Online Support for IV Drug Administration: Evidence-Based Nursing at WakeMed Health & Hospitals

March / April 2007

Online Support for IV Drug Administration

Evidence-Based Nursing at WakeMed Health & Hospitals

![]()

WakeMed Health & Hospitals has its sights set on being a leader in patient safety and quality care. And, like any leader, WakeMed is continuously looking for innovative systems and workflow solutions that give clinicians the information they need to provide high quality, evidence-based care.

Quality and Patient Safety: A Healthcare Priority

WakeMed, one of the first hospital systems in the country, is a private, not-for-profit healthcare organization based in Raleigh, North Carolina. The system comprises a network of healthcare facilities throughout Wake and Johnston Counties, including a 515-bed tertiary referral hospital, a 114-bed full-service hospital, a 68-bed rehabilitation hospital, two full-service clinics as well as two short-term, skilled-nursing and outpatient facilities. Specialty service areas include cardiac care, women’s and children’s services, physical rehab, emergency and trauma, orthopedics, neurosciences, and home care. WakeMed is the only hospital in Wake County and one of only three in North Carolina designated by the Leapfrog Hospital Quality and Safety Survey as one of the 50 Top Hospitals in the country.

WakeMed’s premiere Heart Center completes more than 20,000 total cardiac procedures and performs more than 1,000 open-heart surgeries each year, more than any other hospital in the state. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina named it a Cardiac Center of Excellence, and it is one of nine North Carolina hospitals included in UnitedHealthcare’s Premium Cardiac Specialty Center Network. One of only six Level 1 Trauma Centers in the state, the WakeMed Trauma Center had 1,788 trauma admissions in 2005.

![]()

IV Meds: The Best of Drugs, the Worst of Drugs

Prior to implementing its new point-of-care medication system, WakeMed’s nurses made clinical decisions about intravenous medications the tried and true way: with paper. They manually updated document printouts of dilution and administration instructions for more than 200 intravenous drugs, risking lags in updates and inconsistencies typical of paper-based environments.

Ensuring that accurate information is available quickly is especially important at WakeMed because of its high volume of intravenous drugs. Compared with other routes of administration, the intravenous route is the fastest way to deliver fluids and medications throughout the body. And speed is particularly important in cardiac emergencies, where the rapid administration of thrombolytic drugs and anticoagulants is critical (NHLBI, n.d.); and in trauma situations with their higher level of acuity patients. Indeed, the very things that made the organization exceptional — cardiac and trauma care — made critical WakeMed’s need to manage IV medications effectively.

The sheer number of IV meds — individually and in combination — can hinder nurses’ ability to administer them with both speed and accuracy. According to the leading authority on IV compatibility, there are more than 600 parenteral drugs and solutions and more than 50,000 possible combinations (Trissels.info).

In addition, dosing for IV meds is more complex than oral meds. In a recent study of more than 70,000 IV-related medication errors, as many as 5% resulted in harm — greater than the percentage of overall errors resulting in harm (Hicks & Becker, 2006). An FDA study of adverse drug events (ADEs) supports these findings, pointing to human factors as the most common causes of medication errors and miscalculation of dosage or infusion rate and drug preparation as the most common of these human factors (Thomas, et al., 2001). Indeed, among ADEs, IV-related errors have the greatest potential to harm patients as evidenced by the following findings:

- 35% of all medication errors that result in significant harm are the result of IV pump errors (Tourville, 2003).

- 40% of patient deaths from ADEs are due to administration of the wrong dose (Phillips, et al., 2001).

- 16% of patient deaths from ADEs are due to administration of the wrong drug (Phillips, et al., 2001).

In 2003, WakeMed took the first step to improve this paper-based system by making the documents available online on the hospital’s intranet, which nurses accessed via terminals at the nurses’ stations. In addition, the hospital gave nurses online access to evidence-based clinical decision support tools for IV guidelines and compatibility data, drug and disease information, as well as patient education materials. Nurses sometimes found the sheer volume of the available data intimidating and difficult to navigate. An online inquiry brought back more information than the nurse needed.

