Simulation – Patient Safety Simulations: Driver of Cross-functional Collaboration

January / February 2005

Simulation

Patient Safety Simulations: Driver of Cross-functional Collaboration

![]()

Blame and punishment, missed hand-offs, complex regulations, and empowerment struggles are key issues that hamper the healthcare system’s ability to provide high-quality patient-centered care. In our dynamic and complex healthcare environment, recognizing that we have the ability to implement enduring systemic change from our individual spheres of influence is a constant challenge. Multi-stakeholder patient safety simulations — “patient safety wargames” — are experiential exercises that present participants with scenarios that must be addressed by participant teams in a real-time environment. These simulations can play a valuable role in helping health providers move beyond their traditional roles and comfort levels to stress test alternative strategies for improving patient safety in a dynamic, yet risk-free, environment.

It is well understood that preventable medical errors have disastrous implications. HealthGrades, Inc., estimates that medical errors are responsible for as many as 195,000 deaths of hospitalized patients a year. As a nation, we have invested significant resources and time in furthering our understanding of the complex and systemic nature of the safety epidemic in our health systems, but we need urgently to increase our focus on addressing issues that could improve the safety and quality of care in our medical institutions today.

Lack of communication among stakeholders in the continuum of care is a complex issue, and identifying leverage and intervention points is often a daunting task. A simulated patient safety crisis, presented at the institutional level, is an effective means to support the identification of unique cross-disciplinary issues and collaborative solutions that can have an immediate impact on the culture of safety.

Two Scenarios

In the spirit of taking concrete action to address patient safety, over 50 healthcare professionals participated in a patient safety simulation developed by Booz Allen Hamilton and Consumers Advancing Patient Safety (CAPS) for a national conference sponsored by the American Board of Quality Assurance and Utilization Review Physicians (ABQAURP) in Tampa, Florida, in October 2004. Attendees worked through two complex scenarios in multidisciplinary teams of key health stakeholders (doctors, nurses, administrators, and support personnel). The teams were challenged to develop actionable approaches to safety issues in a hospital and received real-time feedback from multiple perspectives, including patients and the media. Personalizing the patient safety experience in this manner helps drive change at the front lines of patient care.

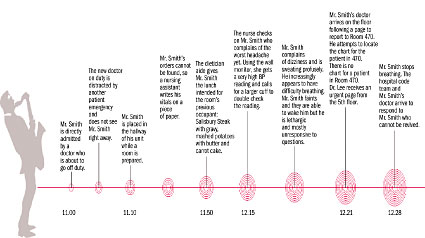

As a group, the participants were introduced to the first scenario, in which a morbidly obese, diabetic, 54-year-old African-American male, Mr. Smith, visits his primary care physician with what have become regular complaints of headaches due to lack of compliance with diet and medication regimens. The participants learned about the cast of characters, the key events, and the basic facts. (The graphic of Scenario 1 describes the sequence of events.) The group divided into assigned teams, one team each representing hospital administration, physicians, nursing, and support services (e.g., dietary, laboratory, pharmacy, etc.). Working with a trained facilitator (and healthcare expert), the teams were tasked to identify the immediate and root causes of the patient crisis and to identify immediate priorities and actions. Based on their assigned discipline, participants discussed what they needed to communicate, to whom, and when. Communication methods and content questions were key as the game designers applied external shocks via media inquiries and the revelation that Mr. Smith was a famous local musician, mandating immediate answers and responses.

![]()

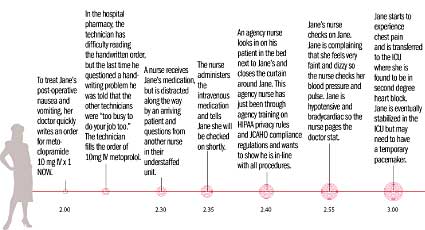

Participants reviewed the available information and discussed what else they needed to know, which groups might have additional information, and what actions were appropriate. Game designers added new developments and challenges by interrupting each groups’ deliberations with experts who role-played as members of the patient’s family and the media. As teams concluded their responses to the first scenario, each team identified barriers across the continuum of care that might prevent them from implementing their ideas for improving patient safety. In the second scenario of the day (see graphic), the teams built upon their experiences in the first event and introduced their own innovative approach to interdisciplinary collaboration. Thinking outside the box (and outside the expectations of the game designers), the administration team established a multidisciplinary response team to investigate the patient safety incident and develop a more coordinated response to the event.

