Quality, Cost, and Connected Health

May / June 2008

![]()

Quality, Cost, and Connected Health

![]()

The U.S. healthcare system is arguably designed to care for sick people. Some have effectively argued that is should be relabeled a “sick care” system. This phenomenon has its roots in history, when the link between lifestyle and illness was less clear. It was also a time when individuals often succumbed to acute illnesses such as infectious diseases before they could grow old enough to be affected by the chronic illnesses that are the dominant players in our healthcare landscape today.

When Medicare and Medicaid rolled in, in the 1960s, they created an economic engine to grow and sustain a system that continues to this day to reward episodic care and de-emphasize preventative care. The other historical trend that has led to out-of-control medical inflation is the need employers felt to offer healthcare insurance coverage as an employee benefit. These macro economic effects have provided an opportunity for well meaning professionals involved in the healthcare supply chain to hone their business models and work flows to maximize returns in a fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement system.

So, of course, the correlate is that any innovative approach to care will challenge entrenched workflow and reimbursement methods. Likewise, any attempt at reimbursement reform will be met with extreme caution by providers who have built up systems to maximize revenue in a FFS system. Payers and providers alike know that fee-for-service reimbursement is an innovation killer and that payment reform must pave the way for new models of care delivery. But they participate in a game of chicken, each waiting for the other to make the first move.

In the meantime, the supply-and-demand curve around healthcare services is reaching a breaking point. The demand keeps growing, and the supply remains constant. In this context, primary care physicians are taxed and in high demand. Their natural response to their situation is to demand higher pay for their contribution to the healthcare ecosystem.

Is There Any Way Out of this Conundrum?

There is. It will take persistence and leadership, but the earliest smoke signals are on the horizon suggesting change is at hand.

The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) are undertaking several large-scale payment reform experiments. They’ve all but guaranteed that they will pay differently for the care of chronic illness in the next few years. Which payment mechanism will stick? Will it be pay for performance (P4P) which has its roots in FFS, but where each fee has a withhold that is granted at the end of the year as a performance bonus IF the provider has met certain agreed upon performance metrics? This is perhaps the most mainstream type of payment reform on the market right now, but it is problematic because it still hinges on the payment for services rendered in the office or hospital setting.

CMS is trying some other bold experiments as well. In one, Medicare Health Support, they contracted directly with disease management firms to provide services to the chronically ill. Recent reports suggest that this method has not worked well, and Medicare will likely cease the program. However, a similar project where the direct contracting is done with physician groups (Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries) is going better.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts (BCBSMA) and other Massachusetts payers have been leaders in bringing payment reform (P4P) to the local market. They want to go further. BCBSMA has just declared that they will offer healthcare providers two types of contract opportunities. One is traditional FFS, but the other, more interesting one is a yearly fee for each patient with bonus payments for achieving quality metrics. As you might predict, not too many providers are lining up, but it’s a start.

Unlocking Value by Connecting Patients and Providers

What is going on from the provider’s perspective? We are spending lots of time and energy on implementing electronic medical records. This is laudable because, at a minimum, it will result in improved quality and patient safety. However, it’s not enough.

Early returns from several sources indicate that transferring care documentation to an electronic record does not lead to efficiency gains as hoped. This is an example of one inevitable rule of technology use. If one applies a new technology to an old workflow, the result is either incremental improvement or no improvement at all. The electronic record is an important bit of infrastructure; an important step in the right direction. However, to achieve breakthrough innovation, a new model of care is required.

A number of organizations around the world have been demonstrating on a small scale that technology can be used to provide care outside of traditional care settings and, in the process, achieve improved quality, improved access and improved efficiency.

How is this possible? The core technologies applied are messaging and monitoring technologies. Using these technologies to enhance connectivity between patients and providers has taught us many lessons and led to a number of reproducible outcomes.

1. The biofeedback that sensors provide is a powerful tool for engaging patients in their care plan. Our brains are fabulous at playing tricks on us. Who among us, when asked to estimate our weight for a physician or nurse, has estimated it on the high side? If asked about your exercise frequency and amount, you’d probably also estimate that on the high side. If asked about your alcohol consumption, probably the low side. You get the idea. We are very poor self-reporters of such data.

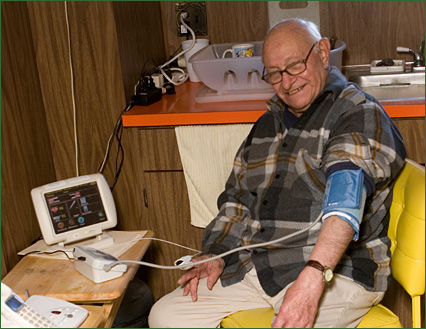

At the Center for Connected Health, we are using sensor technologies right now as tools to encourage health and wellness with certain patient groups. We use weight to track fluid gain in our congestive heart failure patients, glucometer readings to track diabetic control, blood pressure readings to correlate lifestyle changes with changes in blood pressure, and smart pedometers to give folks feedback on their caloric output. In each case the sensor (BP cuff, glucometer, pedometer, etc.) offers a signal that is captured by a device we refer to as a gateway. The job of that gateway is to get the signal out of the patient’s environment (home or workplace) and into a database we call the remote monitoring data repository (this is usually done by analog phone line). Just collecting the data and presenting it back to the patient in an educational context on their own website is a powerful tool to encourage adherence to care plan and self care.

