Preventing Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections in Adult ICUs: A Three-Pronged Approach

By Marcie Metroyanis, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, and Catherine Gargan, RN, CCRN, CNRN

Introduction

Approximately 2 million hospital-acquired infections (HAI) occur in the United States annually (Lillis, 2015). Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) are the most common HAI and are associated with complications such as morbidity, mortality, patient discomfort, unnecessary antimicrobial treatment, increased length of hospital stay, and increased costs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Lillis, 2015; Meddings, Krein, Fakih, Olmsted, & Saint, 2013; The Joint Commission, 2011). A CAUTI may be caused by a urinary catheter as bacteria enter the bladder during insertion, either through the urinary catheter lumen or from outside the urinary catheter. Patients are diagnosed with a CAUTI if they have a positive urine culture more than 48 hours after a urinary catheter placement. A patient diagnosed with a CAUTI may not be treated if he or she is asymptomatic; however, a patient who is symptomatic is treated with antibiotics (Imam, 2019). If antibiotics are necessary, proper consideration of antibiotic use is essential to slow the development and spread of antibiotic-resistant organisms, which can be difficult to treat (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019).

Based on the severity and urgency of preventing CAUTIs, the University of Rochester Medical Center coordinated a project team to collect and analyze CAUTI data and further identify prevention techniques in adult ICUs. The CAUTI project team was comprised of nursing leaders, ICU nurse champions, and a physician liaison.

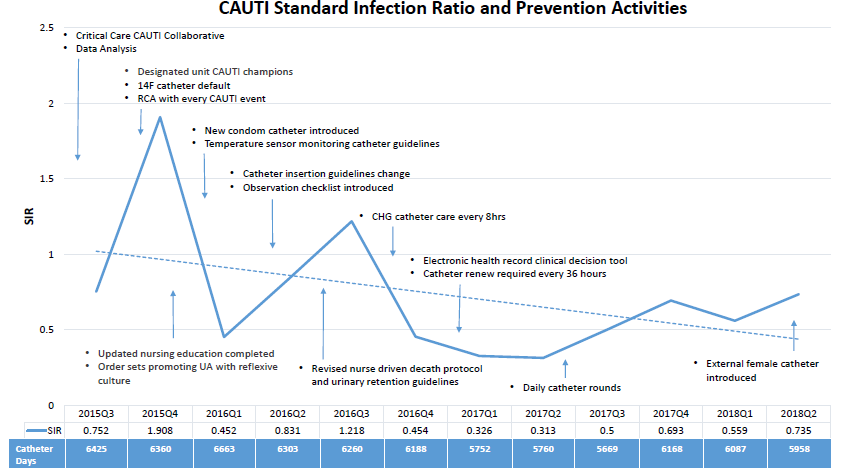

From July 2015 through December 2015, CAUTI occurrences began to trend upward in adult ICUs. The project team participated in the University Healthcare Consortium (now Vizient, Inc.) CAUTI Collaborative to network with healthcare facilities nationwide and implemented three initial prevention strategies to begin the process (see Figure 1):

- Using a #14F urinary catheter as a default to prevent unnecessary use of a larger urinary catheter (Imam, 2019)

- Performing a root cause analysis (RCA) for each CAUTI occurrence

- Implementing a process for urinalysis with reflective culture

CAUTI project team

Collaboration is essential when addressing patient outcomes, including practice changes among frontline nursing staff and providers. The project team focused on key stakeholders, anticipating that these stakeholders would facilitate changes in the workplace culture from “the way we’ve always done things” to safer practices that may have been considered inconvenient in the past. To steer the project goal of reducing CAUTIs, the project team referenced the Guideline for Prevention of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), which served as a valuable tool (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a). HICPAC CAUTI prevention guidelines recommended addressing the following in relation to urinary catheters: appropriate use, aseptic insertion, and proper maintenance (Parker et al., 2009). These guidelines and recommendations led to the development of a “three-pronged approach” to reduce CAUTIs in adult ICUs.