Moreover, going online meant going to the nurses’ station, which meant leaving the bedside. Nurses wanting to provide quality care will readily go to extremes to put information where they can get to it — easily — when they need it. Therefore, as before, nurses simply printed the information and created their own guidelines, replete with strikethroughs and margin notes.

With so much potential for error and so much potential harm from that error, WakeMed needed a way to give nurses accurate, comprehensive infusion drug knowledge, consistent across both the organization and the scope of care in a form portable to the bedside.

![]()

It’s All About Accessibility

Centrally updated computerized systems have the proven advantage of limiting the availability of outdated references and providing timelier information updates (Levine, et al., 2001). The ideal system should provide:

- Current references that are easily accessible when and where needed — namely, wherever medications are prescribed, prepared, monitored, and administered — and as a pocket-sized version (hardcopy or electronic) for convenient carrying (Levine, et al., 2001).

- Up-to-date, computerized drug databases and Internet access to medical information, texts, and publications (Levine, et al., 2001).

- Accepted guidelines for appropriate use of medications (i.e., instructions for administration or infusion methods and usual doses), precautions, drug-drug and drug-nutrient interactions, potential adverse effects, and patient information and instructions (Gupta & Waldhauser, 1997).

- Institution-specific guidelines including standardized doses accepted by the institution, standardized concentrations available within the institution for intravenous and oral medications (Gupta & Waldhauser, 1997). These guidelines should also reflect hospital policy (e.g., prescription and administration restrictions).

The ideal system for WakeMed was a new online resource for intravenous medications that nurses could use to research and administer IV drugs — quickly, accurately, consistently.

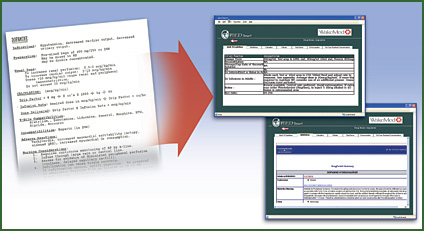

In late summer 2004, pharmacy collaborated with information services (IS) to develop and implement a dedicated, online portal they call MED Smart, which provides IV guidelines, comprehensive IV compatibility data, detailed drug information, and a technology tool to make it all accessible. MED Smart includes:

- WakeMed’s intravenous guidelines: Both standard and hospital-specific procedures and policies, comprising the information in — and replacing — the paper-based drip notebooks.

- Links to hospital policies and order sets specific to each medication when available.

- A new online drip calculator: For many medications, nurses can enter whether they want a standard, double, or maximally concentrated preparation and the patient’s name and weight. The calculator uses this information to determine the accurate IV dosage for the patient, creating a one-page drip factor calculation nurses can print and use at the bedside to monitor infusion rates and calculations for each patient.

- Infobutton access to detailed drug databases. Infobuttons, which are preformulated search strategies embedded as links in the clinical information system, give users dynamic access to information relevant to particular clinical tasks (Mariglia, et al., 2006). Wake Med’s infobuttons comprise integrated search and retrieval technology that provide immediate access to their medication safety solutions. This allows nurses to access relevant clinical information quickly and/or drill down to more comprehensive information, thereby providing exactly the right amount of information as needed. Infobuttons also simplify access to WakeMed’s drug compatibility and stability resource, integrating data on 600 drugs and more than 50,000 compatibility results into nurses’ workflow.

- Patient education information in English and Spanish about all aspects of patient care and health. Materials address patient condition, treatment, laboratory tests, follow-up care, psychosocial issues, and continuing health.