![]()

Throughout the simulation, each stakeholder experienced institutional patient safety from several different perspectives. Either through role-playing or through feedback from patients and the media, physicians gained a better understanding of the role of the patient, nurses, physician, administrators, and media. At the conclusion of the simulation, each participant came to appreciate the cross-functional issues that lead to catastrophic flaws in patient safety and that create barriers to effectively providing integrated delivery of care. Moreover, root causes associated with training and communication represent a key leverage point for immediate improvements for the safety of patients and the quality of our healthcare.

Through the simulation, participants were able to identify many key issues and actions that can be addressed at any institution to effectively improve the quality of healthcare, including:

| Multidisciplinary approaches throughout the care continuum. | ||

| • | Stakeholders must work together to address system vulnerabilities. | |

| – | Multi-functional collaboration reduces gaps in the continuum of care. | |

| • | Valuing the role of the patient in the provision of quality care is essential. | |

| – | Quality healthcare includes patient involvement in patient safety. | |

| • | Multidisciplinary teams can reach conclusions more rapidly than homogenous groups. |

|

| – | Break down cultural communication barriers. | |

| – | Multi-functional perspective more rapidly exposes systemic blind spots. |

|

Process improvements are a greater imperative than technology solutions. |

||

| • | Policy work-arounds point to inherent deficiencies. | |

| – | All stakeholders must collaborate on sound policies and procedures to enable quality care, efficient workflow and patient-centricity. |

|

| • | Training is a systems issue. | |

| – | Errors resulting from training inadequacies may represent systems failure rather than individual incompetence. |

|

| • | Low-tech or low-cost solutions — overlooked in the push for system- wide solutions — can improve health quality immediately. |

|

| – | Policy and procedure issues can significantly impact systemic patient safety improvement. |

|

| • | Technology may be an enabler for process streamlining. | |

| – | Technology itself cannot fix flawed processes and may exacerbate them. |

|

Efficiency must not preclude critical safety checks and balances. |

||

| • | Redundancy allows for errors to be caught before reaching or affecting the patient. |

|

| – | Mandatory processes must be in place to ensure stewardship of patient care. |

|

| • | Maintaining the continuity of care across hand-offs is imperative. | |

| – | Safe hand-offs require both stakeholders’ direct and complete involvement in the transition of care. |

|

| • | Safety is at risk when the institutional climate demands shortcuts. | |

| – | Shortcuts are often the result of serious understaffing and a chaotic work environment. |

|

| – | Patients with elective/routine procedures or apparently simple diagnoses are at increased risk within such a climate. |

|

| • | Risk-based approaches should be used when eliminating redundancy. | |

| – | Risk and returns on efficiency efforts should be weighed in consideration of the costs of medical errors. |

|

Institutional transparency and patients’ right to privacy requires a dynamic equilibrium. |

||

| • | Need for an institutional policy on HIPAA and the media. | |

| – | Can’t “plead HIPAA” to avoid the media. | |

| – | Media will find “the story” to tell. | |

| – | Staff should be educated on media response management and guidelines necessary in the HIPAA environments. |

|

| • | Control the message. | |

| – | Proactively and responsibly addressing the media stakeholders protects the hospital and the patient. |

|

| • | Patient advocacy and disclosure should be integral to the quality assurance process. |

|

| • | Patients and families have a right to disclosure in a timely manner about what is known to be true. |

|

| • | Quality assurance process must address perception about what “might” have happened to identify true root causes. |

|

As our nation strives to expand our understanding of the systemic nature of safety and quality issues in healthcare, institutions and providers need to identify critical interventions that can immediately improve our culture of safety, rather than awaiting wholesale system redesign. Patient safety wargames can act as catalysts for change and play a vital role in supporting the development of institutional action plans to proactively address safety issues across diverse multi-stakeholder organizations.

Mark Frost is a principal at Booz Allen Hamilton where he leads the development and execution of business games for commercial, government, and military clients. The games include the AIDS Epidemic Strategic Simulation, the Bioterrorism Wargame, and a series of Patient Safety Wargames to bring key stakeholders together. Before joining Booz Allen, Frost served in the U.S. Navy in antisubmarine warfare (ASW) patrol aircraft and the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson, and taught in the mathematics department at the U.S. Naval Academy. Frost holds a bachelor of science degree in business administration from the U.S. Naval Academy and a master’s degree in operations research from the Naval Postgraduate School.

Nicole Weepie is a strategic simulation associate at Booz Allen Hamilton. In addition to working actively on wargames and strategic simulations for various government, military, and commercial clients, Weepie was the game designer and control team facilitator for patient safety simulations held at in 2004 for HIMSS and ABQAURP. She has a bachelor’s degree in international studies and French from Loras College and a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to recognize the hard work and input of Shannon Songco, Tracy Weatherby, and Christine Fantaskey in the development of this article.