Project team analysis

The nurse champions continued to monitor each CAUTI occurrence and perform RCAs for the duration of the project, and the information was regularly shared among the project team. The data revealed common risk factors corresponding with the HICPAC guidelines along with additional risk factors. Baseline practices were also compared to best practices according to literature and information shared during the collaborative. The project team concluded the following could place a patient at risk of developing a CAUTI:

- Indication for urinary catheter use

- Urinary catheter insertion technique

- Urinary catheter maintenance

- Assessment of continuous urinary catheter use

- Urgency of urinary catheter insertion

- Use of alternative methods to replace use of a urinary catheter

- Available urinary devices

- Urine culture guideline compliance

- Appropriate use of urinary retention guidelines

- Use of a urinary catheter nurse-driven protocol

- Appropriate urinary catheter size

- Urinary catheter temperature sensor monitoring

Based on these risk factors, the project team was able to formulate CAUTI prevention implementation strategies.

Implementation

Appropriate use of urinary catheters

Often, urinary catheters are used for patients who may not need them. When there are gaps in standard practice, inconsistencies may occur when determining appropriate indications for urinary catheter use. Physicians, nurses, and other providers frequently find themselves focusing their priorities on more acute issues. In addition, it may be more convenient for a patient to have a urinary catheter due to the time and effort involved in accommodating bathroom needs. To change the culture of common practices, it is important to raise awareness of the complications associated with urinary catheter use. This can occur by sharing data with physicians and nurses, providing education, and engaging key stakeholders in preventive strategies.

To address urinary catheter use according to an appropriate indication, the project team physician worked with an attending physician group to develop a clinical decision tool in the electronic health record. The tool was designed to provide guidance to ordering providers when determining the necessity of a urinary catheter. The clinical decision tool is a standard urinary catheter order set that inhibits a provider from entering an order unless one of the following indications is determined:

- Acute urinary retention or bladder obstruction

- Hourly urinary output in critically ill patients

- Sacral or perineal wounds

- Prolonged immobilization, excluding chemical paralysis and sedation

- End-of-life comfort care

- Select surgical procedures

If the provider determines urinary catheter use is indicated, a list of non-catheter options will populate, allowing the provider to consider any possible alternatives to use of a urinary catheter. Options vary according to each indication, possibly including interventions such as the use of tamsulosin (Flomax®) or finasteride (Proscar®), a bladder scan, an external catheter device, a bedside urinal, a bedside commode, a straight catheter protocol, and/or daily weight measurements. If an alternative is not appropriate and the patient meets the criteria for a urinary catheter, the provider enters the order and is required to reassess the catheter use every 36 hours, then renew or discontinue the order as needed.

Urinary catheter insertion

Next, it was important to consider the potential infection risk related to the urinary catheter insertion procedure. The project team created a new standard for urinary catheter insertion that was designed to ensure sterile technique during the procedure. This new standard involved not only the urinary catheter insertion process but also an observation process, including a checklist as well as donning personal protective equipment. The standard requires a minimum of two nurses, including the nurse who is inserting the urinary catheter and the observer. If additional assistance is needed to position the patient for the procedure, a third staff member (licensed or unlicensed) provides the support. In addition to the observation checklist, all participants are required to don a surgical mask and cap. The project team is aware that this step will not necessarily prevent a CAUTI; however, it was included to communicate the importance of sterile technique. Once these components are established, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) peri-care is used prior to beginning the insertion procedure, as opposed to the previous standard of soap and water.

During this process, the observer follows each step on the checklist. These steps include confirming a provider order is present, performing hand hygiene, donning a surgical cap and mask, performing CHG peri-care, confirming a sterile hand is maintained, and ensuring the urinary catheter remains sterile. The procedure is followed by maintenance care such as applying a catheter securement device, placing a drainage bag below the bladder, and ensuring there are no kinks or obstruction in the tubing.