2. Providing this data to healthcare professionals ups the stakes significantly. Now imagine that you are conversing with your doctor or a nurse in her practice. Instead of asking you about your weight for the past few weeks, or your exercise level, the health professional looks at a screen and begins a dialogue with you about how adherent you have or haven’t been to the care plan you agreed on. Scary thought? Nowhere to hide? Perhaps, but once you have embraced the need for certain health behavior changes, these tools promote an honest dialogue with your provider.

Our patients tell us how motivating it is for them to know that someone in their doctor’s office is reviewing this data about them. In some recent focus groups we ran, diabetic patients were quite willing to annotate their personal website with information about diet and exercise to put their glucose readings in context if they were assured that their healthcare provider would look at the data and use it as part of their decision-making. Our heart failure patients consistently tell us how knowing that a nurse will be calling if their weight goes up 2 to 3 lbs is a strong motivator for them to watch their salt intake and stick to their fluid restriction. They tell us how the technology empowers them to be better self caretakers.

3. Electronic communication meets the need in certain care situations. Arguably, exchanging emails or text messages does not allow for the same emotional depth as a phone call or a face-to-face meeting.

When doctors and nurses initially consider the notion of rendering care on line, they often reject it because they feel their patients will be robbed of the emotional bond that an in-office encounter provides. After all, we all know how powerful the placebo effect is: if we believe a therapy is going to help us, it is much more likely to do so. In a positive provider/patient relationship this effect is in play all of the time. The assumption is that all of the verbal and nonverbal cues that are involved in a face-to-face encounter are necessary to maximize this positive therapeutic effect.

![]()

Our experience is different. We recently studied the feasibility of using electronic follow up visits for some of our patients with straight forward, simple conditions. The patient uploads some important information about their illness (for instance, an acne patient might answer some relevant questions and upload a picture of his face) and the doctor answers within a prearranged amount of time. We compared patients who had four such “evisits” in a row to control patients who came into the office for their care. The bottom line was that patients spent significantly less time on evisits, and put their effort in at a time of day that was convenient for them. They felt cared for and by objective criteria, the quality of care was comparable between the two groups. Doctors liked the system just fine. When this kind of system is institutionalized, it’ll be more efficient as well.

Another example of the power of electronic communication is in the area of medication adherence. We know that people don’t take their prescribed medications properly at least 50% of the time. The factors are many and complex, but about 20% of the time, its simple — they forget.

We recently tested the use of a simple phone text message as a tool to remind people to apply their sunscreen. Those who got the text message reminder had double the use of sunscreen compared to those who did not. Imagine the power of getting all prescription users to improve their adherence to their medication plan by 50%.

These examples demonstrate that we are making great strides towards weaving connected health strategies into the fabric of quality patient care. Providers are realizing the power of staying connected to their patients once they leave the medical setting, being able to monitor their vital signs in real time. Patients are more motivated than ever before to get involved in their care, and are empowered by the personalized information they can receive and comforted to know that their healthcare providers are watching. Even employers are jumping on the connected health bandwagon, seeing how employee wellness and disease management efforts can create a healthier, happier workforce while reducing healthcare costs.

Yet, although these tools are all exciting and the results speak for themselves, they are not in widespread use. There are a number or reasons for this. Yes, the technologies are not 100% mature, and the amount of system integration required to make them work is high at this point.

The bigger barrier by far is physician workflow. Remember, workflow is optimized for a fee-for-service environment. When we show our tool set to doctors, they have a predictable reaction. “This is great for patient care, but I don’t have any time for it. I’m too overbooked with my office practice and all of the administrative burden around that.” We consistently hear fear of data overload from our beleaguered colleagues.

However, if you allow your mind to wander a bit, you could see how this type of technology set could streamline that office practice and make the office available to those patients who really need it, while allowing others to care for themselves in the convenience of their home or work place.

At scale, the vision for the doctor’s role goes something like this: spend the morning seeing a few really complex patients and the afternoon checking various quality dashboards that show performance on patients with chronic illness. Send a number of electronic messages (evisits) to patients who need attention. Deal with some exceptions (Glucose is too high. Is a medication change needed? Weight is too high in a CHF patient. Is a boost in the diuretic dose required?). I think you’d agree this lifestyle seems more relaxed for the doctor and would allow larger panels of patients to be cared for.

So how do we get there? That leads us back to payment reform and how it is moving the thinking of physicians in the right direction. Pay for performance is a start. In our own delivery system, this minor adjustment has opened all kinds of creative and healthy dialogue. Doctors are willing to experiment with diabetic monitoring because they are held accountable for the percentage of their patients with HbA1c below 7. Soon we’ll be held accountable to keep blood pressure readings, in aggregate, below 140/90. Blood pressure monitoring will be a powerful tool to help get those with persistent pressures greater than 140 on the right treatment plan quicker.

We are in dialogue with our payers about a number of other interesting payment reform scenarios. Each one gets us a bit farther away from pay for quantity of service (fee for service) and closer to pay for quality of service. If we are paid consistently for quality, this will move our thinking to a population-based approach. In that mindset, the connected health tools describe above will make immanent sense.

The future is bright.

Joseph C. Kvedar is founder and director of the Center for Connected Health, a division of Partners Healthcare that is applying communications technology and online resources to improve access and delivery of quality patient care. Dr. Kvedar is internationally recognized for his leadership in the field of connected health. He is a past president and board member of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA) and co-editor of Home Telehealth: Connecting Care within the Community, the first book to report on the applications of technology to deliver quality healthcare in the home. Dr. Kvedar is also a board-certified dermatologist and vice-chair of dermatology at Harvard Medical School. He may be contacted at jkvedar@partners.org.

References

Clemson, B. (1984). Cybernetics: A new management tool. Cambridge, MA: Abacus Press.