Daily Check-In for Safety: From Best Practice to Common Practice

September/October 2011

Daily Check-In for Safety: From Best Practice to Common Practice

0759 hours, 58 seconds: The plan-of-the-day (POD) meeting begins at Black Fox Nuclear Power Plant. The plant manager nods to the shift supervisor. The shifter reports on plant status and reviews plant risk level (at “yellow” today) and contributing conditions. He concludes by reporting zero worker injuries in the last 24 hours. “Well done and to goal,” comments the plant manager. The work-week manager gives a status of routine work items for the week and a detailed report on critical conditions contributing to the elevated risk level. Routine reports follow: chemistry levels, operations priorities, and any temporary modifications or operator workarounds. All are reported by exception only – no need to discuss the details here as long as the plan is sound and progressing on schedule. From time to time, the plant manager asks a question or comments, “What is the cause of the variance…if there is any doubt, we’ll shut the plant down until we understand the nature of the problem…plan the work, work the plan. Quality Assurance reviews the Top 10 problem list, pointing out a missed due date on an action plan.” (The plant manager frowns and requests a meeting with the plan owner following the meeting.) The shift supervisor summarizes next steps for the day. The plant manager then reminds all: “Work safe and work smart.” The POD meeting ends at 0828, and everyone goes out to accomplish the work of the day.

In the nuclear power industry, knowing the status of plant operations and early identification of potential problems is safety critical. At nuclear generating stations across the country, like the Black Fox plant (a pseudonym), each day begins with a plan-of-the-day meeting of plant leaders. A typical agenda includes a review of emergent safety issues, status of the plant’s Top 10 problem list, routine reports, and priorities for the day. The meeting is a leadership method for providing awareness of front line operations, identifying problems, assigning ownership for issue resolution, and ensuring common understanding of focus and priorities for the day.

In Managing the Unexpected, Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) describe five defining characteristics of high reliability organizations: sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise. All five characteristics can be found in nuclear power’s Plan of the Day meeting. In fact, all high-reliability organizations have some variation of a Plan of the Day meeting. Many healthcare organizations are applying best practices from high-reliability industries, such as aviation and nuclear power, to improve patient safety and clinical outcomes. Let’s look at the application of this high-reliability best practice in the healthcare industry.

Daily Check-In for Safety – Healthcare’s Plan of the Day Meeting

The plan-of-the-day equivalent in healthcare is the “daily check-in” (DCI) for safety. DCI is a deliberate, focused report and conversation among leaders about safety events and safety risks.

In this real-time risk assessment—reflecting the words of Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy” (Rockwell, 2002)—the leaders in charge must concern themselves with the details. If they do not consider them important, neither will their subordinates. And, leaders in the field must face the facts and make the necessary changes to prevent harm to patients, families, and workers.

Commonly, DCI is a 15-minute meeting of the senior leader with all department leaders of the organization, and a three-point agenda is used:

- Look back: Significant safety or quality issues from the last 24 hours

- Look ahead: Anticipated safety or quality issues in next 24 hours

- Follow-up: Status reports on issues identified today or days before

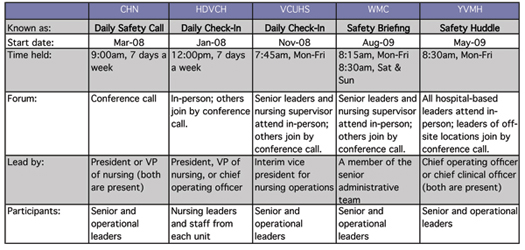

Healthcare organizations across the country are initiating DCI as a high-reliability leadership method. Five organizations, all practicing DCI for at least 1 year, share their insight and experiences in this article. The organizations included:

- Community Hospital North of Community Health Network (CHN)—a 289-bed acute care hospital in Indianapolis, Indiana

- Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital of Spectrum Health (HDVCH)—a 212-bed pediatric hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Virginia Commonwealth University Health System (VCUHS)—a 779-bed academic medical center in Richmond, Virginia

- Wyoming Medical Center (WMC)—a 207-bed acute care hospital in Casper, Wyoming

- Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital (YVMH)—a 225-bed acute care hospital in Yakima, Washington

In all five organizations, a senior leader facilitates the meeting, and other senior leaders and all operational leaders participate. The meeting occurs in the morning and is scheduled for 15 minutes. Three organizations—Community Hospital North, Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, and Wyoming Medical Center—hold DCI 7 days a week.

