From Blame to Fair and Just Culture: A Hospital in the Middle East Shifts Its Paradigm

July/August 2013

![]()

From Blame to Fair and Just Culture:

A Hospital in the Middle East Shifts Its Paradigm

Tawam Hospital, United Arab Emirates

The concept of a “culture of safety” emerged from high reliability organizations (HROs) such as in the aviation and nuclear power industries. The objective of HROs is to consistently minimize adverse events despite carrying out inherently intricate and hazardous work. These organizations maintain a commitment to safety at all levels, from frontline providers to managers and executives. Improving the culture of safety within healthcare is long overdue and is now becoming essential to preventing and reducing errors, thereby improving overall healthcare quality (AHRQ, n.d.).

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) groundbreaking report, To Err Is Human (2000), found that as many as 98,000 people die each year from medical errors in hospitals in the United States alone, making medical errors a more common cause of death than motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS. The report estimated that these errors cost the United States nearly $38 billion each year (IOM, 2000).

Now, more than 10 years after the IOM report, medical errors are still a widespread problem in the United States. It has been estimated that more than 1.5 million people have been sickened, injured, or killed by medication errors each year since the report was issued and an estimated 1.7 million persons have battled illnesses due to hospital acquired infections, with tens of thousands dying (Clark, 2009).

The concept of patient safety is an emerging philosophy for healthcare organizations in the Middle East. Coupled with this emerging philosophy is a lack of a cohesive research agenda focused on capturing patient harm due to medical errors. In affiliation with Johns Hopkins Medicine, Tawam Hospital—one of the largest hospitals in the United Arab Emirates—has taken a proactive stance for patient safety and has helped to spearhead the patient safety movement in the region.

Tawam Hospital faced many of the same barriers to patient safety present in hospitals elsewhere such as communication hierarchies among providers and lack of a supportive environment in which to report errors without fear of repercussions (Stein, 1967). A culture unaccustomed to acknowledging medical errors and a tendency for poor communication and teamwork often lead to adverse events (IOM, 2000). Tawam Hospital also has a unique set of challenges in that it employs staff from more than 60 nations, making cross-cultural communication a strong variable in patient safety efforts.

Many of these caregivers have traditionally felt an added reluctance to admit mistakes because doing so might jeopardize their jobs. The gap between timid nurses who were unable to speak up and assertive and authoritative physicians has been a major communication barrier.

Tawam Hospital’s executive leadership realized that the best way to enhance patient safety is to build a culture of safety at the hospital, so in January 2008 they launched the Johns Hopkins Hospital Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP). Early in the safety movement at Tawam, the leadership created a patient safety department specifically to roll out staff education and program standards. The department consists of four patient safety officers and a medication safety officer. The affiliation of Tawam Hospital with Johns Hopkins Medicine, which began in 2006, provided access to experts for training in the science of patient safety and human factors engineering.

In 2008, the intensive care unit (ICU), neonatal intensive care unit (NNU), and pediatric oncology unit were selected to be CUSP pilot units to assess the acceptance of the new safety culture philosophy. The units were selected in part due to their high-risk, high-volume nature and their use of closed medical staffs. Senior executive leaders of the hospital were assigned to each of the pilot units, where they formed multidisciplinary teams in accordance with CUSP’s true meaning as a partnership-driven program (Pronovost, et al., 2004).

Culture Assessment Survey

Safety culture is generally measured by surveys of providers at all levels. Available validated surveys include the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPS) from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality and the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) from Pascal Metrics. These surveys ask providers to rate the safety culture in their units and in the organization as a whole, specifically with regard to these key features:

- Acknowledgment of the high-risk nature of an organization’s activities and the determination to achieve consistently safe operations.

- A blame-free environment where individuals are able to report errors or near misses without fear of reprimand or punishment.

- Encouragement of collaboration across ranks and disciplines to seek solutions to patient safety problems.

- Organizational commitment of resources to address safety concerns (AHRQ, n.d.).

In the Middle East, studies on safety culture assessment have been conducted in Qatar and in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Al-Ishaq (2008) assessed nurses’ perceptions of safety culture in one Qatar health system, and Al-Ahmadi (2010) has reported safety assessments from healthcare systems in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Both studies reported using the HSOPS instrument. Neither study discussed the use of a structured approach, such as CUSP, to establish an organizational culture of safety prior to or following the staff assessment.

Tawam Hospital adopted a scientific approach to CUSP implementation and conducted pre-test measurement of staff perception of safety culture using the SAQ instrument prior to CUSP implementation.

The SAQ is a survey instrument used in more than 500 hospitals in the United States, United Kingdom, and New Zealand, and has been validated for use in critical care, operating rooms, pharmacy, ambulatory clinics, labor and delivery, and general inpatient settings (Sexton et al., 2006). The SAQ instrument measures culture of safety along seven dimensions: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, stress recognition, working conditions, perceptions of hospital management, and perceptions of unit management (Sexton et al., 2006).

