Preventing Wrong-Site Surgery in Minnesota: A 5-Year Journey

November / December 2012

![]()

Preventing Wrong-Site Surgery in Minnesota: A 5-Year Journey

While rare, surgeries and invasive procedures on the wrong body part (wrong-site procedures) are proving to be one of the most intractable patient safety issues. Despite years of effort at the state, national, and individual facility levels, these preventable events continue to occur.

Nationally, estimates of the annual incidence of wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient surgeries vary widely, in part because not all authors define these events—or even surgery itself—the same way, and may therefore be including or excluding a different set of events. Based on a review of the National Practitioner Data Bank and closed claims databases, Seiden and Barach (2006) estimated that wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient events may occur between 1,300 and 2,700 times per year. Kwaan et al. (2006) estimated that non-spine wrong-site surgeries occur at a rate of approximately one in 113,000 procedures.

The Joint Commission, which developed the Universal Protocol for prevention of wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient events, also collects data on the incidence of these events. According to The Joint Commission’s sentinel events database, 93 wrong-site procedures were reported during 2010, nearly double the 49 cases reported in 2004, the year that the Universal Protocol was implemented. Since Joint Commission data reflects incidents voluntarily reported by Joint Commission-accredited facilities, this is quite likely an under-representation of the incidence of these events; the increase, as well, could as easily be due to increased reporting as to rising incidence.

States that require hospitals to report wrong-site procedures as serious adverse health events provide another data source for estimating how often wrong-site procedures occur. Currently, roughly half of all states have reporting systems in place for serious adverse or sentinel events, although not all require reporting of wrong-site procedures. Here, too, it can be difficult to know how often these events occur; states vary in whether they require reporting of wrong-site invasive procedures or limit the reports to surgical cases, whether they require reporting from hospitals only or include other settings where invasive procedures take place, and whether they collect, publish, or release data by event type or year.

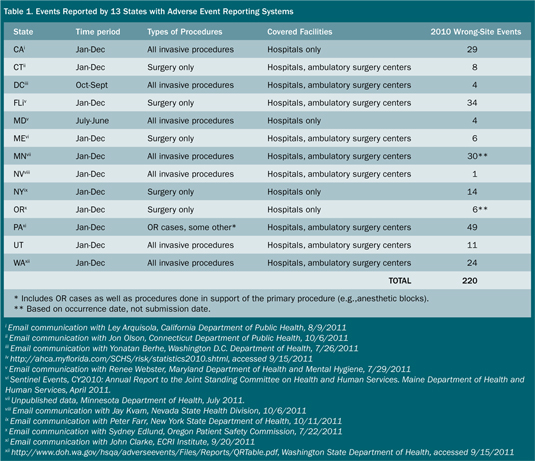

However, even with these many caveats, state reporting-system data indicate that wrong-site procedures happen much more often than had previously been understood. Of the 27 states with adverse event reporting systems, 13 were able to provide 2010 data for this paper; others either do not collect information on wrong-site procedures, were unable to separate these events from other surgical events, or could not release data. Their information on wrong-site procedures shows that in 2010 alone, more than 200 instances of wrong-site surgery were reported, more than double the Joint Commission’s figures (Table 1).

