Communication, Collaboration and Critical Thinking = Quality Outcomes

November / December 2007

Communication, Collaboration and Critical Thinking = Quality Outcomes

![]()

You are a nurse on a busy medical-surgical unit, it’s Friday night, and you have just come on duty. You check your patients and become concerned about Mr. Z, who is scheduled for orthopedic surgery tomorrow. His case just does not seem as simple as the previous nurse indicated. Her report was, “This is a 55-year-old male, weighing 285 pounds, who fell at home and heard a loud pop in his ankle. He had previous hardware in that ankle and was admitted through the emergency department. Orthopedics saw the patient and ordered a morphine pump for pain. Surgery is planned for morning. Preoperative labs and x-rays have been done and the consent is signed. The patient was on the blood thinners for a history of blood clots in his lungs that occurred after his previous ankle fracture surgery. Although his blood thinners are on hold for surgery, his blood is still mildly thinned. His other past history is significant for emphysema. He still smokes. He is on low-flow nasal oxygen.”

When you check the patient again, he is responsive, but very groggy. He has been up on the unit for about 4 hours. The morphine pump was started upon arrival. He denies pain. His heart rate and blood pressure are unremarkable. His respirations are shallow. His oxygen saturation is low at 84%, when it should be greater than 90%. Respiratory therapy comes and turns up the oxygen flow. Eventually, his oxygen saturation rises to 93%. You contact the attending physician to report the changes in the patient’s condition. The doctor is not familiar with Mr. Z. He was newly assigned to the case when the patient came to the ER. You know the preoperative chest x-ray was normal. The attending physician believes that Mr. Z just had too much narcotic and tells you to hold the morphine pump and “keep an eye on the patient.” You place a continuous oxygen monitor on Mr. Z’s finger so at least you will know if his oxygen level drops again. You feel a little uneasy but…. “At least the doctor knows.”

At 6:30 am, as you are preparing to give shift report, the patient care technician rushes out to tell you that she is having difficulty arousing Mr. Z. Entering his room, you find him with shallow respirations. You end up calling respiratory therapy and eventually anesthesia because the patient requires a respirator. He is transferred to ICU. Of course, the surgery has to be cancelled.

That scenario is not one that any healthcare team would like to encounter. Fortunately, there are ways to minimize such events. At Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital, we wanted to improve outcomes on our medical and surgical care units. Simultaneously, we wanted to improve nursing satisfaction and retention. In 2004, we embarked on a redesign project for our medical/surgical nursing division with the goal of uncovering weaknesses and opportunities to improve care and satisfaction. As part of this project, we conducted a survey of key physicians and nurses to identify issues they perceived as having a major impact on care. Our survey revealed the following:

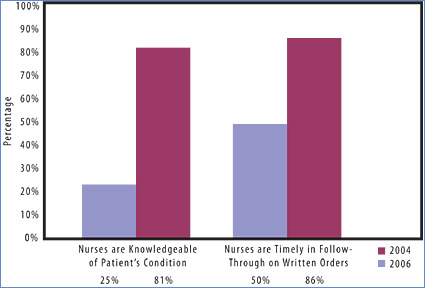

- Only 25% of physicians felt that the nurses were knowledgeable about the patient’s condition and provided physicians with pertinent information when reporting changes in patient conditions.

- Only 50% of the physicians surveyed felt that RNs were timely in their follow through on written orders.

- 33% of the surveyed physicians felt that improved communication would enhance care and improve outcomes.

- 17% of the nursing staff felt that poor reporting and communication were barriers to efficient patient care.

- 17% of physicians noted that joint rounding between the physician and nurse would improve the discharge process.

These responses indicated three areas of perceived deficiency that required attention:

Critical-thinking skills of nurses.

![]()

- Communication between physicians and nurses.

- Collaboration and collegiality between physician and nurses.

To improve care, intuition tells us that all three of these areas are worthy of focus. In addition, each one is substantiated by the literature and national patient safety initiatives.

