Evidence-Based Review Promotes Evidence-Based Medical Practice

September / October 2006

Evidence-Based Review Promotes Evidence-Based Medical Practice

![]()

Participation in utilization management (UM) activities provides physicians who conduct peer clinical reviews with opportunities for experience and training in applying evidence-based medicine (EBM) principles to clinical practice and healthcare decisions (Davis, et al.,2003; Coomarasamy & Khan, 2004). In this article we describe the strategies employed by an independent review organization (IRO) to encourage EBM determinations and the effectiveness of those strategies. The goal is to facilitate physician reviewer activities and to assess whether reviewers would incorporate EBM principles into their daily practice activities and follow evidence-based care. The success of the program was evaluated through internal data analysis and interpretation, anecdotal reports, and through a survey of active physician reviewers.

The University Health Network defines EBM as the “conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.” EBM has continued to influence the practice of medicine since its emergence in generalized use (von Segesser, 2003; Guyatt, et al., 2004; Guyatt, 1991). In our experience at an Independent Review Organization, the percentage of UM reports requiring literature citations in support of the physician reviewer’s rationale has risen from 10% in 1995 to 90% in 2005. Expansion of EBM’s influence to UM is a logical progression. A number of external pressures have contributed to the development of evidence-based utilization management (EBM-UM), such as client requirements, litigation, governmental regulations, and industry standards (hmosettlements.com; US Dept. of Labor, 2000; URAC, 2003; Saami & Gylling, 2004). Currently, 76% of all states and 55% of our client base require evidence-based review criteria in support of medical determinations (URAC, 2005).

A recent landmark settlement makes specific reference to EBM in broad and encompassing terms in the definition of “medically necessary” in “In Re: Managed Care Litigation”:

For these purposes, “generally accepted standards of medical practice” means standards that use clinical guidelines that are based on credible scientific evidence published in peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community; [i.e., Evidence Based Medicine] (taking into account Physician Specialty Society recommendations, the views of Physicians practicing in the relevant clinical areas, and any other relevant factors) when making medical necessity determinations (hmosettlements.com).

This settlement has a far-reaching impact on the medical management industry. It involved major health insurance carriers, effectively impacting every physician in the United States, and set a standard for definitions to be applied to healthcare benefit determinations. To comply with the goals of the settlement, independent review companies need to include strategies to facilitate physician reviewers’ incorporation of EBM into UM activities.

The requirement to research and cite EBM literature in support of healthcare UM determinations has had significant impact on the ability to complete reviews within the time allowed. Review turnaround times established by statute and regulating agencies are often between 24 and 72 hours (US Dept. of Labor, 2000; URAC, 2003). This environment challenges physician reviewers to compile extensive current research while simultaneously accomplishing all the activities of the review process. These activities include receipt and assessment of case records, discussion with the attending physician to address the review questions and the patient’s clinical situation, formulation of a position based on relevant evidence, and dictation of a cogent report (Bhandari, et al., 2004; Montori & Guyatt, 2001; Straus & Sackett, 1998)).

An IRO operating in this increasingly regulated industry faces many challenges to provide healthcare determinations supported by evidence-based medicine literature while meeting mandated turnaround times. Furthermore, the IRO must consistently deliver quality comprehensive reports with supporting EBM from a diverse pool of independent physician reviewers. Among other goals, the IRO attempts to:

- Facilitate access and sharing of EBM literature and sources.;

- Incorporate EBM into a UM system that uses hundreds of independent practitioners.

- Assist the physician reviewer to interdigitate EBM into UM determinations.

- Ensure reports of the similar quality from diverse participants.

- Maximize communication among physician reviewers regarding EBM and UM report requirements.

- Nurture and grow EBM-UM techniques within the internal process and among geographically dispersed physician reviewers.

- Develop UM technology to provide new approaches to problem solving.

- Maximize the use of technology by all participants to produce EBM-centered reports within extremely short time constraints.