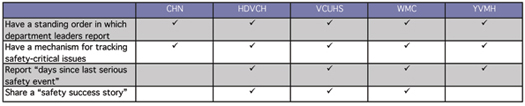

Most organizations have a fixed order in which participants report, with an “everyone checks-in” expectation (no report by exception). When safety-critical issues are identified, all organizations have a mechanism, such as a rapid-response list for urgent issues and/or a top-10 safety list for longer-term issues, for tracking issues, and issue resolution. “If the issue requires follow-up, it is written on a white board in the administrative conference room and is addressed in the safety briefing the following day,” says Vickie Diamond, president and CEO of Wyoming Medical Center. “The issue stays on the white board until it has been resolved.” Wyoming Medical Center also begins DCI each day by sharing a “safety success story” of an individual who practiced a behavior expectation for error prevention and made a difference. Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital and VCU Health System report “days since last serious safety event” as a means of making explicit what traditionally has been an implicit daily goal—creating a safe day—by focusing the staff today on “What will it take today?” to make this a safe patient care day.

A High-Leverage Leadership Method

Bill Corley, president emeritus of Community Health Network views daily check-in as “the most transformational leadership practice I’ve experienced.” DCI indeed is a high-leverage leadership method—one that requires little time and, when practiced well, has high impact on influencing organizational performance. In fact, DCI doesn’t take time, it saves time for leaders.

Shared Situational Awareness

A chasm exists in many organizations between the blunt end and the sharp end of the system.1 Leaders at the blunt end lose sight of realities and challenges at the front line. At the sharp end, risk becomes normalized and workers desensitized to the high-consequences of failure and the impact that local actions have on the system as a whole. DCI closes the blunt-end/sharp-end disconnect by creating shared situational awareness.

For the senior leader, DCI provides awareness and real-time understanding of what’s happening at the front line. “Daily check-in has become a quick and efficient way to take the pulse of the organization,” observed Shirley Gibson, interim vice president for nursing operations at Virginia Commonwealth University Health System. For operational leaders, DCI enables them to begin their day with an awareness of what’s going on in other areas.

“As other leaders are reporting, I’m listening to hear if what they are presenting affects my area and how. The call becomes my opportunity to be proactive in my thinking and to speak out on how to resolve the issue,” commented a leader who participates in Community Hospital North’s daily safety call.

Heightened Risk Awareness

When an event occurs, risk awareness within the organization is at an all-time high. Attention is given to managing behaviors and processes to prevent event recurrence. As time passes, a natural decay in memory sets in. This is depicted as the “forgetting curve.”2 The rate of forgetting is accelerated by overconfidence following periods of successful operations, turnover in the organization, and diversions and distractions of projects and priorities. DCI provides a forum for talking about risk every day, keeping it top of mind.

All organizations reported increased risk sensitivity of leaders since implementing DCI. Here is one DCI story that demonstrates this. During a recent safety huddle at Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital, the nursing supervisor shared that a physician called to admit a patient and had requested a bed with telemetry monitoring. Upon learning that there were no monitored beds available, the physician downgraded the admission request to a general medical bed. Shortly after the patient arrived, care team members assessed that the patient needed to be transferred to the ICU. The nursing supervisor reported the situation with a renewed recognition of safety risk: “I should have thought and questioned the physician, ‘If the patient needed monitoring 30 seconds ago, why don’t they need monitoring now?’ I’ll think about that differently next time.” Sharing this as a threat to safety in the safety huddle contributed to heightening the risk awareness of other leaders in thinking about parallel situations that occur in their areas.

“The call has led to better realization of clinical safety issues by non-clinical folks and vice versa. There are a thousand ways to hurt a patient, and any one person probably only knows a handful of them. Talking and thinking about them as a group helps raise everyone’s awareness of all types of risks and dangers,” shared an operational leader and participant in the daily safety call at Community Hospital North.

Early Identification and Resolution of Problems

A good leader analyzes events of harm to determine causes and corrective actions to prevent recurrence. A great leader identifies the metaphorical holes in the Swiss cheese before system weaknesses aggregate as an event.3 DCI promotes a questioning attitude about existing issues and evolving conditions that threaten safe, quality outcomes.

A resounding benefit expressed by all organizations is early identification and rapid resolution of issues that could impact patient care. “There is a shared sense of urgency for finding and fixing,” says Susan Teman, manager of patient safety and quality at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. “And the credibility of leadership has risen. Staff know that daily check-in occurs, and they have renewed confidence that safety issues are being addressed.”