Critical thinking is defined in the nursing literature as “a certain mindset or way of thinking, rather than a method or a set of steps to follow. Critical thinking is clear thinking that is active, focused, persistent, and purposeful. It is a process of choosing, weighing alternatives, and considering what to do. Critical thinking involves looking at reasons for believing one thing rather than another in an open, flexible, attentive way” (Kyzer, 1996). To have critical thinking skills is “to think (and perform) in such a way that staff will see patterns and ramifications beyond a present issue; that they can focus on the goals that they and their patients seek; and that they are able, in a creative and continuous manner, to make good decisions and follow up actively on problems” (Hansten & Washburn, 1999).

According to Hansten & Jackson (2004), use of critical-thinking skills should lead to:

- Improved patient care as measured by fewer incidents (falls, medication errors, omissions), decreased length of stay, fewer return visits to the hospital, emergency department, or intensive care unit.

- Better patient satisfaction related to appropriate discharge instructions, attention to patient priorities while under care of an RN, smooth transitions from one point of care to another.

- Increased resolution of problems, care issues, system glitches.

- Less blaming, more “How can I fix this problem?”

- Improved staff morale and less turnover in all disciplines as interdisciplinary teamwork improves and as all workers feel more empowered to effect change both within the patient care realm and with organizational systems (p.323).

Additionally, the benefits of nursing staff that “get it” and are able to utilize critical thinking skills are tremendous. When a nurse has the ability to analyze a patient’s changing condition and act appropriately, the level of care and patient outcomes improve.

Communication is believed to be the root cause of 60 to 70% of sentinel events (Joint Commission, 2002). Physicians and nurses are trained to communicate differently, which sets up the potential for miscommunication. This factor illustrates the necessity of optimizing communication among the multidisciplinary members of the healthcare team. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) identified communication as a focus to improve outcomes. The 2003 IHI initiative, “Transforming Care at the Bedside,” identified that specific communication models support consistent and clear communication among caregivers and dramatically improve care and staff satisfaction on medical/surgical units.

SBAR is an example of a structured communication technique that helps clinicians share a mental model of a patient’s clinical condition. Developed by Michael Leonard, MD, director of Patient Safety for Colorado Permanente Medical Group and Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, the SBAR acronym stands for Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation and provides a framework for effective communication among members of the healthcare team.

In July 2002, the Joint Commission approved its first set of National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs) designed to improve the safety of patient care in healthcare organizations. The 2003 goal of “improving the effectiveness of communication among caregivers” sharpened the communication focus. Taking things even further in 2006, healthcare institutions were directed to “implement a standardized approach to ‘hand off’ communications, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions.” Communication continues to be the primary target for current Joint Commission patient safety initiatives.

Collaborative/collegial relationships between nurses and physicians yield better patient outcomes, as substantiated in the nursing literature. According to Schmalenberg and Kramer (2005), “MD/RN collaboration is associated with decreased patient mortality, fewer transfers back to the ICU, reduced costs, decreased length of stay, higher nurse autonomy, retention, nurse-perceived high-quality care, and nurse job satisfaction.” Larrabee (2003) found that positive MD/RN relationships were a contributing factor to improved nursing job satisfaction and retention.

In addition, negative interactions between physicians and nurses should decrease as their collegiality and mutual respect improves. Rosenstein and O’Daniel (2005) surveyed 1,509 physician, nurses and administrators in 50 VHA hospitals. The aggregate of the three groups’ responses indicated a significant percentage had, at some time, witnessed negative (or what they considered disruptive) behaviors on the part of both physicians (74%) and nurses (68%). Although more than half of the respondents estimated that the actual percentage of physicians and nurses that demonstrate this pattern was low (1 to 3%), the majority believed that such behaviors increased stress and frustration for both nurses and physicians. At the same time, they felt, it decreased concentration, communication, collaboration, information transfer, and workplace relationships for the two groups overall. The end result, in their opinion, was a negative impact on the quality of patient care and patient satisfaction. These factors reinforce the need to continuously cultivate high quality MD-RN relationships.