To address these challenges, and to determine the impact of incorporation of EBM guidelines on physician reviewer behavior, our organization created strategies in five targeted areas: 1) access to evidence-based literature; 2) a standardized report format; 3) quality assurance; 4) performance feedback to physician reviewers; and 5) a comprehensive enterprise content management system.

Access to Evidence-Based Medicine Literature

During 2002, our organization began to assemble a library of EBM literature quoted by reviewers and supplied by clients to provide resources for physician reviewers. Providing literature was seen as an effective mechanism to improve physician productivity and timeliness. The EBM resources included clinical guidelines, specialty-generated position papers and articles from peer-reviewed medical journals. Once identified, this literature is inventoried and electronically maintained by a research department. It is kept current by a research librarian with a healthcare background.

For utilization determination requests, the research department is responsible for the compilation of files of pertinent literature to accompany the medical case records forwarded to physician reviewers. Reviewing physicians are also required to provide the IRO with citations for relevant literature that was used to support their determinations. Thus, new references are continually added to the IRO’s EBM library for use in future similar review cases. This system allows an information exchange among all parties involved in the review activity: client, IRO, and physician reviewer. The intent is to ensure that patient healthcare services are reviewed under best practice parameters discernible to all parties.

Standardized Report Format

The use of a standardized report format has roles in the training and evaluation of physician reviewers. A meaningful and comprehensive utilization management report must contain a set of vital elements to assure a fair assessment of each healthcare request. A standard format, given to the physician reviewer with each assigned case, reinforces the required report sections and content. A quality UM report includes a rationale that documents the application of EBM criteria to patient-specific findings to reach a definitive conclusion as to the medical necessity of the requested service. Providing a guideline to reviewing physicians facilitates the inclusion of EBM while documenting the physician reviewer’s logical decision pathway. The final UM report documents the procedural request, relevant patient-specific clinical information, the medical necessity determination, the supporting rationale, and relevant literature citations. The rationale must demonstrate an attribute termed “interdigitation,” which is defined as “the documentation of the application of best practice standards to the patient’s specific situation to reach a medical conclusion.”

Providing a standard format enables each physician to reach the same level of quality in the utilization report. Following the standards established by URAC, this ensures that similar information is used to reach the medical necessity determination. Physician reviewers are kept informed of the expected elements of a quality report through the report format guidelines and through a feedback program. The inclusion of EBM literature as supporting documentation is reinforced as a known required component. Quality-assurance activities can easily focus on checking for required elements within a consistent framework, thereby streamlining the assessment and scoring process.

Quality Assurance

Quality assurance (QA) activities focus on the quality of the utilization review product (the final report that is sent to the client) and the performance of the reviewing physician. QA for the final report is verified at three distinct levels of the process: transcription, review by a technical writer, and final review and release by a medical director. Specific performance variables are scored for the physician and for the final report. Variables that were measured included timely submission, following directions, answering posed questions, providing appropriate and relevant content, documentation of rationales, logical integrity, and EBM citations. The highest score is achieved by the report that meets all requirements and interdigitates evidence-based medicine into the rationale. The QA assessment is captured in the database as the foundation of the physician feedback system.

Performance Feedback to Physician Reviewers

A feedback system is essential to an integrated review process and the continued education of physician reviewers. Feedback not only assesses the physician’s individual performance, but also reinforces the requirement for EBM and the need to maintain current knowledge in the medical specialty. A feedback program must provide information on each completed report with details on the level of performance. This provides the reviewer insight into specific deficiencies and increases awareness of reporting requirements. Non-submission or selection of appropriate EBM criteria is a vital scoring element.

Comprehensive Enterprise Content Management System

To enable management and rapid exchange of the information processing, we developed an enterprise content management system to encapsulate utilization management data into a single repository from which content is easily managed among internal and external users. The data warehouse includes all clinical, demographic, QA, EBM, and case-flow data. The infrastructure permits fast and easy exchange of information among authorized users while limiting access to unauthorized users in accordance with HIPAA regulations (www.hipaacomply.com).

