases where nurses fail to use them, serious potential liability exists for the nurse, other assisting medical providers, and the hospital.

Tim Vanderveen: Michelle, in your work with ISMP, how often do you see compliance issues with patient safety technology such as smart pumps, even after a serious event has occurred in a hospital? How much of a factor is failing to recognize the risks or see the value of the technology solutions?

Michelle Mandrack: Hospitals are still evolving in their ability to maximize the safety potential of this technology. There are many reasons why clinicians may bypass the dose-checking software: clinical emergencies, time pressures, the extra work it takes to use the technology, alerts that may not be credible, a library that does not reflect recent changes in practice, etc. Staff often has a limited appreciation of the inherent risks in IV medication administration.

Medication errors predominantly occur during the prescribing (39%) and administration (38%) phases of medication use. Prescribing errors are more easily detected before they reach the patient, but only about 2% of errors that originate during drug administration are intercepted before reaching the patient (Leape et al., 1999). More than 50% of harm results from medication errors that originate during drug administration.

IV medications errors are particularly dangerous because IV medications have immediate bioavailability and often a narrow therapeutic range. These errors are associated with about 54% of potential ADEs and increased risk for harm. (Kaushal, 2001; Fields, 2005; Cohen, 2007) Once infused, reversing the systemic effects of IV medication administration can be extremely difficult. To improve IV administration safety, it’s important to use an interdisciplinary approach, build an effective drug library, and assist staff to see the value of the technology and the benefits that they gain by consistently incorporating it in their workflow.

Tim Vanderveen: What is the role of personal accountability in helping to prevent errors?

Andrew Harding: Personal accountability is really professional accountability. Individuals are licensed by their state as nurses, pharmacists, or physicians to ensure the public that they have a baseline professional competency. A lot of research describes why these professionals make mistakes: fatigue, stress, cognitive bias, workload, interruptions in our work, environmental design, workflow, lack of standardization, the workplace culture, and then communication barriers or failures. Addressing these issues requires proper management oversight, shared governance, a just culture, work/life balance, lifelong learning, and a culture of safety to help provide the systems and the work environment that promotes safe, patient- and family-centered care.

Photos Courtesy of CareFusion

Tim Vanderveen: Many hospitals still struggle with getting nurses to comply with using smart pumps even 10 years after their introduction. What does the law say about failing to use available technology?

Tim Wilkerson: In order to prove negligence, a plaintiff must show 1) that there was a duty, a legally recognized relationship between the parties; 2) that there is a standard of care at issue, a required level of action or conduct; 3) that a breach of that duty occurred by failing to meet the requisite standard of care; 4) that the defendant’s actions or conduct was the cause in fact and proximate cause of the plaintiff’s harm; and 5) that there were actual damages or injuries resulting from the defendant’s (nurse’s) breach of their duty to act according to the recognized standard of care.

A plaintiff (patient) must also show that use of a specific technology has become sufficiently widespread or readily available so that not using the technology would deviate from the generally accepted standard of reasonable care for nurses.

The rule of “reasonableness” was established in the 1932 T.J. Hooper case in which two tugboats and barges were sunk during a storm. The barge operators sued for negligence, and the judge ruled that the tugboat operators breached their standard of care by failing to have radios on their boats and, therefore, not anticipating the storm’s potential danger and severity. The judge reasoned that where the use of a technology provides an essential precaution to safety and welfare, there’s no defense for its omission or failure to use.

Tim Vanderveen: If a hospital invests in smart pumps or other safety technology, and a nurse chooses not to use that technology and makes a serious error, does the hospital have any liability for that error?

Tim Wilkerson: Yes. The target for potential civil liability is much larger than the nurse who may have actually breached the duty of care. All personnel involved in the care of a patient are expected to provide reasonable and skilled medical care. When a breach in that duty occurs by the actions of a nurse, the potential liability will run up the chain of the command all the way to the medical institution itself. This is based on “agency liability.” The employee (nurse) as agent fulfills his or her job responsibilities through either express or implied authority provided by the employer. That authority exposes the hospital to liability when a nurse’s actions, which are conducted on behalf of the hospital, constitute a breach of standard care resulting in injury to a patient.

A hospital could also potentially be liable under an alternative legal theory of respondeat superior. This is a broad legal principle that an employer is liable to a third person for any injury which results approximately from the conduct of an employee acting within the scope of his or her employment. If it is deemed that the nurse breached the standard of care in not using available smart pumps within the scope of their employment, the hospital employing the nurse would likely be vulnerable to a lawsuit.

