Mitigate Risk and Drive Organizational Change with Just Culture

May / June 2012

Mitigate Risk and Drive Organizational Change with Just Culture

By Barbara Lightizer, MS, MA, CPHRM, and Bert Thurlo-Walsh, RN, MM, CPHQ

Reporting adverse events is part of the culture at Newton-Wellesley Hospital (NWH). NWH implemented an electronic incident reporting system in 2006. Reporting safety events in an electronic system gives the organization the real-time information it needs to mitigate risks. It also helps the hospital’s risk management staff focus on patient safety improvement strategies that help drive organizational change.

NWH’s risk managers use reports generated by its electronic system to determine if events require immediate follow-up or if a root cause analysis is warranted. In addition, events that meet regulatory reporting requirements for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s Serious Reportable Events and Food & Drug Administration’s Safe Medical Device Act are further investigated to ensure timely reporting. As well, department managers are alerted to submitted reports through an email alert for individual review. A severity score is assigned to each event to measure the actual or potential injury/harm resulting from the event. The options on the scale are:

0 – Near miss/potential harm

1 – No harm/damage

2 – Temporary or minor

3 – Permanent or major

4 – Death

Events with a severity rating of 3 or 4 trigger alerts to the Health Care Quality (HCQ) team and the director/managers of the unit or area.

Processes

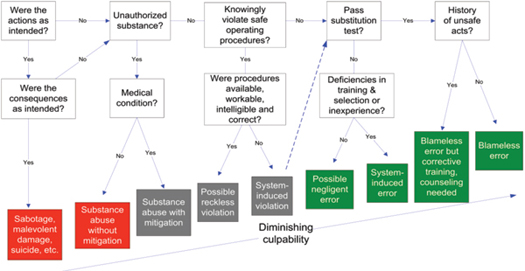

Like every healthcare organization, NWH strives to improve its safety culture. In 2010, NWH’s Health Care Quality team started applying James Reason’s Culpability Model algorithm (Figure 1) to its safety events. James Reason, a professor emeritus of psychology at England’s University of Manchester, famously developed the Swiss Cheese Model and Culpability Model (or Decision Tree Model), which are both widely used in quality, patient safety, and risk management. The Culpability Model, better known as the “Just Culture” model, is used to determine culpability based on human factors versus system factors, which is the model of Just Culture. It also helps determine whether an event occurred because of individual accountability or system failure, which is also known as a “blameless error.”

Figure 1: Decision Tree for Determining Culpability of Unsafe Acts (Adapted from James Reason, 1997).

Reason’s algorithm uses a series of questions to explore why the event occurred and to determine culpability. The first set of questions is designed to determine if the resulting harm was deliberate. If the actions and consequences were executed as intended, the error would be deliberate and possibly criminal. If the answers to the questions determine that the actions were not executed as intended, the next test of culpability is incapacity. For example, was the staff member involved in the event using drugs or alcohol? If so, were there any mitigating factors (i.e., the staff member has a medical condition for which the drugs were prescribed)?

The next test involves foresight, and these questions relate to situations when an individual knowingly violates procedures (i.e., taking shortcuts). The questions that need to be asked here refer to adequate staffing, training procedures, and the availability of relevant policies. The last of the four tests is the substitution test: could a different person have made the same error under similar circumstances? If the answer to the substitution test is yes, than the error is blameless.

As you can see in Figure 1, moving to the right in the diagram, the error is more “blameless,” and the likelihood that system-related issues are involved increases.

Solutions

Newton-Wellesley Hospital’s HCQ leadership team comprises members of the healthcare quality department including the director, patient safety advisor, staff risk manager, risk manager, manager of quality and patient safety, and administrative assistant. Together, they review all of the hospital’s incident reports, regardless of severity rating, to look for trends, discuss priorities, and determine follow-up actions. The team also reviews General Incident and Specific Incident Type categories for accuracy. Depending on the severity of the event and the follow-up completed to date, the team triages the event. If additional follow-up is required, it is assigned to a member of the HCQ leadership team. The team also decides if events should be triaged to specific committees for further review. If trending is noted, they determine which department is responsible for the follow-up and process improvement. This approach is similar to many other hospitals. Where NWH sets itself apart is what it does next.

After the HCQ leadership team finishes its review, it sends a report of selected incidents from the previous week to the Service Operations Committee (SOC). Their weekly meeting is chaired by the president of Newton-Wellesley Hospital and is made up of approximately 40 people, including the executive management team, department chairs and service chiefs, directors and managers of all service lines. The SOC’s original purpose was to review positive and negative comments submitted by patients on satisfaction surveys. Now, its added mandate is to review select safety reports (usually 2 to 4 reports per meeting) and identify opportunities for multi-department shared learning.

For each safety event discussed at the SOC, the clinical leader of the corresponding department presents the event to the committee, after he or she is prepped by the risk management team., After that, the discussion takes on a life of its own; the focus shifts from the individual event to how it affects the organization as a whole. This level of executive input on reviewing safety events on an ongoing basis is unusual at acute care facilities. Moreover, the cross-departmental makeup of the SOC has resulted in invaluable discussions.