Technology in place includes secure email, online report access, automated digital transcription, and structured repositories for UM case data and EBM citations. Secure Web-based portals are vital for rapid information exchange. Physician reviewers can receive case material and relevant EBM materials through secure email, minimizing transmission time and maximizing the clarity of the materials sent. This process allows photographs and most X-rays to be transmitted. The information system enables the rapid flow of UM clinical data from clients through the IRO to appropriate physician reviewers and back to the client within a secure environment. Such an information system is essential to the ability to exchange information and resources and produce a quality EB-UM report within tight turnaround times.

Results

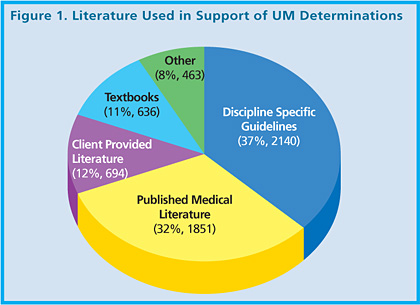

Internal analysis indicates that most physician reviewers rely on specialty-specific papers or other specialty-generated documentation as the most common source for EBM literature. Cited references from 2,600 reviews were collected and analyzed for the category and frequency of references used in medical determinations. The four most often quoted include: 1) disciple specific guidelines written by specialty organizations such as the American College of Cardiology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2) published literature from peer-reviewed medical journals; 3) literature (including plan language) provided by the client; and 4) medical textbooks. Other sources, such as Medicare contractor guidelines, continuing medical education course material, and conference handouts, were cited less often (Figure 1).

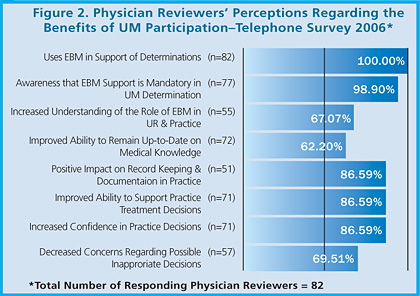

We surveyed physician reviewers. They have responded positively to the physician reviewer feedback system and reported that participation in utilization management activities has impacted their own practice of medicine and improved their ability to support requests for healthcare services for their patients. These anecdotal reports prompted this IRO to initiate a telephone survey to quantify the impact of its strategies on the physician review panel.

To test our hypothesis, we performed a telephone survey of 144Ýactively practicing physicians who completed more than 10 reviews in 2005. The survey confirmed our suspicions (Figure 2). The response rate for the survey was 57%. While all respondents reported consistent use of EBM in their UM reports, only 94% were aware that the submission of EBM literature was required to support their medical determinations. 88% agreed that participation as a physician reviewer has helped them keep current on new treatments and stay connected with the medical community for improved patient care. 87% agreed that UM activities helped them recognize practice-relevant EBM and incorporate new medical knowledge in their own practice. Finally, 87% of the respondents agreed that UM participation increased their professional confidence in making recommendations and practice decisions that are based on the most current evidence available.

Based on the available internal data analysis and survey results, physicians find that participation in utilization management activities affords opportunities to keep abreast of changing medical information and is seen as an adjunct to professional experience in developing evidence-based practice patterns.

Acknowledgement

We thank Jill A. Anderson, R.N., and Brian D. LaTour, B.A., for their technical support and commentary.

Linda Gordon Sheff is vice president and CAO of Physicians’ Review Network, Inc. (PRN) and a graduate of S.U.N.Y. at Buffalo. Her professional experience includes laboratory and hospital administration with a focus on utilization management since 1989. Sheff became an ABQAURP Diplomate in 1992. She may be contacted at lsheff@prniro.com.

Albert Sheff has served as president and CEO of PRN since 1995. Sheff is a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association with career experience in quality assurance, utilization management and governmental, correctional and private healthcare administration. Sheff has been an ABQAURP Diplomate since 1991.