Wrong-Site Procedures in Minnesota

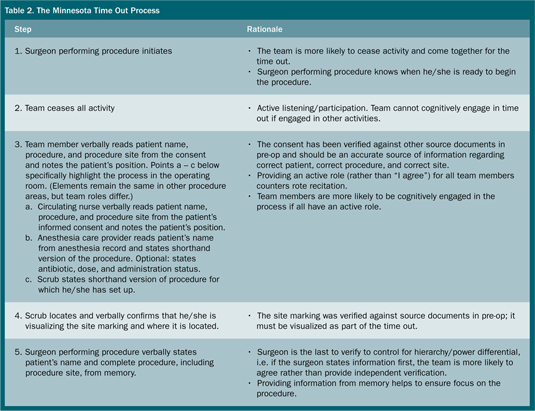

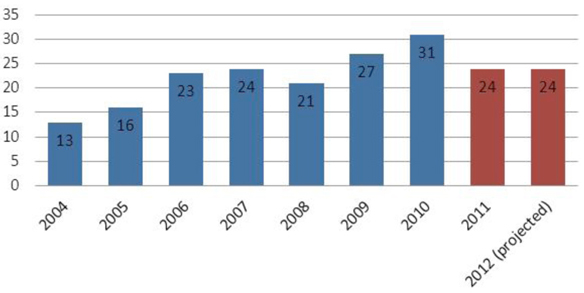

In Minnesota, hospitals have been required to report wrong-site procedures since 2003, as part of a law that also requires reporting of events on the National Quality Forum’s Serious Reportable Events list; ambulatory surgical centers have been required to report since 2005. During the first 7 years in which Minnesota’s reporting law has been in effect, a total of 1,403 events have been reported to the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH); 155 (11%) of those events were wrong-site procedures. The number of reported events in this category has increased across the first 7 years, rising from 13 in 2004 to 31 in 2010 (Figure 1). Four (3%) of these events resulted in serious harm to the patient, and 43 (28%) resulted in a need for additional treatment, in some cases a second corrective procedure.

Figure 1. Wrong-Site Procedures in Minnesota

Although much of the energy around prevention of wrong-site procedures is focused on the operating room (OR), it is important to remember that these events can occur in any setting in which invasive procedures take place. In Minnesota, more detailed information about the location of each wrong-site procedure has been collected since 2006. Since that time, roughly 45% of reported wrong-site procedures occurred outside of the OR—most commonly in interventional radiology (12%), anesthesia (9%), radiation therapy (9%), and the pre-operative area (3%).

Among their responsibilities under Minnesota’s adverse-health-event reporting law, hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers must provide detailed information about each reportable event to the MDH. Since 2006, these requirements have included questions about whether or not certain pre-procedure verification steps, such as site marking and a pre-procedure pause to verify correct patient, procedure, and procedure site (time out), were completed and whether specific aspects of an effective time out were in place.

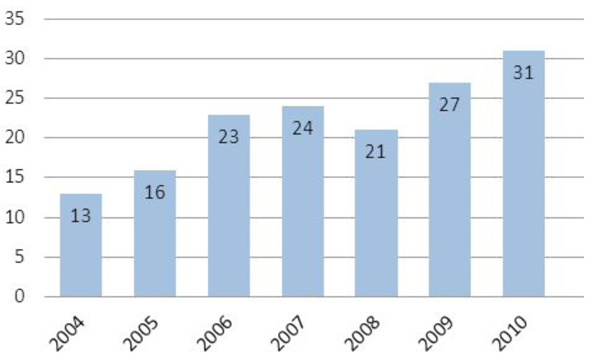

Data reported during 2007—the first full year in which information about pre-procedure verification steps was collected—indicated that in cases where wrong-site procedures took place, compliance with minimal standards for site marking and pre-procedure time outs was inconsistent, particularly outside of the OR. Overall, the site had been marked in just 54% of reported wrong-procedure cases, and a time out completed in only 51%. The differences between the OR and non-OR settings was pronounced, with wrong-site procedures that occurred in procedural areas far less likely to have included a site mark or time out (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Site Marking and Time-Out Compliance, 2007

While these data do not reveal how often these pre-procedure verification steps were completed in cases where a wrong-site procedure did not occur, they do provide some insight into the process breakdowns that occurred in cases where incorrect information about the procedure site was not caught in time to avert the wrong-site procedure. In 2007, 3 years after the launch of the Universal Protocol, it was evident that in Minnesota, site marking and time-out processes were not fully imbedded into the OR setting for all procedures. In non-OR settings, these processes had scarcely begun to become the norm.

More thorough analysis of the event data, including a review of the narrative root-cause-analysis findings, revealed that even in cases where the facility indicated that a time out had taken place, the process followed often bore few of the characteristics of an effective time out. In some cases, for example, the surgeon performing the surgical procedure had not been involved in the time out. Confusion about the appropriate way to conduct a time out, and about roles and responsibilities during the time out, was common.

Approach/Findings

Due to the continued problem of wrong-site surgery in Minnesota, beginning in spring 2007 the MDH and the MHA began working with human factors systems design researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Design in Health to observe pre-procedure verification processes in a variety of Minnesota hospitals, document weaknesses in current practices, and develop a more robust process based on human factors principles.

The human factors research team, led by Kathleen Harder, PhD (a paper co-author), conducted observations of a variety of 58 surgical procedures, of both long and short duration, from case set-up, before the patient arrived in the operating room, to case close, when the patient left the room following the procedure. Follow-up focus groups with surgical team members were also conducted.