Tim Vanderveen: Kathy, as a nurse, lawyer, college professor, and risk manager, what would you add to this discussion?

Kathy Rapala: I think it’s important to realize that legal and patient safety are two separate frameworks. The legal system focuses on ultimate responsibility and who’s to blame. There is an adversarial, plaintiff v. defense mindset, and discovery methods that tend to discourage open information sharing. Patient safety focuses on systems, human factors, and why things happen. For example, as human beings, we’re only able to hold on and process five to seven chunks of information; anything more than that is lost. Any practitioner in our busy practices might have a piece of information slip out just because they have so much on their mind. So, the focus in patient safety is on sharing and fixing.

A high rate of noncompliance indicates that something’s wrong with the process, for example, education, or implementation. Jumping to “Why didn’t the nurse use the technology?” doesn’t get to the root cause of the error. Maybe the nursing staff is getting too many “nuisance” alerts. Maybe the data set isn’t well managed, so it doesn’t fit the nurses’ practices. Maybe a nurse has a new admission coming in and a patient coding, and has to choose between programming the pump in detail and responding to the code. There can be lots of reasons.

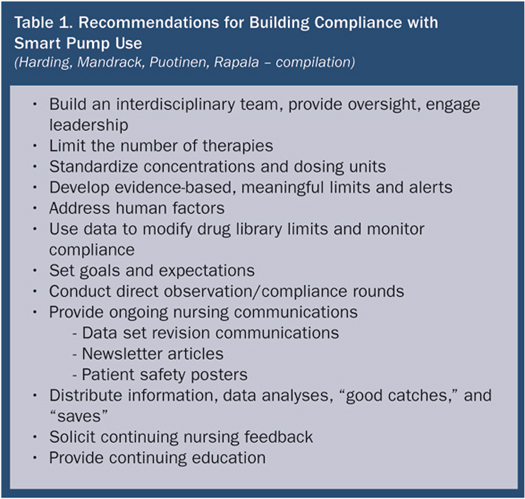

It’s important to remember that the implementation often sets the tone. If an organization lays the proper foundation of good education and good drug-library data sets, the implementation will be a lot easier. Work out all the inconsistencies in the system (Table 1) before looking at onerous consequences for nurses and staff.

It’s also important to remember that not only nurses use and program the pumps; other practitioners such as physicians use the pumps, as well.

Tim Vanderveen: Is failing to use an available smart pump a breach of the accepted standard of care?

Tim Wilkerson: As smart pump technology becomes more prevalent throughout the country, courts will be more inclined to find that smart pumps are the accepted standard of care. Because that “accepted standard of care” is ultimately difficult to define, a much easier and simpler rule for nurses should be: always use the more advanced technology when it’s available.

Tim Vanderveen: Could failure to use an available technology result in civil and/or criminal proceedings against a caregiver and personal liability lawsuits?

Tim Wilkerson: Yes. If severe negligence resulted in serious permanent injury or death, the nurse could be found both civilly and criminally liable for failure to use available technology.

Tim Vanderveen: If a nurse chooses to bypass a safety system, is the nurse covered by malpractice insurance?

Tim Wilkerson: Malpractice insurance should never be viewed as a safety net for failing to uphold your duty and responsibility as a medical provider. Jeopardizing patient safety because you have malpractice insurance is the very definition of negligence. Also, once a policy’s limit is reached, any remaining legal bills and plaintiff’s damages come out of the negligent nurse’s pocket.

Tim Vanderveen: Creating smart pump libraries is a complex process, and setting soft and hard limits has proven challenging for virtually every hospital that has implemented the technology. How do you think the way the drug library is created contributes to compliance issues?

Julie Puotinen: First, the limits and alerts need to be meaningful. On a non-telemetry unit, it makes sense that a potassium infusion greater than 20 mEq per hour fires an alert. But for our intensive care unit (ICU) nurse infusing potassium through a central line, that might be perceived as a nuisance alert. If alerts are perceived as clinically unwarranted, you’re going to drive practice toward overrides or noncompliance.

Garnering robust feedback from nursing during the library development process is essential. During these sessions the staff can be oriented to how the library was developed based on literature, guidelines, internal events, and your institution’s practice protocols. It also provides valuable insight into how drugs are actually used in clinical practice. Finally, it’s imperative that leadership sets the expectation that using the safety technology is essential (Table 1, page 23). It’s also important to develop a response mechanism so that nurses can provide feedback on a drug library. Nurses who don’t feel like they have a voice to enact change will develop a work-around, which may be noncompliance.