A Program to Improve Healthcare Delivery

Combining our survey results with the knowledge from the literature and patient safety initiatives, the med-surg redesign team set out to develop an action plan. The chief nursing officer and the director of nursing for the division, sought out a physician champion and a group of lead advanced practice nurses (APNs) that were actively engaged in care on the various nursing units. Together they brainstormed a method to improve three target areas: communication, collaboration and critical thinking skills. a new program coined “Communication, Collaboration and Critical Thinking = Quality Outcomes” (CCC) was created.

The mission of CCC was to achieve an even higher level of patient care, safety, quality outcomes, and overall satisfaction by utilizing strategies that cultivate the MD/RN relationship while improving critical thinking skills. The strategy of CCC was physicians and nurses collaborating to collect, communicate, and critically analyze clinical patient information to set the course of care.

The newly formed CCC team came up with a three-component program:

- Interactive CCC case-study presentations held three to four times per year by an APN-MD team in a roundtable discussion with active participation from MDs and RNs from the med-surg division.

- Formal and informal physician/nurse rounding integrated into daily activities as well as the new nurse orientation program, continuously encouraged through role modeling by APN leadership.

- Development and implementation of the “Share a Teaching Moment” campaign, where MDs and RNs are encouraged to share clinical pearls rather than just orders.

Case Study Program

The CCC case study program is offered three to four times per year to the medical and nursing staff, using real patient case studies to discuss the evaluation, differential diagnosis, and plan of care from both the medical and nursing perspective. These forums are designed to improve not only critical-thinking skills of nurses, but communication and collaboration between healthcare workers, which reinforces quality patient outcomes. The case studies incorporate clinical knowledge, as well as highlighting and reinforcing key components of safety initiatives of our organization and other worldwide healthcare quality organizations. Currently we have featured aspects of the Advocate Health Care system-wide “Culture of Safety” as well as JCAHO and IHI initiatives, such as handoff communication and medication reconciliation.

In addition, compliance with best practices, as defined in the Medicare core measures bundles for conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and surgical care infection prevention care, is embedded into each presentation. The case studies are presented in a relaxed, open environment, which promotes relationship building between the participants. This type of collaboration models behavior that we endeavor to carry into daily care at the hospital.

Participants are surveyed following every session for feedback regarding cases, room set-up, and presentation style. Changes are made as a result of the recommendations offered. Presentations have become more sophisticated with incorporation of x-rays, CT scans, ultrasounds, echocardiograms, and angiograms. Presentation style has advanced from a single physician to a panel of physicians from various specialties. We are progressing towards having case studies presented by staff RNs in collaboration with physicians. More than 100 participants have attended each program, and More than 80 physicians and 250 nurses have attended at least one CCC case study presentation. Other disciplines such as respiratory therapy and physical therapy have attended, as have the CEO and CFO of the hospital.

Participants have made very positive comments on their evaluations:

- “This program was very informative and interactive. Great MD participation!”

- “I appreciate doctors and nurses sitting together, learning together.”

- “I am a new employee, and this session was great for me to experience team collaboration and to see ‘the big picture.'”

Physician/Nurse Rounding

The “Rounding” and “Teaching Moment” aspects of the program were created in order to formalize the integration of behavior patterns learned through the case study presentations into the daily practice on the nursing units. We wanted these behaviors to happen every day on every nursing unit, not only when scheduled case studies were presented. Unit-based APNs, the unit managers, and the charge nurses continually encourage physician/nurse rounding on both a formal and informal level. Nurses are encouraged on a daily basis to “see the patient with the doctor,” give valid information to the physician, and at the same time, ask important questions about care. Formal rounding is incorporated into unit orientation programs and the new graduate residency program, where a new hire is given the opportunity to “round with a doctor” towards the end of their orientation. This helps both disciplines get to know each other and helps the nurse “see it through the doctor’s eyes” in order to enhance communication when they need to work together to solve specific patient care issues.

