Faster Time to PTCA: Improving Safety, Communication, and Satisfaction

July / August 2005

Faster Time to PTCA

Improving Safety, Communication, and Satisfaction

In June 2003, Stony Brook University Hospital, a 504-bed tertiary care facility on Long Island, New York, performed a review of door-to-PTCA (percutaneous transluminal angioplasty) times, which revealed that acute myocardial infarction (AMI) transfers from other hospitals arrived at the cardiac catheterization lab sooner than those from Stony Brook’s own emergency department. The hospital formed a performance improvement team with representation from all personnel directly involved in AMI patient care (emergency department and cardiac catheterization laboratory). In response to the need for a more direct and simplified system to provide emergent revascularization, a Code H (Heart) Team was established. A new process was implemented where, once an AMI patient is identified, the emergency room immediately calls a Code H by overhead page and team beeper. All needed personnel are notified and are required to respond through a single call. If the required cardiac catheterization lab team members do not respond within 10 minutes, the patient is treated with thrombolysis, thereby meeting the required door-to-needle time.

Two time intervals were monitored to identify opportunities for improvement:

a) The time elapsed, beginning when the patient arrives in the emergency department until the time the patient reaches the cardiac catheterization lab.

b) The time elapsed, beginning when the patient arrives in the cardiac catheterization laboratory until the time when the balloon is utilized.

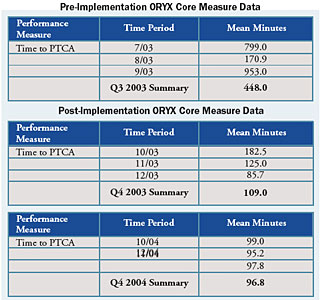

Using FOCUS-PDCA CQI* methodology to improve organizational processes, the Code H Team collected baseline data to identify the performance gap based on the JCAHO ORYX target of 90 minutes. The team developed a flowchart of the process, starting when the patient arrived in the emergency department and ending when the balloon was inflated. Next, the team created a cause-and-effect diagram to identify the factors that contributed to measurable delays.

The Code H Team used the data and CQI tools to formulate an action plan that would impact organizational effectiveness, quality, and patient safety. The Code H process was initiated on October 17, 2003. The process changes were then measured to determine whether outcome and quality of care improved for all emergency department AMIs and fell within the AMI Core Measures of door-to-balloon within 90 minutes or door-to-needle within 30 minutes.

Rationale for Selection

Stony Brook University Hospital’s senior executive leadership identified and communicated key strategic imperatives for the organization, which are linked to performance standards for each service and department. The five key strategic imperatives for Stony Brook University Hospital are:

- Quality and Patient Safety

- Operations Excellence/Electronic Record

- Implementing Strategic Plan — Building Cancer, Heart, Peri-natal, and Surgical Services

- Improving Patient Satisfaction/Customer Satisfaction

- Meeting Financial Targets

To address the strategic imperative relating to quality and patient safety, the organization monitors key clinical indicators, which are incorporated into service-specific dashboards used to track and trend performance relating to processes. Most notably, the organization complies with the ORYX requirements mandated by JCAHO. Stony Brook University Hospital chose to monitor the AMI Core Measure set because of its link to the strategic plan and also because of a desire to select a high-volume, high-risk, Core Measure set related to patient safety, which would provide the organization with meaningful, actionable data to improve performance and enhance patient safety.

Review of the time to PTCA and additional data collected by the cardiac catheterization laboratory revealed opportunities for improvement in turnaround time from door to balloon.

Time to PTCA, if improved, would provide value for a variety of stakeholders:

- Patients. Improved time to PTCA can reduce complications and result in improved clinical outcomes.

- Providers. Changes may result in more effective and efficient processes for managing AMI patients requiring a cardiac catheterization. Improved process changes may enhance the healthcare team’s ability to communicate more effectively, triage and diagnose the patient more rapidly, and provide a workflow that focuses on patients’ needs.

- Organization. The ability of the organization to address the public’s need to ensure a safe, quality-driven experience is enhanced. Furthermore, patients who are satisfied with the care received can serve as a reference for other potential patients.

- Community. Using new EKG technology in local ambulance services allows the physician to call a Code H immediately rather than having to wait until the patient arrives at the hospital. This allows the cardiac catheterization laboratory to respond more promptly, awaiting the patient when he or she arrives in the emergency department and reducing turnaround time.