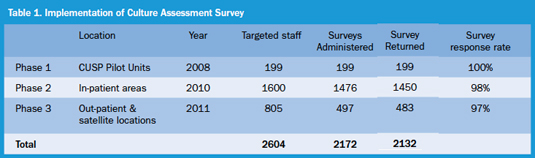

Tawam Hospital partnered with Pascal Metrics to implement the SAQ. The paper-based SAQ was administered to all Tawam Hospital staff in three phases: 2008 (pre-implementation), 2010, and 2011. The SAQ was administered under standardized conditions to ensure staff representation and uniformity across the organization. The results of staff participation during the three phases are illustrated in Table 1. Eighty-two percent of staff in patient care areas participated in the SAQ survey, with an overall response rate of 81% in the three phases combined.

SAQ Results

The survey response is a Likert-like scale with categorical responses: Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, and Strongly Agree. The responses were coded by number and percent for measurement, ranging from 1(0%) for Strongly Disagree, through 5 (100%) for Strongly Agree. The survey results have been graded against percentage positive responses. This is the percent of people who, on an average across items, marked a 4 (Agree) and above, positive responses. That is, it is the percent of people who have a scale score of 4.0 (or 75% on the 0 to 100 scale). Therefore, a unit’s response that is less than a 60% mark—not positive—was graded in the danger zone, and anything above the 80% mark—positive—was graded in the goal zone.

Within the SAQ, the domains of Teamwork and Safety Climate are considered to be the two primary dependent variables with the most significance relationships in preventing patient harm. Secondary dependent variables are defined as morale, stress recognition, working conditions, perceptions of hospital management, and perceptions of unit management (Timmel et al., 2010).

Comparison of Pilot CUSP Units 2008 and 2010

A comparison of the SAQs pre- and post-CUSP implementation shows that the ICU had sustained its scores on the job satisfaction domain and has shown an increase in the other domains—a trend towards improved unit culture. Six out of the seven domains, however, are still below the 60% percentile mark, indicating a danger zone.

The scores of the Pediatric Oncology Unit significantly dropped in six domains except for the stress recognition domain. All scores remained below the 60% percentile mark, indicating danger zone and potentially a declining unit culture.

The NNU sustained their job satisfaction scores, improved teamwork scores, and dropped on the safety climate scores. Four domains had low scores indicating a danger zone and an overall mixed result in unit culture.

Results of 2010 and 2011

In the 2010 and 2011 SAQ surveys, the overall hospital score on all the domains were in the danger zone—less than 60%—and 20 clinical locations in 2010 and 7 clinical locations in 2011 had scores of less than 60% in the primary dependent variables.

Amongst the secondary dependant variables, perception of hospital management was the lowest scoring domain in all three phases of the survey. This could be attributed to staff being more familiar with their unit management addressing their concerns than the hospital management.

There were two additional items in the SAQs of significance for the senior leadership:

1. Safety: In 2010 and 2011, a total of 17 units scored less than 60% for the question, “I would feel safe being treated here as a patient.” Post-hoc analysis of this area using qualitative inquiry found that staff interpreted this question to mean their own personal safety rather than an assessment of “safe” medical care in a particular unit or service line.

2. Job satisfaction: 20 units scored less than 60% in the content domain related to job satisfaction indicating a unit culture where the implementation of a patient safety program might not achieve intended outcomes unless more pressing issues are addressed.

The senior leadership was keen to address these themes to enhance the culture of safety.

Results Debriefing and Action Plan

The SAQ results were disseminated to each department in the presence of a senior hospital executive. Every department was then asked to set up an action plan using the SAQ de-briefer tool. The de-briefer tool contains the least positive and most positive scores. The unit staff selected one or two items from the least positive scores, identified specific areas of concern, and developed action plans for improvement. The hospital administrators, playing a facilitator role in conjunction with the patient safety officer, helped the departments to develop actionable plans.

Challenges Faced with the SAQs

Since English is not the first language for most staff at Tawam Hospital, it was felt that the questions did not translate as expected due to syntax issues, sentence structure, and language rules. For example, the question, “I would feel safe being treated here as a patient,” as previously noted, was misinterpreted by many staff as their own physical safety in the unit. This was due to instances of aggressive behaviors in the unit. For other staff, it was not clear if the phrase meant being treated as a patient in the unit in which they worked or in the hospital. Likewise, staff misinterpreted questions such as, “Problem personnel are dealt with constructively by our management,” as a statement about personal problems.

Additionally, some staff and unit leadership took results personally if the department scores were low, and overall they described the unit as “failed” when scores were recorded in the danger zone.

Executive WalkRounds™

The CUSP monthly meetings and executive WalkRounds provided an opportunity for the executive leaders to address issues raised in the two-question survey and SAQ results. The purpose behind the meetings and WalkRounds is to integrate safety into the culture of a unit/clinical area (Thomas et al., 2005).

During these leadership rounds, executives focused on some of the questions that scored low in the SAQs for that particular unit. For example, executives sought to explore the prevalence of teamwork in the unit, how physicians and nurses worked together as a well-coordinated team, and whether nursing input was well-received in the work setting.

