Preventing Falls: The A-B-C Approach

May / June 2012

![]()

Preventing Falls: The A-B-C Approach

Little kids play at falling down. When people are a bit older, falling is avoided—unless they are into tumbling or martial arts! And once they reach the level of senior citizen, falling becomes potentially fatal. According to a literature review by Clyburn and Heydemann (2011), statistics show that falls are the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries to older people in the United States. Each year, more than 11 million people 65 and older suffer falls.

Little kids play at falling down. When people are a bit older, falling is avoided—unless they are into tumbling or martial arts! And once they reach the level of senior citizen, falling becomes potentially fatal. According to a literature review by Clyburn and Heydemann (2011), statistics show that falls are the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries to older people in the United States. Each year, more than 11 million people 65 and older suffer falls.

Clyburn and Heydemann add that as many as 20% of hospital inpatients will fall at least once during their stay. These falls are considered preventable by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid; therefore healthcare facilities are held accountable for the costs of treating any resulting injuries. What can be done to prevent falls? Are we doing all that we can?

First is A.

If we take an A-B-C approach, A is for Administration. Administration is responsible for developing policies to prevent falls and those in the unit are the ones who implement those policies. Jim Hendrich, president of AHI of Indiana and who, with his wife Ann Hendrich, BSN, PhD, vice president, clinical excellence operations, Ascension Health, is a well-known advocate for fall prevention, explains, “One hurdle that must be overcome is how to train leadership with the skills needed to determine what is referred to as ‘Common Causes’ for falls. Each patient is unique, but as part of any on-going analysis of fall data, administrators should be able to identify certain trends for further discussion by the organization to determine where improvement can occur.” Hendrich further explains, “First, the problem has to be identified; second, awareness of the problem has to be communicated effectively; third, actions have to be taken—and this step incorporates a willingness to adopt change—and the commitment has to be there to see the process completed. And fourth, there has to be sustaining of the improvement process to accomplish meaningful changes—hopefully for the better.”

A is also for Assessment. Donna Shaw Pope, risk manager at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, Rahway, New Jersey, notes, “We all start with the assessment and then the plan of care. It is really important how well that’s done. Then, when it’s handed off to different units, it should be adjusted and updated. If they’re in the acute care unit, it’s done every 12 hours. If there is a fall, it has to be readjusted again. Depending on how well you do that assessment, taking all these factors into consideration will help to prevent falls. It’s critical that you do that assessment accurately and thoroughly.”

Developing assessment criteria can be tricky. Francene Stauber, assistant director of rehabilitation services at South Nassau Communities Hospital in Oceanside, New York, agrees:

Many of our patients are elderly, they have multiple co-morbidities, and they have a lot of the factors that make them a very high risk of falls. What we did was create a weighted screening tool to determine, based upon our population, which patients that we admit are at a high risk for falls. From that screening tool and from that identification of patients that are at high risk, we implemented a program to provide the interventions that we felt would prevent these people from falling, or at least decrease the modifiable risk factors. It incorporates all of the evidence in the field and also data from a post-review of the falls that we incurred. Were the patients all over 65 years of age? Were they on four or more medications? Were those medications hypnotic or psychotropic medications?

Which brings us to B.

B can stand for many things—Balance, for example. At South Nassau Communities Hospital Home Care, Nancy Helenek, administrative director of the Care Continuum, notes, “Our hospital implemented the Hendrich Fall II Assessment, and that gives us information when the patient goes into home care. Then, besides the home-safety assessment and medication reconciliation that the nurse would perform on admission, we do an assessment of the patient’s balance using the Tinetti Balance Assessment Tool. In addition, we do a range-of-motion manual muscle test to determine strength and balance. We ask about any history of falls or near falls.”

More information on the Hendrich Fall II (H2) Assessment can be found online at http://www.ahiofindiana.com while a copy of the Tinetti Balance and Gait Assessment Tool, developed in 1986 by M.E.Tinetti, is found at http://www.ohsu.edu/sgimhartford/toolbox/TinettiBalanceAndGaitEvaluation.pdf among other locations.

While the assessment of the physical condition of the patient gets to the core of many falls, Barbara Resnick PhD, professor of nursing at the University of Maryland, wants caregivers to focus more on the person’s functions and to optimize those functions in all routine care.