The Role of Leadership

The associate director of critical care nursing served as the administrative sponsor for the Code H Performance Improvement Team. Associate directors are members of Stony Brook University Hospital’s executive staff. The administrative sponsor attended all of the team meetings and offered administrative and budget support to ensure that the process changes would be accomplished. This administrator was an important champion for coordinating efforts to provide the budgetary support required to institute reward and recognition for staff and physicians when goals were met for door-to-balloon times.

In addition, all teams chartered through the organization’s Clinical Service Groups report activities to the Quality Committee of the Governing Body for discussion and review. Members of the Quality Committee of the Governing Body include the chief executive officer, chief nursing officer, chief operating officer, chief medical officer, associate medical director for quality management, assistant director for regulatory and medical affairs, key physician chairs, and others. The Committee fully supported the team’s activities and noted the progress after process changes were implemented.

Finally, senior executive leadership communicated the team’s progress in a variety of forums including Stony Brook University Hospital’s Continuous Quality Improvement Recognition Ceremony, department head meetings, executive staff meetings and others. Constant reinforcement at key meetings by senior executive leaders promotes the organization’s culture for “Creating a Respectful Environment” (also known as the CARE initiative).

Project Results

When the CQI team first formed, there was uncertainty about whether or not target goals could be met. Communication between departments was not optimal. As a result of meeting together, sharing data, generating flowcharts and cause and effect diagrams, and identifying root causes contributing to process delays in door-to-balloon times, the team became energized and worked together in a collaborative manner. Since staff from varying levels in the organization were asked to serve on the team, and their ideas were realized in process improvements, employee morale and job satisfaction improved. Communication of staff members within and between departments has improved considerably, resulting in better decision-making. Through team meetings, the group developed an innovative partnership by sharing and exchanging ideas with an eye toward improving emergency medical care for our patients. Team members were empowered to develop solutions to problems that were noted on the cause-and-effect diagram.

A more concrete example of changing the employee satisfaction level is the implementation of a reward and recognition program to recognize healthcare team members who contributed, as Code H responders, to meeting door-to-balloon targets. All cardiac catheterization and emergency department employees and physicians receive a pin that states “I Saved a Heart” whenever the 90-minute target is met.

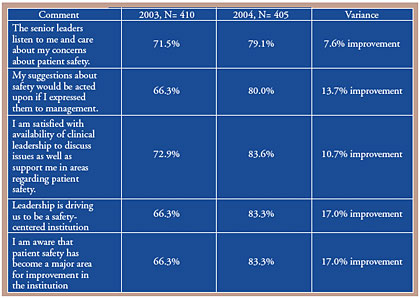

In terms of employee perception, the Code H team, by virtue of reducing the turnaround time from door-to-balloon, understood the impact that was made to improve patient safety and clinical outcomes. A Patient Safety Cultural Survey administered in 2003 and 2004 revealed the data seen in Table 1.

|

These data demonstrate the staff and physicians’ perceptions of the organization’s approach to patient safety. Gains were made in virtually every aspect surveyed. The Code H team, highlighted and recognized in several forums by senior executive leaders and others, demonstrated to all concerned a tangible effort that used ideas generated from team members who were empowered to implement process changes to improve patient care and patient safety. This project reinforces the organization’s true commitment to quality and patient safety, indicated as Stony Brook University Hospital’s key strategic priority.

Beepers/pagers were purchased to facilitate group paging for Code H responders. The group paging mechanism allows all team members to be contacted simultaneously in order to avoid delays and attend to the patient as swiftly as possible. The Code H flow sheet, designed using evidence-based literature, is utilized to ensure consistency in documentation, communication, and care rendered for patients requiring revascularization via the Code H process.

Community Resources

Our team members asked the medical director for Suffolk County to ensure that ambulances are equipped with 12-lead EKGs in order for data to be transmitted from the field, to shorten door-to-balloon turnaround time. A 12-lead EKG records the electrical activity of the heart from twelve locations on the body. Six chest leads measure the electrical activity of the anterior, posterior, and lateral cardiac walls and record cardiac forces on the horizontal plane. The limb leads measure forces on the frontal plane. The 12-lead EKG is considered the key to the evaluation of a heart attack.