The research team observed surgical procedures at eight facilities across Minnesota. MDH provided funding for observations at two large metropolitan hospitals and three smaller regional hospitals in greater Minnesota. The University of Minnesota Medical Center, Fairview (UMMC) provided funding for observations at their two metro hospitals and one sports surgery facility. Although the hospitals differed in size (ranging from small rural hospitals to large urban teaching hospitals), location (rural and urban were included), and patient populations, the observations revealed similar patterns of process breakdown across facilities and procedure type. Identified issues fell into three general areas: site marking, patient identification, and time out.

Site-Marking Issues

- Two observed procedures did not include a site marking; focus group participants at one facility noted that the site was sometimes marked in the OR rather than in pre-op.

- In one case, the procedure was changed while the patient was in the OR, and the site mark was not modified.

- It was reported that some surgeons marked the site from memory without reference to source documents; at one facility, site marking in the pre-operative area was delegated to a nurse.

- In one facility, the site was marked with a “yes” rather than with the physician’s initials; although the facility’s policy called for the physician’s initials in addition to a “yes,” this step was not completed.

- In one case, the site mark was not close to the procedure site; an upper arm was marked rather than a breast.

- At two facilities, site markings sometimes dissolved while the patient was being prepared for surgery.

Patient Identification Issues

- Only six cases included formal identification of the patient upon entry to the OR using the patient’s identification band.

Time-Out Issues

- In three cases, no time out took place; in a fourth case, a time out was not conducted for the second procedure in a dual-procedure case.

- In several cases, the circulating nurse attempted to call for the time out, but failed because team members did not cease their activity; in many others, team members did not verbally acknowledge the accuracy of the information provided by the circulating nurse or participate in the time out.

- At seven of the eight hospitals, at least one time out was done with the circulating nurse providing information from memory, rather than from source documents.

- In one case, the time out was not done until after the procedure had begun.

- In at least one case at each facility, the time out was conducted before the surgeon had gowned and scrubbed. In others, the time out was done with a resident or fellow present, and the attending surgeon was not briefed when he/she arrived. In one case, the time out was done with no surgeon present.

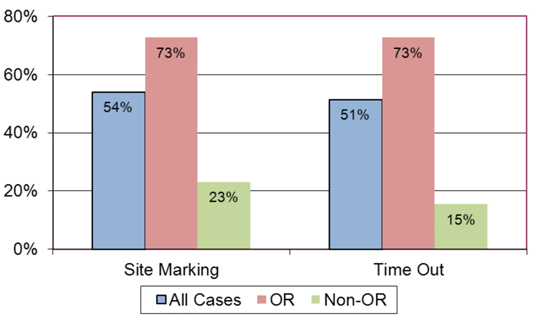

Based on these observations, the researchers designed a comprehensive pre-procedure verification process, the Safe Surgery Process. The comprehensive Safe Surgery Process was vetted with MDH, MHA, and UMMC to foster buy-in during the subsequent implementation phase. The steps in this process, and the rationale for each, are outlined in Table 2.

(Click here to view a Larger version in a separate window.)

Minnesota Time Out Process

The Minnesota Time Out process is a critical component of the full Safe Surgery Process. Each step of the time-out process has been designed based on human factors and cognitive science principles to create an effective time out that engages the full procedure team. The steps outlined below focus on the Minnesota Time Out process in the operating room; for procedures occurring in procedural areas, the five key steps remain the same but the team members involved in the time out will vary by procedural area.

Implementation/Dissemination

The Minnesota Time Out process was incorporated into statewide wrong-surgery prevention work that began in late 2007 through the Minnesota Hospital Association’s Safe Site campaign. This statewide collaborative of more than 100 hospitals and surgical centers focuses on the prevention of wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient events through the implementation of evidence-based best practices. Although progress was seen in the implementation of 53 recommended best practices—implementation improved from 59% in December 2007 to 95% implementation in December 2009—the root cause analysis data from reported events and discussions with hospitals revealed that all steps of the time out were not being followed consistently. In addition, clarity was needed for application in special circumstances such as an anesthesia block performed prior to a surgical procedure.