In addition, the structure of the SOC meetings ensures that they’re always productive and well attended. Since the meeting is chaired by the president of the hospital and comprises both clinical and non-clinical leadership, patient safety is clearly a priority for everyone at NWH. As well, since the meetings are held weekly and are only an hour long, decisions are made quickly, and the discussion is timely.

At the SOC meetings, the emphasis is on reviewing adverse events in a non-punitive way; the goal is to make the discussion a positive experience for those involved. For success, a committee such as this requires a high level of engagement. At NWH, everyone sits together in one room and collaborates on the issues to identify opportunities, not place blame. This non-judgmental atmosphere means that the SOC often uncovers implications and solutions that the HCQ might not have identified otherwise.

Outcomes

The SOC has helped reinforce the message of a Just Culture for effective reporting at NWH. Any organizational changes or process improvements that have come about as a direct result of safety event reviews are also presented to the Service Operations Committee. For example, the rich discussion of an event at the SOC last fall (see Case Study for a detailed account of the incident) lead to several corrective actions being identified and implemented.

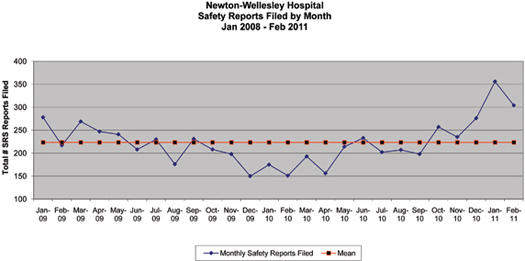

The motivation for working to establish a Just Culture was the desire to have all NWH employees treated consistently and fairly between departments. The Just Culture model helps the organization look at events as they exist in a system, not in isolation. The HCQ team was actually pleased to see an increase in the number of events (Figure 2: Safety Reports Filed by Month) because it means that people feel comfortable reporting.

Figure 2: Safety Reports Filed by Month

As well, now that the SOC has made Just Culture a priority, the quality of the reports has improved (i.e., more descriptive details). In response, the HCQ team now periodically sends emails to submitters to thank them for submitting the report. They don’t do it for every report—just for the ones that require a personal touch—but the response from staff has been incredible.

Conclusions

While Newton-Wellesley Hospital had a strong, entrenched safety-event reporting culture, emphasizing the James Reason Culpability Model, or Just Culture model, improved patient safety at NWH even more. The introduction of the Service Operations Committee, a multi-department committee chaired by the hospital’s president, further established a non-punitive culture of safety that encouraged reporting and shared learning. Reporting of safety events has increased, but the quality of submitted reports has also increased proportionately.

Barbara Lightizer is manager of risk management, patient relations, and interpreter services at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts. She has more than 20 years of experience in risk management, and holds master’s degrees in counseling and healthcare administration. She is a distinguished fellow of ASHRM and a board member and past president of the Massachusetts Society for Healthcare Risk Management. She has also volunteered as board member of ASHRM and the AHA’s Certification Center, and as the chair of the AHA CPHRM Program Committee. Lightizer may be contacted at blightizer@partners.org.

Bert Thurlo-Walsh is director of healthcare quality at Newton-Wellesley Hospital. He is responsible for the management and oversight of the quality improvement, patient safety, peer review, pay-for-performance initiatives, care coordination, infection control, risk management, patient relations, and interpreter services at NWH. He has more than 25 years of experience in healthcare, with nearly 10 years in quality and patient safety. Thurlo-Walsh has two bachelor’s degrees, one in natural science and mathematics, and the other in nursing. He is a member of NAHQ, MAHQ, AONE, AAMN and ONL MA-RI and may be contacted at bthurlo@partners.org.

About Newton-Wellesley

HospitalNewton-Wellesley Hospital (NWH) is a 289-bed community teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard and Tufts Medical Schools. Located 12 miles west of Boston, Massachusetts, the hospital offers a full range of comprehensive medical, surgical, and specialty programs, and services including intensive care, obstetrics, pediatrics, psychiatric services, and urgent care. NWH is a member of the Partners HealthCare System, a not-for-profit health care system founded by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1994.

Technology Overview

Newton-Wellesley Hospital uses risk management software from RL Solutions for electronic incident reporting, which gives healthcare organizations the adverse event data they need to improve patient safety and quickly identify areas of improvement. RL Solutions’ incident management reporting system, RL6:Risk, has also earned the exclusive endorsement of the American Hospital Association.

|

Timeline Sunday, September 12, 2010: Event appeared in the weekly SRS Incident Summary Report, the report of all events of the previous week. Monday, September 13, 2010: Event appeared in the Daily Risk Review, the report of all events of the previous day (in this case, it includes the weekend). Tuesday, September 13, 2010: Event discussed at weekly Healthcare Quality Leadership Team review of safety reports. Decision made to bring to Service Operations Committee (SOC) for shared learning. Tuesday, September 21, 2010: Event reviewed at the SOC to share awareness to identify and mitigate other potentially similar risk issues which could exist elsewhere. Their conclusion was that it was blameless error because the employee did not knowingly violate safe practices and the employee passed the substitution test. October 2010: A new injector is purchased for the emergency department’s CT so that both locations now have identical set-ups, reducing the possibility of the error reoccurring. |