ISMP: Short of Everything Except Errors: Harm Associated with Drug Shortages

May / June 2012

![]()

ISMP

Short of Everything Except Errors: Harm Associated with Drug Shortages

In the November 3, 2011, ISMP newsletter, we asked hospital pharmacy staff to let us know if the drug shortage problem in the United States has continued to result in harmful outcomes for hospitalized patients. At that time, an Associated Press article had just reported 15 deaths in the prior 15 months that were linked directly to drug shortages (Johnson, 2011). (Thirteen of these deaths had also been reported to ISMP.) In response to our request for information, nearly 100 practitioners took our short survey and strengthened our belief that the ongoing drug shortage crisis is extracting a significant toll on patient safety.

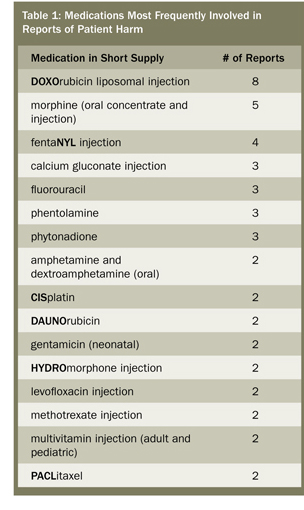

Survey respondents provided a bleak picture of certain and suspected patient harm that has resulted during the past year (March 2011 to March 2012) due to crucial drug shortages. The medications most commonly involved in the reported adverse events include: chemotherapy (27%), particularly DOXOrubicin; opioid analgesics (17%), mostly fentaNYL and morphine; electrolytes (7%); antibiotics (5%); phentolamine (4%); and phytonadione (4%). See Table 1 for a list of medications involved in more than one reported adverse outcome.

Survey respondents provided a bleak picture of certain and suspected patient harm that has resulted during the past year (March 2011 to March 2012) due to crucial drug shortages. The medications most commonly involved in the reported adverse events include: chemotherapy (27%), particularly DOXOrubicin; opioid analgesics (17%), mostly fentaNYL and morphine; electrolytes (7%); antibiotics (5%); phentolamine (4%); and phytonadione (4%). See Table 1 for a list of medications involved in more than one reported adverse outcome.

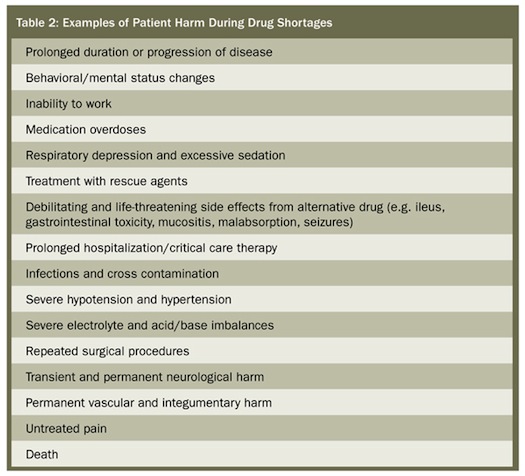

The types of harm reported by respondents included prolonged duration or progression of a disease, transient and permanent injuries, and death (n=4). Table 2 provides examples of the types of harm reported; in many cases, patients suffered more than one type of harm from the drug shortage. Problems associated with a drug shortage that resulted in harm fell primarily into four categories:

- Alternative medication provided, but it was not the drug of choice, which led to inadequate treatment (35%)

- An error with an alternative drug or form/strength of a drug used as a substitution for the drug in short supply (27%)

- An omission of vital medication leading to non-treatment of the patient (27%)

- An error when a hospital pharmacy attempted to compound a product or drug strength no longer available (6%).

Events Involving Adults and Older Adults

The majority of harmful events reported by respondents affected adults between the ages of 19 and 64 years (57%) and 65 to 80 years (20%). A number of examples follow.

- Unfamiliarity with BREVITAL SODIUM (methohexital), used as a substitute for propofol, resulted in a serious dilution error during reconstitution of the powder. The patient ultimately received a massive overdose of the drug and died despite resuscitation efforts.

- Prior to a midazolam shortage, the anesthesia department had been supplied with 5 mg/5 mL vials of midazolam. Once the medication was withdrawn into a syringe, some anesthesiologists had developed an unsafe habit of determining whether the syringe was new or used by the remaining volume in the syringe; anything less than 5 mL signaled a “used” syringe. During the shortage, 2 mg/2 mL vials of midazolam were sometimes dispensed in place of the 5 mg/5 mL vials (same concentration). With the 2 mL vials, syringe volumes of less than 5 mL could no longer signal a “used” syringe since a new syringe could contain just 2 mL. Fluctuating volumes of midazolam vials contributed to using the same syringe to administer midazolam to two patients. A 5 mg/5 mL vial of midazolam had been withdrawn into a syringe and used to administer 3 mg (3 mL) of the medication. The remaining 2 mg (2 mL) in the syringe was mistakenly thought to be a new syringe of midazolam from a 2 mg/mL vial, which was administered to another patient.

- During a fentaNYL shortage, a patient who was unable to take morphine or HYDROmorphone was prescribed meperidine. She experienced extreme nausea and vomiting unrelieved by ondansetron.

- During a morphine shortage, a physician prescribed, a pharmacist approved, and a nurse administered HYDROmorphone 2 mg IV to an opioid-naïve patient (approximately equivalent to 14 mg of morphine). The patient required naloxone and monitoring in a critical care unit.