Tim Vanderveen: Julie, what have you accomplished by aggressively managing the pump libraries and using wireless connectivity to implement frequent changes?

Julie Puotinen: Our 15-hospital system deployed smart pumps over a period of 18 months. We’ve maintained a single library across all those hospitals, and had multiple library review sessions at each hospital before pump deployment. We had already standardized adult IV drip concentrations and IV administration guidelines system-wide before pump implementation, which helped a great deal.

To minimize nuisance alerts, we analyzed drugs associated with the most alerts and overrides, drug profiles with the lowest compliance, and issues identified by practitioner feedback. We also conducted medication-use evaluations that were presented to our System Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. We changed some of our protocols and provided education to both nursing and medical staff. Overall, we have reduced our alerts by 63% since go-live, while adding value to the integrity of our library.

Tim Vanderveen: You started out with pretty high compliance in many of your hospitals. How have you addressed the challenges in maintaining that high compliance?

Julie Puotinen: With 400,000 infusions a month across 15 hospitals, one of the challenges was defining a process to maintain all the data while staying connected with the end-users. We have two mechanisms for accomplishing that. Site Analytics Teams at each of our hospitals are responsible for managing each hospital’s data, and a System Analytics Team looks at the aggregated data for the system as a whole. Nurses from the site teams also sit on the System Analytics Team and help bridge the two. Both the system and site teams are responsible for helping ensure that compliance does not decrease and for bringing suggestions on how to further improve our performance.

For example, in February 2011 our system compliance rate for pediatrics was 75%, lower than we wanted. So we analyzed data, engaged the System Pediatric Nursing Committee, and added value to the pediatrics drug library by enhancing some of the Guardrails in IV fluids and really focusing on soft and hard limits. We also re-educated staff on what the different age limits were for our neonatal, pediatric, and conventional profiles and when they should use each profile. By April 2011, system compliance for pediatric was 90%.

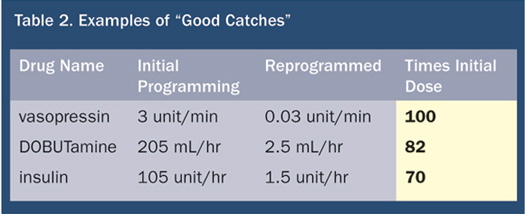

We’ve provided information to medical staff committees and our System P&T Committee, so people know what we’re doing with the pumps and that this is another technology that’s keeping our patients safe. We show staff the data, including “good catches” (Table 2). I think when you show these to nurses, they realize, “That could have been me. I really want to use that technology so that I’ve got a pump backing me up.”

Andrew Harding: The goal is to prevent catastrophic patient injury. It remains the goal of every healthcare provider to prevent any kind of harm to patients through the use of these systems and professional critical thinking.

It’s also important to understand some of the limitations of the IV pump. A nurse still has to choose to use the library, select the correct IV therapy, and set the correct rate of administration. Any one of those can be entered incorrectly and never be recognized by the IV smart pump if the entries are within the library guidelines. It won’t be until we have full interoperability between the electronic medical record (EMR), IV smart pumps, patient monitoring equipment, documentation, and direct care provider communications tools that such errors will be dramatically reduced.

Tim Vanderveen: Assuming that the medications being administered are in the smart pump libraries, is 90% or 95% compliance with the use of the safety system sufficient?

Tim Wilkerson: Applying the ruling from Hooper, which is the bedrock legal principle for negligence and technology, a nurse who fails to use smart pump technology, when 90% to 95% of nurses are using them, may be found negligent. The hospital, administrator or procurer of technology who permits the continued use of any other type of IV infusion pump is highly negligent, as well. When you reach those levels of 90% to 95% use, there’s almost no reason why you would administer potentially harmful IV medication through any other type of pump besides a smart pump.

Michelle Mandrack: As long as we have humans in the equation, we’re never going to have practices and systems that are 100% error-free. But we need to maximize their safety potential and certainly avoid harm. And we are making progress. We have to remember that the science of safety is still relatively young, and organizations are in different places along the learning curve.

Leadership is obviously crucial in driving and sustaining these gains in medication safety. This includes corporate accountability for system design. Managers are accountable for facilitating safe behavioral choices with staff and for coaching anyone who displays at-risk behavior. Frontline staff, middle managers, and executives are all accountable for safe behavioral choices. The adoption of a culture of safety is key; it’s the foundation for all of the work.