Danette Dehnicke graduated from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine and Health Sciences. Her current position at PRN is research administrator.

David Doperak earned his doctorate in chiropractic from Life University in Marietta, Georgia. He currently serves PRN as an associate clinical director.

Joan Livesay is corporate counsel to PRN and a graduate of WillametteÝUniversity.Ý She has been involved in law impactingÝhealthcare and utilization management since 1995.

References

Bates, D. W., Kuperman, G. J., Wang, S., et al. (2003). Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: Making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(6), 523-530.

Bhandari, M., Zlowodzki, M., & Cole, P. A. (2004). From eminence-based practice to evidence-based practice, a paradigm shift. Minnesota Medicine, 4, 51-54.

Coomarasamy, A., & Khan, K. S. (2004, October 30). What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. British Medical Journal, 329(7473), 1017.

Craig, J. C., Irwig, L. M., & Stockler, M. R. (2001, March 5). Evidence-based medicine: Useful tools for decision making. Medical Journal of Australia, 174(5), 248-253.

Davis, D., Evans, M., Jadad, A., Perrier, L., Rath, D., Ryan, D., Sibbald, G., et al. (2003, July 5). The case for knowledge translation: Shortening the journey from evidence to effort. British Medical Journal, 327, 33-35.

Dawes, M., Summerskill, W., Glasziou, P., et al. (2005, January 5). Second International Conference of Evidence-Based Health Care Teachers and Developers. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Medical Education, 5(1), 1.

Guyatt, G. (1991). Evidence-based medicine. ACP J Club (Annals of Internal Medicine), 14(suppl 2), A-16.

Guyatt, G., Cook, D., & Haynes, B. (2004). Evidence based medicine has come a long way. British Medical Journal, 329, 990-991.

HIPAA Comply. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 HIPPA. Public Law 104-191 (H.R. 3103). Accessed March 1, 2005, at www.hipaacomply.com

HMO Settlements. (2000, October 23). In re Managed Care Litigation, Master File No. 00-1334-MD-MORENO which includes Shane, et al. v. Humana, Inc., et al., Case No. Civ. 04-21589-CIV-MORENO and Thomas, et al. v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, et al., Case No. 03-21296-CIV (S.D. FL. 2005). www.hmosettlements.com

Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, 2, 403-404

Lomas, J., Culyer, T., McCutcheon, C., & McAuley, L., & Law, S. (2005, May). Conceptualizing and Combining Evidence for Health System Guidance. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. www.chsrf.ca/ other_ documents/pdf/evidence_e.pdf

McKibbon, K. A. (1998). Evidence-based practice. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 86(3), 396 — 401.

Montori, V. M., & Guyatt, G. H. (2001). What is evidence-based medicine and why should it be practiced? Respiratory Care, 46(11), 1201-1211.

Norman, G. R., & Shannon, S. I. (1998). Effectiveness of instruction in critical appraisal (evidence-based medicine) skills: A critical appraisal. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 158, 177-181.

Saarni, S. I, & Gylling, H. A. (2004). Evidence based medicine guidelines: A solution to rationing or politics disguised as science? Journal of Medical Ethics, 30, 171-175

Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. A., et al. (1996, January 13). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, 312(7023), 71-72.

Straus, S. E., & Sackett, D. L. (1998). Using research findings in clinical practice. British Medical Journal, 317, 339-342.

University Health Network, www.cebm.utronto.ca/glossary. Accessed March 1, 2006.

URAC Amends Utilization Management Standards to Align with Federal Regulations. April 15, 2003. www.urac.org/news. Accessed March 1, 2006.

US Department of Labor, Pension and Welfare Benefits Administration. Federal Register 29 CFR Part 2560, Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974; Rules and Regulations for Administration and Enforcement; Claims Procedure; Final Rule. Nov. 21 2000: 70247-9.

Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC). (2005). The Utilization Management Guide (3rd ed.). 94-262.

Von Segesser, L. K. (2003). Writing off evidence in evidence-based medicine? Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, 2, 403-404.