In late 2010, MHA convened a group that included MDH, the Minnesota Medical Association, the Minnesota Medical Group Management Association, the Minnesota Ambulatory Surgical Center Association, and MMIC Group, a medical professional liability insurance company. From this group, the Minnesota Safe Surgery Coalition was formed to address successes and challenges related to prevention of wrong site procedures and to brainstorm strategies for bringing together each organization’s resources and leverage to push for statewide implementation of best practices to prevent wrong-site and wrong-procedure adverse events.

During the spring of 2011, the Safe Surgery Coalition developed a plan for a 3-year campaign to eliminate wrong-site procedures; the activities of the first year would focus on ensuring that the Minnesota Time Out was conducted for every patient, every invasive procedure, every time. Each facility that signed up to participate in the Minnesota Time Out campaign (Figure 3) would be required to have its CEO sign off on this commitment. The coalition also sought to enlist professional associations as supporters of the campaign.

Figure 3. Minnesota Time Out Campaign Logo

To provide support to campaign participants, MDH, MHA, and the Center for Design in Health at the University of Minnesota collaborated on five training sessions around the state during the summer of 2011 to reinforce the key concepts of the Minnesota Time Out process and to provide rationale for the key concepts. The all-day training sessions included large and small group discussion, role-playing, and lecture components. Participants had an opportunity to hone their auditing skills by viewing videotaped time-out scenarios, which were developed using staff from a local simulation center, and using standardized auditing tools to check their knowledge of appropriate practices.

Participants in the campaign received materials and resources to support implementation of the time-out process: promotional posters, pledge posters for staff to sign, “I pledged” stickers, background documents and factsheets about the rationale for the time-out steps, talking points for leaders, sample policies and scripts, and a time-out video. To assist in engaging physicians in the process, MHA developed a “Physician Peer-to-Peer” DVD that featured prominent Minnesota surgeons talking about the importance, value, and simplicity of the Minnesota Time Out process.

The coalition will continue to support the campaign through activities such as monthly newsletters, template letters from partner organizations to their membership, and on-going recruitment of partners and provider organizations.

By the time the campaign kicked off on June 15, 2011—National Time-Out Day—119 facilities (93 hospitals and 26 ambulatory surgical centers) had made a pledge to conduct the five key steps of the Minnesota Time Out for every invasive procedure, every patient, every time. In addition, more than 15 partner organizations, including AORN Twin Cities, Minnesota Urological Society, Minnesota Academy of Ophthalmology, Minnesota Academy of Otolaryngology, Minnesota Society of Anesthesiologists, Minnesota Orthopaedic Society, Minnesota ACOG, and the Minnesota Organization of Leaders in Nursing signed up in support of the campaign.

Results

Since Minnesota began requiring reporting of wrong-site procedures in 2003, the number of days between events has generally ranged between 15 and 21, with an average of approximately six events reported per quarter.

During the first half of reporting in year eight, which began in October 2010, a wrong-site procedure was reported every 10 days, on average. Since recruitment and publicity for the Minnesota Time Out Campaign and Minnesota Time Out training began in April 2011, the average number of days between reported wrong-site procedures has increased to 18. The end of reporting for year eight saw a 23% reduction in statewide wrong-site procedures, from 31 in 2010 to 24 in 2011. The number of wrong site procedures for the ninth reporting year, which runs from October 7, 2011, through October 6, 2012, is projected to be 24 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Wrong-Site Procedures in Minnesota

Discussion

Minnesota’s experience in working to establish a consistent and effective time-out process as the statewide community standard in hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers has provided a number of key lessons about how to develop and implement process changes within and across organizations, as well as the sometimes hidden barriers to change that often derail safety campaigns. These key lessons can offer insight into how to successfully design not only a comprehensive safe surgery process, but also how to engage organizations and team members to successfully implement and sustain the key best practices that will have an impact on outcomes.

Lesson One: Details matter.

One of the fundamental lessons of this journey has been that it’s not about just doing a time out; it’s about doing a robust time out, every time. Over and over, Minnesota’s data and observations have shown that teams often believed that they were doing an effective time out, but in reality they were performing the time out in a rote manner, relying on memory, or not following all of the steps prescribed in their policies. Often the policies themselves may be unclear or insufficient, leading to multiple interpretations and inconsistent practice.