Challenges

Tawam Hospital leaders quickly found that not every aspect of Johns Hopkins CUSP methodology translated word-for-word at the hospital. Leaders asked frontline staff the two-unit safety questions and found that staff members often were uncertain how to respond, no matter how many ways the questions were phrased. Instead of bringing up dangers, staff typically talked about the protocols they followed to prevent harm. Leaders have now modified their walk rounds questions and ask pointed questions. For instance, Have you had any problems with pharmacy recently on medications prepared for the ICU? How is your communication with the physicians? Reformatting the questions has shown to improve the tangible information that is actionable.

Learning from Defects

In 2008, within a month after the roll out of CUSP in pediatric oncology, two medication errors were reported. Upon full investigation, it was determined that a nurse had failed to perform the final check of Five Rights of medication administration and inadvertently administered chemotherapy to the wrong patient. The second error, minor in nature, resulted from administration of an expired routine vaccination. Again, a nurse failed to perform the Five Rights safety checks. Neither case resulted in patient harm. In both the cases, the errors happened to highly experienced charge nurses on the unit.

Since CUSP and the philosophy of patient safety were in progress with the pediatric oncology team, the staff members were motivated to be open and report incidents. A CUSP-driven investigation of both incidents, examining processes and not just people, substantiated the organization’s practice of a “fair and just” culture and instilled confidence in the staff that this cultural shift was indeed a reality.

The two charge nurses not only shared their personal experiences with the pediatric oncology staff members, but have gone on as advocates of patient safety by sharing their experiences with nurses in the other CUSP units and throughout the organization. This incident served as a perfect example to all staff in the three CUSP units: there is no substitute for constant learning from defects, and culture change is both evolutionary and revolutionary.

Lessons learned from the pediatric oncology errors pushed leadership to establish Safety Analysis Teams in the CUSP units. The primary aim was to encourage and improve staff awareness of incident reporting and learning from defects, proactively identify and implement risk reduction strategies, and finally to enhance the culture of safety.

These team members meet on a monthly basis prior to CUSP meetings to review incident reports submitted to Patient Safety Net (PSN®), the event reporting system for the University HealthSystem Consortium. Information from focused incident analyses has helped the team identify one or two defects for learning, planning and implementing systems changes wherever required to reduce the probability of the incident recurring (Pronovost et al., 2006).

Conclusion

Efforts are now underway in the UAE, Qatar, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to collect data on medical errors in a systematic process. The integration of such information across the region will benefit all organizations as well as health policy at the government level.

What began as a pilot project in 2008 at Tawam has now expanded to include seven additional units. Tawam Hospital now has 10 actively functioning CUSP units representing critical care, pediatrics, and general medical surgical services, and recently, ob/gyn services. Today, the pilot units have completed 5 years of CUSP implementation and six out of the seven new CUSP units have completed 1 year of implementation. The culture of safety is a never-ending journey.

Building trust amongst care providers in CUSP units is a key imperative. Although some of the Tawam units have been in CUSP for many years, we still continue to face challenges to keep staff actively involved in the program. To empower staff and inculcate leadership qualities, CUSP meetings are being chaired by frontline staff members. The CUSP executive remains present but serves in a supportive role for team mentorship. It is estimated that it may take as long as 5 years to develop a culture of safety that is felt throughout an organization (Ginsberg, Norton, Casebeer, & Lewis, 2005). Tawam Hospital’s leadership supports the journey to build a culture of safety; a journey that is built on patience, perseverance, commitment, and engagement.

Krishnan Sankaranarayanan is the senior safety officer at Tawam Hospital. He holds a master of science degree in patient safety leadership from the University of Illinois-Chicago and a master of business administration degree from Annamalai University He is a Certified Professional in Healthcare Quality (CPHQ) and a founding member of the Patient Safety Team at Tawam Hospital. Sankaranarayanan may be contacted at ksankara@tawamhospital.ae.

Steven A. Matarelli works for Johns Hopkins Medicine International and serves as the chief operating officer for Tawam Hospital. Matarelli holds a dual master’s degree in medical surgical nursing and nursing administration and a PhD in public health. Matarelli is a founding Patient Safety Team executive at Tawam Hospital.

Hasrat Parkar has 25 years of experience in family medicine in the UK and UAE and 8 years as an administrator in primary care. He is the interim chief quality officer at Tawam Hospital.

Mamoon Abu Haltem is a patient safety officer at Tawam Hospital, and a founding member of the Patient Safety Team. He is a registered nurse and holds a master’s degree in environmental health science from United Arab Emirates University. He has completed a certificate program in healthcare risk management from American Institute for Healthcare Quality.

References

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the leadership of Johns Hopkins Medicine Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care, the executive leadership of Tawam Hospital, and the CUSP team members for their efforts in implementing the culture of safety program at Tawam Hospital and finally Pascal Metrics for helping Tawam Hospital to measure safety cultures.