We’re going to optimize how much the patient does. If that person is totally dependent because of multiple strokes—or even end-stage dementia—then we’ll do what we can so the person at least has range-of-motion. If the person is independent, then we’re going to optimize the amount of physical activity they engage in and try to get them up to 30 minutes a day of moderate physical activity. It all depends on the individual, but in all cases, we’re thinking about optimizing function and physical activities rather than just doing the task for them.

In this method, you establish goals with the patient. Resnick continues,

We work with those individuals to find out what it is they want to do, what’s important to them, and we also spend a lot of time identifying the kinds of things they did in their earlier lives. We use those factors to integrate physical activity. For example, if somebody was a policeman, we might have him “walk a beat.” If they were a nurse, they help us make rounds.

Another B is Bed. Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital’s Robert Pisko, manager of occupational safety, says, “We’re working with Kerr Medical’s wireless alarm bed pad, chair pad, and floor pad. When the patient is on the bed and moves off the bed, it will automatically alarm right to the nurse station. The chair pad does the same thing. And if the patient touches the floor, the sensor will go off on the floor pad and that will ring to the nurse station as well.”

At McNeal Hospital in Chicago, Maria Hill, RN, vice president of patient quality and safety tells us, “We implemented beds in a low position and have fall alarms—a pad on the bed or on a chair that recognizes change in pressure. We’re looking at some of the newest technology that’s been developed that would give us earlier indication of the patient’s agitation so we can be alerted and can check on them and assist them if they need to get up.”

The Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation (CNR) in Brooklyn, New York, puts an overlay with built-in side guards on the mattresses of patients who tend to get out of bed unassisted. The raised ridge helps the patient recognize the edge of the bed and gives staff additional time to respond to bed alarms. Their nursing staff also began assessing pain differently by revising the scales used to measure discomfort for many of the cognitive-impaired residents with a history of falls. In some cases, medications were changed or discontinued. These and other changes helped them decrease falls by 53% in 2011.

In Lincoln, Nebraska, Nicole Livermore, nurse educator for oncology at St. Elizabeth Hospital recalls, “We were having about one fall a month where a patient had disconnected their bed alarm because it’s not that hard to figure out—people are pretty clever! So they would get up without us knowing. A representative of Stanley Healthcare Solutions came and showed us their new pressure pads that the patient would lay on and the minute they try to get out of bed, it goes off. There’s no way for them to bypass it. Even if they unhook it from the wall, it still alarms.”

St. Elizabeth implemented the monitor and pad system and then did a big education campaign for their staff. “We instructed them about having to answer the alarms and what you do when you hear them,” Livermore says, “and we tried to get it out to everyone, not just clinical staff but environmental services as well, so they all knew that it meant there was somebody at risk for getting injured.”

Another facility using the Stanley Healthcare system is Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, Missouri. Eileen Costantinou, practice specialist, explains,

The technology will immediately notify the nurse’s pager when a patient is attempting to get out of bed, when the bed is not low, or if the side rails are not locked in place. We have used the Bed Check device for many years, so it has been a solid component of our fall prevention program. In fact, in almost all of our inpatient units, the monitors are mounted on the wall above the patient bed. We have not utilized them to their fullest extent however—meaning the reporting features—we simply use them as an alarm.

B can also be for Bathroom. Getting up from a hospital bed is, more often than not, for a trip to the bathroom. With decreased capabilities from medication or surgery, falls can result. At Palomar Health, San Diego, California, Jackie Close, RN, PhD, notes, “There are two classes of patients most likely to incur falls: the middle aged male who ‘doesn’t need help,’ and the elderly patient. Sometimes we have patients with a brain injury of some sort and they don’t comprehend their environment and are very impulsive. We do our absolute best to keep them safe with all the fall prevention interventions as well as family assistance and personal observation assistants when necessary.”

McNeal Hospital’s Hill adds, “We learned that we have to, in effect, do continuous rounds, especially on the night shift. We found that late in the evening and at night, people are disoriented because they’re not in their normal environment.”