A time out that does not include full team participation and cognitive engagement of each team member is unlikely to do anything to prevent a wrong-site procedure from occurring; indeed, wrong-site procedures that occur after faulty, weak, or incomplete time outs feed the misconception that the time out is not effective in preventing these events. This can further undermine any future attempts to strengthen or revise the process. In order to be effective, time-out policies must include active participation by the full procedure team and be designed in such a way that passive responses (“I agree” or silence) are not sufficient.

Lesson Two: Focus on implementation as much as on process development.

One reason why teams persist in believing that they are conducting robust time outs, or marking sites correctly—when in fact they are not—is because of the lack of planning for roll out and implementation of the practice. Sufficient resources need to be devoted to critical roll-out and implementation steps, such as engaging physicians and other team members in the early stages, educating staff and physicians on the rationale for the practice change, supporting and coaching staff, and communicating with key stakeholders as the process moves forward.

This process does not end on the day that the new practice is launched. Organizations must establish clear goals for successful implementation and ensure that an individual or team is responsible for monitoring compliance and progress towards organizational goals. Regular observational audits in pre-op and the operating room are crucial to the process. Ongoing training and occasional refreshers may be necessary, along with making use of just-in-time coaching during observational audits. If the implementation process experiences roadblocks, process leaders should work with front-line staff to identify strategies for addressing and moving beyond these hurdles.

Lesson Three: Go with the (work)flow…and acknowledge our “humanness.”

While capable of remarkable feats, the human brain also possesses certain weaknesses inherent to all of us, regardless of our training or innate intellect. Humans forget things, make mistakes, downplay risks, and go on auto-pilot when performing routine tasks. These cognitive factors underlie many of the errors in the site-marking and time-out process that Minnesota’s observations uncovered. Examples include:

- Confirmation bias: Discounting information that disagrees with our preconceived notions, as when a site marking does not match an informed consent (Wason, 1960). In these cases, we may downplay the new information (site marking) and proceed based on what we already assumed to be true (informed consent).

- Risk perception: Assuming that errors or mistakes will happen to others and not to us (Slovic et al., 1982). This contributes to overconfidence and the notion that errors are due to insufficient skill or intellect on the part of those who commit them.

- Automated behavior: When we perform the same process repeatedly with no bad outcomes, whether driving to work each day using the same route, checking the “5 rights” of medication administration for every patient, or conducting a time out, we often start to pay less attention to the steps of the process. In our everyday life, this might mean arriving at work and not remembering the details of the drive; in the OR, this might mean going through the motions of a time out without paying attention to what is being said.

A strong process has to account for these issues and incorporate strategies to address these cognitive factors.

Lesson Four: Focus on key elements.

As facilities move forward with implementing a new process such as the time-out process, one of the most common struggles is to know where it is important to follow a prescriptive process and where there is room for modification to meet the specific requirements and workflow within an organization. Often, a well-intentioned team member may develop a tweak to a recommended process that substantially undermines its effectiveness, based on a lack of understanding of why each step was recommended.

For the Minnesota Time Out process, the focus has been on five key steps: 1) the surgeon performing the procedure initiates the time out; 2) the team ceases all activity; 3) the circulating nurse verbally reads the patient’s name, procedure, and procedure site from the patient’s informed consent; 4) the anesthesia care provider verbally reads the patient’s name and shorthand version of the procedure (and optional—to fulfill SCIP requirement—states antibiotic, dose, and administration status; the scrub verbalizes location of site marking and states procedure set up for; and 5) the surgeon performing procedure states patient’s name and complete procedure from memory. These five steps must happen for every procedure and every patient in the operating room.

However, there are other elements to the process that facilities can choose to adopt or to forego, including the use of a time-out towel or other visual indicator, and the inclusion of antibiotic dosage and timing as part of the anesthesia care provider’s role. Helping teams to understand what the crucial elements of any process are, their rationale, and what may be optional will increase their odds of success.

Lesson Five: Align activities with other initiatives.

Many hospitals are now adopting a surgical or procedural checklist, such as the WHO surgical safety checklist, as a tool to ensure that all time-out and other pre-procedure steps are followed. The WHO checklist describes a set of key elements that should be completed prior to surgery, including a time out, but provides flexibility to facilities in determining their process based on their workflow. Additions or modifications based on local practice are encouraged.