Share a Teaching Moment

The “Share a Teaching Moment” campaign is an initiative designed to encourage the sharing of information among caregivers. Initially, we had a 1-week “blitz,” which introduced and heightened awareness of this concept. Staff kept notes and nurse managers sent handwritten acknowledgements to each MD who shared a teaching moment. Unit-based APNs use this approach to encourage and promote a questioning and inquisitive atmosphere. Recently, the nursing shared governance awarded the 2007 Friend of Nursing award to the physician that shared the greatest number of teaching moments.

Additional Projects

Two additional projects were designed to spread the CCC concept: placement of a designated communication sheet in the patient chart and a program for nurse residents called “Nurse as the Manager of Care.” No longer do the charts have wrinkled “post-its” all over the order sheets and progress notes. One brightly colored sheet is place in a designated area of the chart for the nurse to leave notes for the MD regarding noncritical requests for orders or patient requests. The final aspect has been the participation of an MD-APN team presentation/discussion to new graduates in the nurse residency program. This session, “Nurse as the Manager of Care,” incorporates and reinforces elements of the case studies, rounding, and teaching moment components of CCC tailored to meet the needs of new graduates.

Evaluating Cultural Transformation

In 2006, we conducted an open-ended physician satisfaction survey. We asked physicians to list three areas where the hospital was doing well and three where there were opportunities for improvement. One hundred and two surveys were complete. Fifty-five surveys listed nursing as one of the three positive areas at the hospital. No other answer in either a positive or negative area was as frequently listed.

On that same survey, physicians were asked two repeat questions from the 2004 redesign survey:

- Do you feel that nurses are knowledgeable of the patient’s condition and provide you with pertinent information when reporting changes in patient conditions to you?

- Do you feel nurses are timely in their follow through on written orders?

In contrast to the 25% on the original 2 years later, physicians felt that 81% of nurses are knowledgeable of their patients’ condition. They also answered that 86% of the time, nurses are timely in follow through on written orders, as opposed to 50% in 2004. (Figure 1)

![]()

A national physician satisfaction survey done by Data Management & Research, Inc, also in 2006, showed that 93% of physicians answered that they were either satisfied (73%) or very satisfied (20%) with nursing. Only 6% said they were dissatisfied, and 0% said they were very dissatisfied. This put the hospital at the 62nd percentile nationally, which was considered very positive by our consultants.

Many factors enter into measures of nursing satisfaction and turnover. The medical- surgical nursing division showed a decrease in nursing vacancy rates from 2004 (pre-CCC) to present and a continuous improvement in nursing staff perception of MD/RN interactions demonstrated in pre-session survey results.

In addition, quality measures also showed improvement after the redesign. For example, core measure bundle compliance scores for CHF, acute MI, community-acquired pneumonia, and SCIP (formerly SIP) bundles improved since inception of the CCC project. We felt that the CCC program has been complimentary to other strategies used to obtain these results. Since many of the aspects of bundle compliance involve specific MD orders, one can theorize that improved communication has led to easier conversations regarding specific orders needed related to the above categories.

Transforming the culture throughout the medical-surgical nursing division at Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital has been a journey. By cultivating the MD/RN relationship through the Communication, Collaboration and Critical Thinking = Quality Outcomes program and the assignment of unit-based APNs to each unit, along with a number of other initiatives, including rapid response teams, we have changed the very nature of how we do things. The scenario we described at the beginning of this article would look completely different in our practice today. In comparison to the first communication with the MD, the following alternative with the same patient situation illustrates how clear communication can contribute to a safer hospital experience and potentially better outcomes for this patient:

You are the same nurse on the same Friday evening shift. Before calling the MD, you organize data in the SBAR format advocated by JCAHO:

- S (situation): Mr. Z is a 285 pound male with a fractured ankle. His oxygen saturation level has dropped suddenly.

- B (background): He has a history of chronic obstructive lung disease and pulmonary embolism after a previous ankle fracture. Now he has a newly fractured ankle with normal preoperative labs and chest x-rays. The emergency room report states “the patient snores” when he is sleeping. Warfarin is on hold for surgery although his blood is borderline thinned.