Ambulances in the field utilize 12-lead EKG to transmit data to the emergency department from the field. This allows the physician to triage and diagnose more readily and facilitates the process of communicating a Code H in progress to personnel in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The process ensures a systematic, consistent approach to enhancing optimum care for our patients. In addition, the data for these outcomes are reported publicly through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Public Reporting Initiative. The community can review the data and make determinations about the selection of healthcare providers. Stony Brook’s chief medical officer worked closely with community physicians by sharing the goals and outcomes of this initiative.

|

|

With the exception of developing the Code H flowsheet, all project goals were achieved in the timeframe established. The development of the Code H flowsheet required the input of representatives from key stakeholder and “expert” departments such as pharmacy, laboratory, cardiology, and others, to ensure the development of a superior product, which led the team to extend the deadline in order to complete this task.

The initial need for a more direct and simplified system to provide emergent revascularization was addressed by applying the traditional Trauma Code (Code T) concept to Acute MI. The Code H was developed and implemented successfully for AMI patients, specifically piloted for patients entering the emergency department.

The success of the team’s outcomes allowed the team to replicate this process for patients in the medical intensive care unit and coronary care unit who experience AMI symptoms. Similar to the Code H called in the field or in the emergency department, a Code H can be called in those units when the criteria for a Code H are met.

Lessons Learned

The organization has made significant strides on many fronts with respect to this initiative. Through the CQI process, the team learned many lessons:

- Constant reinforcement at key meetings by senior executive leaders promotes the organization’s commitment to a respectful work environment. It also reinforces positive behavior such that creativity, innovation, and risk-taking are welcomed and applauded by leadership in order to meet stretch targets to improve organizational performance, work collaboratively between disciplines and departments, and exceed the needs of patients.

- The Code H team, highlighted and recognized in several forums by senior executive leaders and others, demonstrated to all concerned a tangible effort that used the ideas generated from team members who were empowered to implement process changes to improve patient care and patient safety. It also reinforced the organization’s true commitment to quality and patient safety, indicated as our hospital’s key strategic priority.

- By involving external partners in this initiative, staff were able to build collaborative working relationships with the community and serve a common goal, to improve outcomes for patients.

In terms of relevance to other healthcare organizations, the success of the team’s outcomes allowed the team to replicate this process for patients in the medical intensive care unit and coronary care unit experiencing AMI symptoms. More recently, the department of neurology developed a “Code BAT” protocol, using the same communication processes as the Code H initiative, to provide emergency care for acute stroke patients upon arrival in the emergency department. These activities demonstrate that these processes can be replicated in other settings to improve performance, not only for AMI patients, but for other patient populations as well. The Code H team will continue to monitor processes relating to time to PTCA and continuously improve outcomes for AMI patients.

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their significant contributions to this project:

Mary B. Arenas, RN; Patricia Caillias, RN; Michael Davison, RN; Richard Dickinson, MD; Theresa Leonard, RN; Mary Maliszewski, RN; Eric Niegelberg; Arlene Nolan; Karen Sproul, NP

The authors work at Stony Brook University Hospital in East Setauket, New York. Carol Gomes (cgomes@notes.cc.sunysb.edu) is assistant director for medical and regulatory affairs and director for continuous quality improvement. William Lawson is professor of medicine and director of interventional cardiology. Asa Viccellio is clinical professor and vice chair of emergency medicine. Carolyn Santora is associate director for critical care, trauma, emergency department, and intermediate care room services.

Bibliography

Angeja, B. G., Gibson, M., Chin, R., et al. (2002). Predictors of door-to-balloon delay in primary angioplasty. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2002; 89: , 1156-1161.

Brodie, B. R., Stone, G. W., Morice, M. C., et al. (2001). Importance of time to reperfusion on outcomes with primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction (Results from the Stent Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Trial). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2001; 88,: 1085-1090.

Cannon, C. P., Gibson, C. M., Lambrew, C. T., et al. (2000). Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000; 283:, 2941-2947.

Juliard, J. M., Feldman, L. J., Golmard, J. L., et al. (2003). Relation of mortality of primary angioplasty during acute myocardial infarction to door-to-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) Ttime. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003; 91,: 1401 1405.

Kadir, H. A., Ling, M. L., Wong, P., et al. Improvement report: Reduce door-to-balloon time for primary angioplasty in emergency department patients. Institute for Healthcare Quality (IHI). www.qualityhealthcare.org/IHI/

Shry, E. A., Eckart, R. E., Winslow, J. B., et al. (2003). Effect of monitoring physician performance on door-to-balloon time for primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003; 91,: 867-869

Vakili, B. A., & Brown, D. L. (2003). Relation of total annual coronary angioplasty volume of physicians and hospitals on outcome of primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction (Data from the 1995 Coronary Angioplasty Reporting System of the New York State Department of Health.) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003; 91,: 726-728.