It’s not enough to purchase the smart pumps, get them out and hope that the error-reduction software is going to be used. We have to help healthcare practitioners recognize that the use of the smart pump drug library is not an option that should be casually bypassed. We need to really maximize the use of the data that comes from the technology. It takes a lot of work, but when we use the data well, it helps identify opportunities to enhance the value of the safety software to the front-end user, provide more clinically relevant alerts, and promote much more consistent use.

There’s little doubt that smart pumps can save lives if the drug libraries are properly designed and used. We’ve got to make sure we’re using them. In fact, in the not-too-distant future, failure to use this technology is likely going to be considered suboptimal care.

Tim Vanderveen is vice president of the CareFusion Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence in San Diego, California. He may be contacted at tim.vanderveen@carefusion.com.

The following questions were asked of the panel by members of the webcast audience on June 17, 2011.

Audience Q&A

Question: What is the nurse’s and the hospital’s liability if a smart pump feature is available—for example, a feature that allows a nurse to bolus a drug from a bag as opposed to a vial or syringe—but the hospital chose not to implement it, and then the nurse made an error that that feature could have prevented?

Kathy Rapala: I think if an error occurred, the hospital could be liable to some extent, depending on damages and other considerations. It’s important to remember that within a healthcare system, there are pros and cons to every choice. We hope to make the best choice, but sometimes we don’t. Even with a really thoughtful decision-making process in place, an event may occur. It’s in the hospital’s best interest to make sure that they’ve gone through a documented, thoughtful decision-making process, looked at the state laws and regulations and the evidence behind that. Sometimes there’s no clear evidence on either side, so checking with colleagues and documenting the entire process is important.

Question: What if the hospital sets a limit that generally is the right one, but for a particular patient, a dose within the established limits causes harm?

Tim Wilkerson: In an instance where a person is injured because of an abnormal reaction to a medication, then the hospital is less likely to be found negligent. There must have been other factors present that led to the harm, and that mitigates the nurse’s and hospital’s liability. Anytime a hospital establishes a policy or procedure hospital-wide that a court would say deviates from the national or local standard or from accepted or diligent practices, I think they would be liable. Anytime a hospital establishes a hospital-wide policy or procedure that conforms to a recognized national or local standard, I think they are less likely to be found liable.

Question: Some physicians insist on prescribing dosing units that are not in the drug library. For example, one cardiologist prescribes nitroglycerin in mL as opposed to mcg. As a result, a nurse will program nitroglycerin at 400 mcg, which is outside our drug library and triggers an alert. The hospital allows this to occur. What liability is there for the nurse, if there’s a negative outcome?

Kathy Rapala: Depending on the healthcare system, it can be a valid order, and the physician can certainly order it. But it would be easier for the staff if dosing units were standardized, and the hospital should look to best practice for order-writing guidance. If you’re using electronic order entry, sometimes order sets can help to shift the practice, but I think it happens over time. Again, a thoughtful, evidence-based approach will lessen liability concerns for the practitioner.

Question: We have not been able to find a smart pump that is compatible with MRI. As a result, we’re using an older syringe pump, for drugs like fentanyl, propanol, or heparin that can’t be stopped during the MRI. Are smart pumps available that are compatible with the MRI setting?

Tim Vanderveen: Virtually all of the devices on the market today contain ferrous metal and are not MRI compatible. What many hospitals have done is to use extra-long tubing and have the pump out of the magnetic field.

Question: Any suggestions on how to get anesthesiologists to use the smart pumps in the operating room?

Andrew Harding: I’ve found anesthesiologists to be the toughest group to convert to smart pump use. It’s a matter of showing them those examples of “good catches” and “saves” that the pumps have provided in either the operative or post-op setting. Also working with the leadership of that group to make patient safety a priority and getting them involved in changing the anesthesiologists’ behaviors to use these devices.

Julie Puotinen: If you can, sit in the PACU or the anesthesia lounge with a smart pump. We’ve found that anesthesiologists don’t always show up for the initial training or know how to use the pump, even if they think they do. Give a brief tutorial after implementation, so they actually know how to give the drugs. Also, they may give you feedback on what their issues are, and it might be something in the drug library that you can address.

Tim Vanderveen: I would encourage you to google the Anesthesia Patient’s Safety Foundation’s Spring 2010 newsletter, which has an article on Wake Forest Baptist Hospital in North Carolina, where the smart pump implementation really led by the anesthesia department. (Vanderveen, 2010) That might be something you could share with your anesthesia department.