DCI promotes systems thinking, the hallmark of high-reliability organizations. Systems thinking focuses on understanding the structures in a system and how those structures guide the actions and interactions of the people who work in the system. Recognizing this interconnectedness between and among structures and people in a system is fundamental to the ability to prevent, detect, and correct problems that occur in an organization.

“Silo thinking can be devastating in a high-consequence industry,” says Russ Myers, chief operating officer of Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital. “After implementing the safety huddle, silos in our hospital are beginning to disappear. Department leaders share ideas and resources, and they often stay after safety huddle to begin problem solving immediately. Problems are resolved efficiently.”

Here is one example of this from Wyoming Medical Center: “When the nursing supervisor reported that the patient transport service was short-staffed, the director of the operating room immediately volunteered to have her staff come to the patients’ rooms and take over transport of the patients to surgery for that day to take the burden off the transport staff and to maintain the surgical schedule. There is a strong sense of teamwork and accomplishment when an issue is brought up during the safety briefing and participants are able to come together to resolve the issue, sometimes while on the call.”

Accountability for Safety

DCI fosters internal transparency and accountability for safety. “Before, event reporting lived on paper. Now, leaders have to own the events that happen on their watch…and on our watch,” says Sandy Dahl, chief clinical officer at Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital. “Rather than being a number on a page, a leader has to say, ‘A patient on my unit has VAP (ventilator associated pneumonia).’”

“Talking about perfect care has become easier,” says Barbara Summers, president of Community Hospital North. “We sincerely believe that zero is possible and achievable. We are more aggressive now in our leadership for zero events of harm. At Community, this is the foundation of what we call the ‘exceptional patient experience.’”

The Responsibility of the Senior Leader: Set the Tone and Accelerate the Pace

Daily check-in is not hard to do, however, leaders at all the organizations certainly encountered challenges in implementing DCI. The top three challenges cited by the organizations included:

- Overcoming resistance to “everyday, everyone”—as the leader, emphasize the role that every leader plays in problem solving and in learning from the problems experienced by others.

- Keeping it focused on safety—as the leader, course correct when unrelated issues or conversations emerge.

- Keeping it brief—as the leader, coach on concise briefs and off-line problem solving.

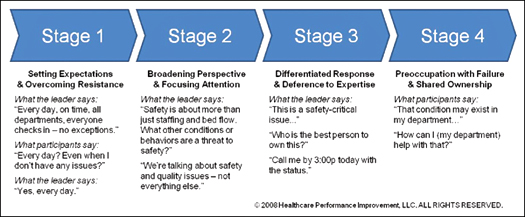

Once DCI is initiated, high-reliability thinking doesn’t just happen; it evolves over time. And leaders determine the pace. Leadership for high reliability requires two things: 1) a risk-averse mindset (how leaders perceive situations and look for risk) and 2) risk-averse actions (what leaders say and do to promote and influence individual and team behaviors that prevent failures).

The following are questions a leader can ask during DCI to promote a risk-averse mindset and risk-averse actions in others:

- How do you know you had no problems in the past 24 hours?

- What immediate, remedial actions did you take?

- Is this happening in other places? Could this happen in other places?

- What other areas does this issue impact?

- How are you preparing your team for that high-risk task?

- What error prevention behaviors should be used?

When a mistake, event, or high-risk condition is reported, choose your words carefully. Your tone and the words you say make it either more likely or less likely that the individual – and others who observe your response – will speak up in the future. When you hear about a mistake or an event, let your first words be, “Thank you.” Then say, “Lets’ understand how that happened.”

When a deficiency is identified that could compromise safety, the role of the leader is to convey a sense of urgency and priority for issue resolution: “That’s a safety critical issue that requires a rapid response. Who will own the issue? Let me know if you encounter any difficulties, and page me by 3 this afternoon with a status report.”

All organizations practicing DCI report an evolution in high-reliability thinking of leaders and participants. The evolution toward high-reliability thinking is shown in Figure 1.

“It’s a never-ending, ever-evolving process,” says Barbara Summers. She continually looks for ways to optimize DCI and keep it fresh over time. On Community Hospital North’s daily safety call, several leaders each day conclude their routine check-in reports by saying, “And today is my day to report.” As a practice recently implemented, Summers assigned leaders to a rotating schedule of reporting a specific thing they are doing to keep safety top of mind in their department.