- A (assessment): You think more data is needed to interpret his status. He has not had a blood gas done to check his pH, oxygen and carbon dioxide. He had a previous pulmonary embolism and we are now holding his warfarin with his INR at 1.9, which is not completely thinned. You are wondering if he might have a new blood clot or undiagnosed sleep apnea because of his body build and history of snoring.

- R (recommendation): You know there is a need to address pain but feel that with the oxygen problems and history of pulmonary embolism, the patient needs closer monitoring than can be given on the med-surg unit. Something has changed since he first got to the floor. Remember, our diagnosed sleep apnea patients go to critical care for monitoring after surgery when they are using narcotics for pain — this situation has some similarities (snoring, body habitus, narcotic use). You clearly convey the information above and your concerns to the attending physician.

Outcome after this communication:

- ICU transfer for closer monitoring.

- Work up for pulmonary embolism, blood gases, lung scan, and eventually an Inferior Vena cava filter to prevent pulmonary embolism while he is off warfarin for surgery.

- Pulmonary consult.

- Pain management consult.

- Successful surgery.

Conclusion

Critical thinking on the part of nursing and clear communication between physicians and nurses are paramount in promoting safe outcomes for patients. Creating a culture where nurses and physicians are comfortable with two-way communication regarding a patient’s condition and care needs requires careful planning, assembling of a team of key players, and persistence. Are nurses in your hospital able to put the critical pieces of information together in an organized fashion to present to the physician? Are your physicians receptive to nurses suggesting further interventions based on their assessment? The answer should be yes. If not, consider what needs to be done to begin a cultural transformation.

|

|

Mary Sue Dailey is a certified clinical nurse specialist for adult med-surg acute care at Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital, Downers Grove, Illinois. She has over 30 years nursing experience as a staff nurse, clinical faculty, case manager, and CNS. She is a Culture of Safety instructor and member of the CCC leadership team.

Barbara Loeb is a practicing internist at Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital with over 24 years of experience. She is board certified in internal medicine and geriatrics. Loeb has served in numerous leadership roles at the Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital and within the Advocate Health Care system including departmental chairman, member of the Corporate Quality Committee for Advocate Health Partners (PHO) and is currently the president elect of the medical staff. In 2005, she became focused on improving nursing quality and the MD/RN relationships. Loeb is the physician champion of the CCC Team and may be contacted at BLoeb5432@aol.com.

Cheryl Peterman is a certified clinical nurse specialist in adult health. She is the clinical specialist for telemetry at Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital. She has 5 years of nursing experience as a staff nurse, charge nurse, and CNS. She is a Culture of Safety instructor and member of the CCC leadership team.

References

Hanston, R.I, & Jackson, M. (2004). Clinical delegation skills: a handbook for professional practice. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Hanston, R. I. & Washburn, M. (1999). Individual and organizational Accountability for development of critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Administration, 29(11), 39-45.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Guidelines for communicating with physicians using the SBAR Process. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/SafetyGeneral/Tools/

SBARTechniqueforCommunicationASituationalBriefingModel.htm (accessed April 23, 2007)

Joint Commission. (2002) Joint Commission Perspectives on Patient Safety 2(9) 4-5

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations: 2006 Critical Access Hospital and Hospital National Patient Safety Goals. http://www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/

patient+safety/06_npsg/06_npsg_cah_hap.html (accessed April 23, 2006)

Kyser, S.P. (1996). Sharpening your critical thinking skills. Orthopaedic Nursing, 15(6), 66-76.

Larrabee, L., Janney, M., Ostrow, C., Withrow, M., Hobbs, G. Burant, C. (2003). Predicting registered nurse job satisfaction and intent to leave. Journal of Nursing, 33(5), 271-283.

Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. (2005). Disruptive behavior & clinical outcomes: Perceptions of nurses and physicians. American Journal of Nursing, 105(1), 54-64.

Schmalenberg, C., Kramer, M., King, C., et al. (2005). Excellence through evidence: Securing collegial/collaborative nurse-physician Relationships, part 1 Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(10), 450-458.