Urinary catheter maintenance

The final component of the three-pronged approach involves performing CHG urinary catheter care every eight hours. Originally, requirements for urinary catheter maintenance involved daily use of soap and water. Literature reveals that CHG is safe to use (Fasugba et al., 2019) for urinary catheter care, and although there is a lack of evidence to suggest CHG prevents CAUTIs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a), the CAUTI project team determined that this practice could improve urinary catheter maintenance care. The process for CHG urinary catheter care includes cleaning the urinary catheter insertion site with a CHG cloth every eight hours and after each incontinence episode. The catheter is cleaned using an additional CHG cloth, starting at the insertion site and cleaning down the catheter at least 6 inches.

Nursing and provider engagement

The project’s success was due to the active involvement of the CAUTI champions and physician liaison, with nursing leadership support. The project team was committed to CAUTI prevention efforts, and all members were highly engaged throughout the process. The physician liaison also collaborated with and engaged other providers to develop the electronic urinary catheter decision tool. Furthermore, the CAUTI champions assumed responsibility for continuing CAUTI prevention efforts, and compliance was achieved by engaging key stakeholders. This level of engagement and success also promoted workplace satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment.

Conclusion

There is no single solution for CAUTI prevention; therefore, every possible risk factor must be considered. Addressing all potential causes and implementing best practices provides an increased chance of reducing CAUTIs. The project team’s three-pronged approach involves strategies currently not found in literature as a bundle. In addition, the project team followed through with implementing the changes necessary to reduce CAUTIs.

Marcie Metroyanis is an assistant quality officer in the quality & safety department at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Catherine Gargan is an assistant nurse manager in the neuromedicine ICU at University of Rochester Medical Center.

Acknowledgments:

Wendy Schramm, BSN, RN, CCRN; Kimberly Brogan, RN, CCRN; Sara Asenato, BSN, RN; Deena Felix, BSN, RN; Paritosh Prasad, MD, DTM&H; E. Kate Valcin, RN, MSN, NEA-BC; Pat Reagan Webster, PhD, CPPS; Lara Elizabeth, BSN, RN; Laura Fitzgerald, BSN, RN; Paige Strassner, BSN, RN; JoAnn Eldred, MS, RN, CCRN

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019a). Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/CAUTI/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019b). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [CAUTI] and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection [UTI]) and other urinary system infection [USI]) events. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscManual/7pscCauticurrent.pdf

Fasugba, O., Cheng, A. C., Gregory, V., Graves, N., Koerner, J., Collignon, P., … Mitchell, B. G. (2019). Chlorhexidine for meatal cleaning in reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: A multicentre stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 19(6), 611-619.

Imam, T. H. (2019). Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs). Merck Manual Professional Version. Retrieved from https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/genitourinary-disorders/urinary-tract-infections-utis/catheter%E2%80%93associated-urinary-tract-infections-cautis

The Joint Commission (2011). Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. R3 Report. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/R3_Report_Issue_2_9_22_11_final.pdf

Lillis, K. (2015). Device-associated infections: Evidence-based practice remains the best way to decrease HAIs. Infection Control Today. Retrieved from http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/2015/04/deviceassociated-infections-evidencebased-practice-remains-the-best-way-to-decrease-hais.aspx

Meddings, J., Krein, S. L., Fakih, M. G., Olmsted, R. N., & Saint, S. (2013). Reducing unnecessary urinary catheter use and other strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections: Brief update review. In Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Ed.), Making health care safer II: An updated critical analysis of the evidence for patient safety practices. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133354

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). Overview: Health care-associated infections. Health.gov. Retrieved from https://health.gov/hcq/prevent-hai.asp

Parker, D., Callan, L., Harwood, J., Thompson, D. L., Wilde, M., & Gray, M. (2009). Nursing interventions to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Part 1: Catheter selection. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 36(1), 23-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.WON.0000345173.05376.3e