The WHO checklist’s flexibility allows it to be easily adapted to work with a more prescriptive process such as the Minnesota Time Out. A number of Minnesota hospitals have implemented the WHO checklist and Minnesota Time Out together, and have found that the five key elements of the Minnesota Time Out process can be effectively incorporated into a surgical or procedural checklist. This format provides flexibility to adapt to work flow pre- and post-procedure, yet provide structure for the time period just prior to incision or procedure start when the focus needs to be on verifying the correct patient, correct procedure, and correct site. By integrating the Minnesota Time Out with other efforts that are already underway, the implementation process can be streamlined, often making it easier to get buy-in from administrators and surgeons.

Lesson Six: Persistence is key.

Changing a process such as the time out across an organization or across a state is not only a process change: it is adaptive change, and in many ways a change in organizational culture. Processes do not exist in a vacuum; many of the site-marking and time-out workarounds that develop within a facility are in response to issues related to workflow, physician preferences, time pressures, power differentials among team members, and between front-line staff and organizational leaders, as well as communication patterns. Attempts to change the time-out process often lead to deeper discussions about how current practices have developed and why they exist.

Adaptive change typically does not happen in a short period of time. The Minnesota Time Out work has evolved over a period of years, from its origin in early analysis of reported adverse health events and establishment of the Safe Site campaign in 2007, through the development of the Minnesota Time Out process in 2007–2008, to the current activities of the Minnesota Safe Surgery Coalition. Nearly 5 years after the work began, the implementation is not yet complete. In the summer and fall of 2012, the University of Minnesota again conducted observations in hospitals around the state to assess adoption and successful, consistent implementation of the Minnesota Time Out; preliminary findings show that some facilities still face challenges in achieving all steps of the process consistently.

In order to realize and hardwire successful change, staff members, physicians, and leaders need to support the process in the long term. For executive and clinical leaders, this means providing necessary resources to campaign leaders, being a visible source of support for the campaign, and recognizing individual and organizational successes. It also means that administrators must be proactive in setting and communicating expectations to physicians and staff, so that circulating nurses or other staff are not put in the position of trying to enforce policies with physicians and staff who may not want to modify their practice. Administrators must also support front-line staff who come to them with issues related to noncompliance, particularly by physicians, and ensure that expectations are upheld. Front-line staff and campaign champions need to understand the long-term nature of the issue as well and need to have support throughout the process in order to maintain their energy, recognize their progress, and respond to issues as they arise.

Conclusion

The Minnesota Time Out process, developed by human factors systems design experts, and now the community standard throughout Minnesota, is just one piece of the comprehensive Safe Surgery Process that includes pre-operative verification, team briefings and debriefings, and other important safety steps. Its implementation in facilities across the state has been a multiple-year process involving numerous stakeholder organizations all providing support and resources. Through this collaborative process, practice and outcomes are beginning to change in Minnesota, offering a model for other states to consider as they continue to work towards the elimination of these serious preventable events.

Diane Rydrych is director of the Division of Health Policy at the Minnesota Department of Health and manages the Minnesota Center for Health Statistics. For the last 6 years, she has led the department’s work on patient safety, including directing Minnesota’s statewide adverse health events reporting system and working with hospitals and surgical centers around the state to develop and implement best practices for prevention of adverse events and patient harm. Rydrych has a master’s degree in public policy from the Humphrey Institute at the University of Minnesota. She may be contacted at Diane.Rydrych@state.mn.us.

Julie Apold has been the director of patient safety for the Minnesota Hospital Association for the past 7 years, managing patient safety and quality activities. She collaborates with the Minnesota Department of Health to support Minnesota Adverse Health Event Reporting Law activities; manages the adverse event reporting registry; and works with hospitals and the Registry Advisory Council to provide guidance on fulfilling reporting requirements and analyzing events for trends, safety alerts, and improvement opportunities. Apold is currently managing five state-wide collaboratives to address the top reported adverse event categories – pressure ulcers, surgical safety, retained objects, and falls.

Kathleen Harder is director of the Center for Design in Health at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. In her research program, she applies her expertise regarding the strengths and weaknesses of human information processing to design systems that facilitate better human performance and reduce errors. Dr. Harder designed the Safe Surgery Process described in this article. In 2009, the Joint Commission approved the Safe Surgery Process as an alternate universal protocol in the State of Minnesota. The Safe Surgery Process has been implemented in a number of hospitals in Minnesota and is undergoing implementation in other hospitals in Minnesota and the United States.