Most of these systems had been in place, but the new portal would make them accessible. It would meet nursing’s need for quick, to-the-point data that is accurate and up to date, even if printed for use at the point of care. In April 2006, WakeMed implemented the first release of the portal, which comprised the infobutton-enabled infusion guidelines. In November 2006, WakeMed rolled out an improved version, with an easier-to-navigate, easier-to-read tabbed format. Based on nursing feedback, tabs were built that would bring the user directly into patient education, drug-drug interaction, and IV compatibility decision support tools. Expanding the portal led to wider use of MED Smart throughout the organization.

Better Information for Better Patient Care

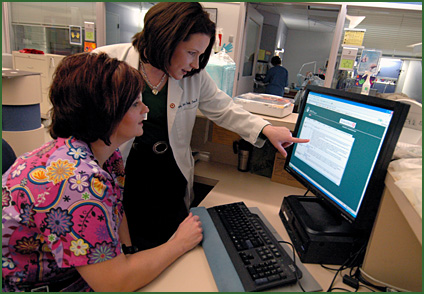

An intuitive system, MED Smart required no formal training and was implemented using “super users” in a train-the-trainer approach. It did not take long for nurses to understand, embrace, and start using the unique system. Their response has been overwhelmingly positive.

A January survey of MED Smart users found:

- 86.7% of nurses use the online resource and integrate it into workflow.

- 79.5% are using the system more than they were three months before.

- 95.6% believe MED Smart improved productivity, efficiency, and time management as compared to previous solutions

- 93.3% have spent less time calling pharmacy for answers.

More importantly, however, MED Smart has helped create an evidence-based practice environment — 62.8% report seeking evidence-based references more often; 95.6% find answers to their questions most of the time; 47.7% say those answers have influenced their decisions or altered the course of therapy; and 88.6% are more confident about their clinical decisions.

MED Smart gives WakeMed nurses ready access to updated information how they need it and as they need it. As a result, they have been more than willing to set aside paper-based notebooks and handwritten notes.

Going forward

Future plans for MED Smart include:

- Rolling out MED Smart to other care settings, including physician offices, skilled nursing facilities, and home care.

- Incorporating pediatric IV guidelines.

- Integrating infobuttons into other clinical information systems across the enterprise.

When it comes to quality care, WakeMed’s goal is to be a leader. MED Smart is one innovative way to achieve that goal.

Angela Smith is clinical pharmacy supervisor at WakeMed Health & Hospitals in Raleigh, North Carolina. She is a graduate of the Doctor of Pharmacy program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Smith’s practice focus is critical care and trauma. She may be contacted at absmith@wakemed.org.

|

References

Gupta A., & Waldhauser L. K. (1997). Adverse drug reactions from birth to early childhood. Pediatric clinics of North America, 44(11), 79-92.

Hicks, R.W, & Becker, S.C. (2006). An overview of intravenous-related medication administration errors as reported to MEDMARX®, a national medication error-reporting program. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 9(1), 20-27.

Levine S.R., Cohen M.R., Blanchard N.R., et al. (2001). Guidelines for preventing medication errors in pediatrics. Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 6(5), 426 Ç442.

Maviglia S., Yoon C., Bates D., & Kuperman G. (2006). KnowledgeLink: Impact of context sensitive information retrieval on clinicians’ information needs. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13(1):67-73.

Phillips J., Beam S., Brinker A., et al. (2001). Retrospective analysis of mortalities associated with medication errors. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 58(19), 1835-1841.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (n.d.). Surviving a heart attack. Retrieved January 25, 2007 from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/actintime/saha/saha.htm

Thomas, M.R., Holquist, C., & Phillips, J. (2001). Med error reports to FDA show a mixed bag. Drug Topics, 145(23). Retrieved January 26, 2007 from http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/MedErrors/mixed.pdf

Tourville, J. (2003). Automation and error reduction: How technology is helping Children’s Medical Center of Dallas reach zero-error tolerance. U.S. Pharmacist, 28(06), 80-86.

Trissels.info. Retrieved January 26, 2007 from http://www.trissels.info/electronicproducts.htm