Kim Jordan, rehabilitation manager at Greensprings Long Term Care in Springfield, Virginia, acknowledges the importance of the environment:

We have looked at alternative flooring on some of our floors, primarily in the bathroom area and also some dining areas, to put in nonskid or more slip-resistant floor surface. We’ve looked at the amount and quality of the lighting, the brightness of the lighting, and at some automatic night lights including movement-sensing. When somebody is getting up and out of the bed, instead of having to turn on the light, that light automatically comes on to create a pathway to the bathroom.

And then there’s C.

| |

|

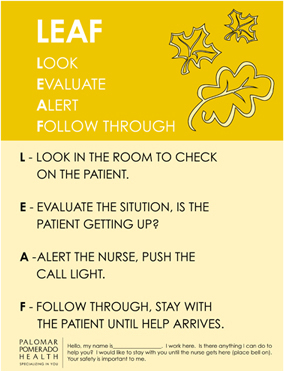

| Figure 1. Palomar Health uses “falling leaves” as a graphic element to highlight fall prevention measures. |

Finally, we come to C. One of the simplest approaches to awareness is to Color-Code the level of risk that a patient has to falling. At Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, New York, Marie Spenser, RN, PhD, the chief nursing officer, says, “We got rid of the common red-yellow-green codes: either you’re at risk or you’re not at risk for falls. Once you’re assessed to be at risk you get a yellow wristband that alerts everybody. We put a yellow placard on the back of the patient’s wheelchair, and if that placard has a blue dot, everybody knows that person is never to be left unattended. If a staff member sees that patient in the hallway and there’s nobody near them, they stay with that patient to make sure they are safe. I think this heightened awareness extends throughout the whole building.”

At Palomar Health, Close reports on their new building that will open later in 2012. “Our work stations will be outside of the patient rooms as there will be no central nursing stations. This will put the nurses closer to their patients to add to safety and fall prevention. Rooms will have yellow lights above their doors and if the patient is a fall risk, the yellow light will be illuminated. This will alert everyone that this patient is a fall risk. We will continue using pictorial fall leaves, just another added feature for patient safety.” The “fall leaves” she refers to is a small design of autumn leaves that is placed near the entrance of an at-risk patient’s room.

More Letters

Color coding takes many forms and, in one case, it is another B—for Booties. Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital issues bright yellow socks (with sole grips) to patients who are deemed high risk for falls. This way, all staff members know which patients will need extra attention. In fact, in order to encourage staff buy-in, the president and CEO modeled the socks in educational posters and flyers as part of an internal awareness campaign.

Which points out one of the greatest asset in fall prevention that combines A, B, and C: Administration Buy-in and Champions. Determine who in the organization can act as a champion for fall prevention; get the troops at all levels involved, from administration to patient and family to elevator operators and food delivery people.

Then get facility management, environment designers, and executives invested in preventing falls. As Drew Troyer, principle at Sigma Reliability Solutions, Tulsa, Oklahoma, states, “Falls are not restricted to patients, as anyone who works in healthcare knows. Slip and fall injuries are a major concern for risk managers in hospitals. The U.S. Bureau of Labor reports that there are 38.2 slip and fall accidents that lead to lost-time accidents for every 10,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees in the healthcare industry—nearly double the rate for all other employers.”

Statistically, slip and fall accidents are costly in terms of direct patient injury cost, lost work time, pain and suffering, prolonged patient recovery and, in some cases, legal action. The Centers for Disease Control suggests that 30 to 48% of falls result in a serious injury and cost between $4,200 and $19,400 per event. In some instances, these accidents lead to fatality.

Moreover, insurance to cover hospital-acquired conditions can get a little dicey. Troyer explains, “Managing the risk of slip and fall accidents must be a high priority in the healthcare industry. The Joint Commission has identified fall accidents as a major risk in assuring patient safety and offers useful advice for preventing them.”

“Unfortunately measuring the slip-resistance of the walking surface itself, a must-have component of your slip and fall risk management system has, up until now, been a weak link in the chain of control. Fortunately, new American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards for auditing and measuring the slip-resistance of pedestrian walkways are adding science and control to the risk manager’s arsenal of defenses against slip and fall accidents in healthcare settings.”

He concludes, and we concur, “Let’s put these ideas to work!”

Tom Inglesby is an author based in southern California who writes frequently about medical technologies and improvement strategies.