As for a nuclear power practice that could be applied to healthcare’s DCI, the senior leader can give operational leaders a “What would you do if…” scenario or a safety condition to look for in their departments and then randomly call on one leader to report on their findings the next day!

Oh yes…across the organizations responding to the survey, what is the number-one focus in taking DCI to the next level? The answer: engaging physician leaders in routine participation in DCI.

Measuring the Impact

In “Executive Leadership Development in US Health Systems” Dr. Ann McAlearney (2010) comments, “The lack of evaluation standards and general difficulty reported around [Executive Leadership Development] program evaluation highlight the opportunity…to focus on developing consistent evaluation metrics and attempting to explicitly tie program results to organizational performance.”

The same challenge may be true in measuring the impact of DCI on safety and overall performance excellence. DCI is one of many things that leaders do to deliver on safety and overall performance excellence. So the direct impact indeed is difficult to measure. With that said, organizations in this survey have reduced their serious safety-event rate (SSER)4 by 39% to 75% since beginning efforts to forge a reliability culture that drives results in safety and overall performance excellence.

Specific to daily check-in, two of the organizations have measured perceptions of operational leaders regarding impact of DCI on safety. VCU Health System conducted a survey of DCI participants 3 months after implementation. 74% of respondents indicated a “somewhat-to-significant” impact of DCI on safety in their areas. At the 2-year mark after implementation, Community Health Network conducted a survey. On a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = high added value—best thing we’ve done for safety, to 5 = redesign ASAP – this call adds no value), operational leaders responded with an overall score of 1.35.

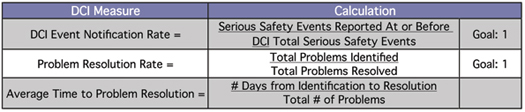

In addition to perceptional measures, the following are offered as specific process measures of DCI:

“Just Do It!”

These exact words were listed by organizations when asked to provide advice to leaders who may consider implementing a daily check-in. Here’s what else they had to say:

- Be inclusive; whether in a clinical or non-clinical role, everyone supports safety.

- Work hard to make the meeting non-threatening and systems-focused.

- Start and commit; improve the process along the way.

- Make it mandatory; the meeting that trumps all others.

- Lead from the top; a senior leader facilitates and all senior leaders participate.

What differentiates leaders and high-reliability leaders? Habits. High reliability leaders adopt best practice leadership methods as their day-in and day-out common practices. At one time or another every leader has held a meeting like daily check-in. When adopted and practiced as a leadership method, daily check-in serves as a high-leverage technique in fostering a reliability culture that drives results in safety and overall performance excellence.

Carole Stockmeier is the managing partner and chief operating officer of Healthcare Performance Improvement (HPI). HPI is a consulting firm that specializes in improving human performance in complex systems using evidence-based methods derived from high-consequence industries. Prior to the formation of HPI, Stockmeier served as the director of safety & performance excellence at Sentara Healthcare. She holds a bachelor-of-science degree in public health from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a master’s degree in health administration from the Medical College of Virginia of Virginia Commonwealth University. She is certified as a manager of quality and organizational excellence by the American Society for Quality. Stockmeier may be contacted at carole@hpiresults.com.

Craig Clapper is a founding partner and the chief knowledge officer of HPI. Clapper has 25 years of experience improving reliability in nuclear, power, transportation, manufacturing, and healthcare. He holds a bachelor-of-science degree in nuclear engineering from Iowa State University and a professional engineering license in mechanical engineering from the State of Arizona. He is certified as a manager of quality and organizational excellence from the American Society of Quality. Clapper may be contacted at craig@hpiresults.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend appreciation to the following individuals for their contributions:

Community Health Network: Barbara Summers, president, and Trudy Hill, patient safety officer

Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital: Thomas Peterson, MD, executive director of patient safety & quality; and Susan Teman, BSN RN, manager, patient safety and quality

VCU Health System: Shirley Gibson, RN, MSHA, interim vice president for nursing operations; L. Dale Harvey, MS, RN, director for performance improvement; and Jenifer K. Murphy, MHA, operations manager for performance improvement

Wyoming Medical Center: Vickie Diamond, president & CEO

Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital: Sandy Dahl, chief clinical officer; and Russ Myers, chief operating officer

American Society for Quality: The authors also would like to thank ASQ for its support in the development of this manuscript.

References