- During a shortage of calcium gluconate, calcium chloride was administered IV to treat an electrolyte imbalance. The higher osmolarity of the undiluted calcium chloride solution caused permanent vascular and integumentary harm after it infiltrated into the surrounding tissue.

- A cancer patient had progression of her disease, possibly hastening her death, because she could not complete treatment with DOXOrubicin due to a shortage. It was too late to switch to another protocol.

- During a shortage of multivitamins, a patient receiving parenteral nutrition without multivitamins was given an oral multivitamin supplement. The patient developed signs of Wernicke encephalopathy (confusion, slurred speech, loss of coordination, unsteady gait, blurred vision, fatigue and sleepiness), at which time it was discovered that the oral multivitamin did not contain thiamine.

- Premixed solutions of bupivacaine 0.5% with EPINEPHrine 1:200,000 were not available. Pharmacy mixed a small batch of solutions for anesthesia but added too much EPINEPHrine during admixture. Two patients developed hypertension, ventricular fibrillation, and pulmonary edema, requiring extended hospitalization in a critical care unit. One patient required mechanical ventilation.

Events Involving Infants and Children

Twenty percent of the events reported in the survey involved pediatric patients between the ages of 0 to 1 year (12%) and 2 to 10 years (8%). Examples within these age groups are provided below.

- During a cysteine shortage, inability to add this product to amino acids led to iatrogenic fractures in two infants, an injury not seen previously in the facility despite years of treating infants on long-term parenteral nutrition. (Cysteine enhances the solubility of calcium and phosphates.)

- Using TRAVASOL (amino acid injection) during a shortage of TROPHAMINE (amino acid injection preferred for children) in a low-birth-weight neonate’s parenteral nutrition solution led to precipitation of calcium and phosphate, which blocked the child’s Broviac catheter, requiring surgical replacement.

- Ammonium chloride was used during a shortage of arginine to treat hypochloremic alkalosis. Pharmacy staff failed to dilute the ammonium chloride prior to dispensing it (arginine doesn’t require dilution). The infant experienced seizures during the infusion but recovered.

- Stem cell transplant was delayed for a second time in a young child with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) because there was no busulfan to be found in the state or through the wholesaler. Eventually, a nurse drove 3 hours to another state after completing a full evening shift to borrow the needed doses. Staff are unable to determine if the delays affected the success of the treatment.

- During a shortage of DAUNOrubicin, children received induction treatment for ALL or AML (acute myeloid leukemia) with DOXOrubicin (typically not used in children) and experienced severe mucositis and gastrointestinal bleeding.

|

Readers will notice special typographic treatment of drug names in this column. Capitalization and bold type are used to identify brand or generic drugs as well as confusing look-alike/sound-alike drug names. This follows a standardized process ISMP applies to the way drug names appear in print in its publications. The first time a brand drug name is mentioned, it is in bold, uppercase letters (e.g., PLAVIX). Subsequent listings of the brand drug name are shown with only the first letter of the name being capitalized (e.g., Plavix). All generic drug names are in lowercase letters (unless they start a sentence). The only other exception to both brand and generic drug names are if they are on FDA’s or ISMP’s list of look-alike, sound-alike drugs names. Some of these have been selected to incorporate mixed case lettering, also referred to as “tall man” lettering. We use bold, uppercase letters within the name to differentiate them (e.g., DOPamine, DOBUTamine, HumaLOG, HumuLIN). There are a few brand drug names that use tall-man letters which may or may not incorporate the tall man letter scheme in the initial letter (e.g., AVINza, CeleBREX). Tall man is a concept ISMP developed in the 1990s to help make the unique letter characters in look-alike names dissimilar. ISMP periodically revises the list of “confused” drug names (http://www.ismp.org/tools/confuseddrugnames.pdf) with input from the field. Thanks to Lisa Shiroff, administrative assistant, and Michael Cohen, president, of ISMP for their help with this explanation. |

We sincerely thank our survey respondents for allowing us a glimpse of the enormous toll that drug shortages are taking on patients and their healthcare providers who are faced with the problem on a daily basis. With only about a hundred practitioners responding to our survey, the adverse events related to drug shortages reported to ISMP likely represent just a fraction of the actual harm from drug shortages occurring today. Recently, the results of another survey conducted by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) revealed that seven anesthesiologists had reported shortages that led to death in their patients (http://abcnews.go.com/Health/abc-news-exclusive-anesthesia-drug-shortages/story?id=16123792). The seven anesthesiologists responded to the question “How has a drug shortage impacted your patients?” by checking the option, “Has resulted in death of patient,” according to ABCNews.com. One of the four deaths reported to ISMP involved a general anesthetic agent used as an alternative medication during a propofol shortage. A similar ASA survey in 2011 included reports of two patient deaths.

ISMP will continue its efforts, in cooperation with the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and many other partner organizations (e.g., American Hospital Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Anesthesiologists) to articulate the scope of this problem, and to develop a plan to reduce the occurrence of drug shortages and better manage them when they occur. We will keep readers well-informed of progress to this end. Meanwhile, we offer some stop-gap guidance for managing drug shortages on a local level within healthcare organizations at: www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20101007.asp.

This column was prepared by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), an independent, nonprofit charitable organization dedicated entirely to medication error prevention and safe medication use. Any reports described in this column were received through the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported online at www.ismp.org or by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE (800-324-5723). ISMP is a federally certified patient safety organization (PSO), providing legal protection and confidentiality for patient safety data and error reports it receives. Visit www.ismp.org for more information on ISMP’s medication safety newsletters and other risk reduction tools.

This article previously appeared in the ISMP Medication Safety Alert: Acute Care, April 19, 2012.