Biomarkers in Early Diagnosis of Sepsis: An Interview With Dr. François Ventura

By Michael Wong, JD

Dr. François Ventura is a specialist in anesthesiology, intensive care medicine, and emergency medicine at the University Hospitals of Geneva and at the Hirslanden Clinique des Grangettes (Geneva, Switzerland). He also collaborates part-time as the chief medical officer of Abionic, a Lausanne-based Swiss MedTech company specializing in the development of ultra-rapid in vitro diagnostic tests.

I first met him when he spoke on a case report he and his colleagues had published in the Journal of Surgical Case Reports. This report detailed a 62-year-old man who experienced complications of abdominal surgery with intra-abdominal infection, postoperative peritonitis, sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ failure requiring complex management and multiple surgical interventions.

Hearing about Dr. Ventura’s research on the use of serial pancreatic stone protein (PSP) to diagnose sepsis led our Sepsis Advisory Board to propose to the Global Sepsis Alliance that he be invited to speak at the 4th World Sepsis Congress on the topic “Current Research on Sepsis Biomarkers.” Biomarkers are biological molecules found in blood, other body fluids, or tissues that can help in diagnosis or treatment.

After the Congress, I had the opportunity of speaking to Dr. Ventura about his presentation.

Wong: Dr. Ventura, are biomarkers currently used to diagnose sepsis?

Dr. Francois Ventura: Sepsis occurs when the patient experiences a confluence of infection, inflammation, and organ dysfunction.

According to the latest Surviving Sepsis International Campaign Guidelines (October 2021), no biomarker is recommended for the diagnosis of infection, inflammation, and organ dysfunction:

- To determine infection, procalcitonin (PCT) is commonly used; however, studies find it has a number of limitations as a marker of bacterial infection, and it is therefore not recommended. Clinical evaluation is recommended as the best practice.

- To diagnose inflammation, a clinical systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score is recommended; however, studies show “almost all septic patients have SIRS, but not all SIRS patients are septic.”

- CRP is a traditional inflammation biomarker, but it isn’t specific enough for sepsis. Besides sepsis, you get inflammation due to infection, trauma, surgery, thrombosis, cancer, etc. So, CRP is not very useful for determining whether inflammation is due to sepsis.

- To diagnose organ dysfunction, the use of lactate is not recommended. Here again, it is clinical scores that are recommended (SOFA, NEWS, MEWS).

Wong: So, does current research hold much promise for the use of biomarkers?

Ventura: Unfortunately, the recommended clinical scores have poor specificity for infection, sepsis, and antibiotic administration. In Switzerland, almost all clinicians use biomarkers, and fewer than half use clinical scores. So, the use of biomarkers is very popular in my home country. The search for new specific and sensitive biomarkers of sepsis is therefore paramount.

In April, I conducted a PubMed search on “biomarker and sepsis.” It yielded nearly 12,200 results, of which 290 were from this year alone! A 2020 study lists 258 biomarkers. These include traditional ones, like leukocytes, CRP, PCT, and lactate; and new ones, like Il-6, presepsin, PSP, and MR-proADM. Nine new biomarkers are better than the traditional ones like CRP and PCT.

For infection, we have new technologies that identify bacteria in five hours—quicker than blood culture—and antibiogram in just five to six hours. However, these tests are too slow to assist in the decision to administer antibiotics, which must be done within one hour (< 45–60 minutes).

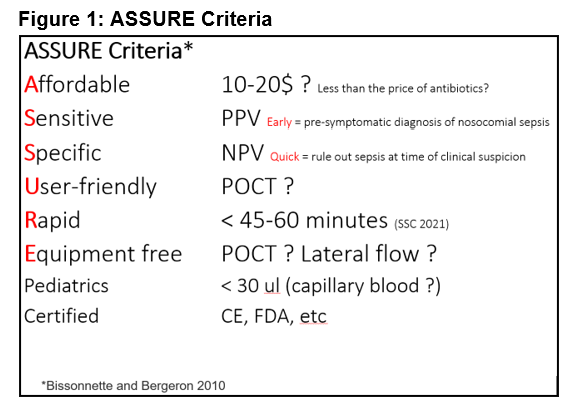

The explosion of research has led to criteria for selecting ideal biomarkers for sepsis. The ASSURE criteria require biomarkers to be simultaneously Affordable (less than the price of antibiotics), Sensitive (for early diagnosis), Specific (for quick diagnosis), User-friendly, Rapid (< 45–60 minutes), and Equipment-free or at the bedside. Obviously, the biomarker must be certified (FDA, CE, etc.). [Editor’s note: See Figure 1.]

Wong: Speed of diagnosis is certainly critical, but what’s the difference between early and quick?

Ventura: Early means “before symptoms.” We need biomarkers that detect sepsis in hospitalized patients at risk of infection and nosocomial sepsis before a clinician even suspects it. For early diagnosis, the biomarker should be sensitive, that is, have high positive predictive value. This is referred to as pre-symptomatic diagnosis of nosocomial sepsis.

Quick relates to “at time of clinical suspicion.” If clinicians suspect sepsis, they should be able to confirm or rule it out as quickly as possible (< 45–60 minutes). In sepsis, speed is critical—starting antibiotics quickly can be the difference between life and death. Simultaneously, we must avoid giving antibiotics unnecessarily: Antibiotic resistance is a major problem. So, biomarkers for quick diagnosis must have high specificity, that is, high negative predictive value.

Wong: Is the case report of using the PSP biomarker that you discussed with me last year a good example of using an ASSURE biomarker?

Ventura: PSP is produced in response to infection and sepsis. Its level in the blood increases progressively in patients with infection, sepsis, and septic shock. The test is done in seven minutes at the bedside, using new nanofluidic biosensors. It is very good for early (pre-symptomatic) diagnosis of nosocomial sepsis because its level increases already three to five days before symptoms of nosocomial sepsis appear. PSP combined with CRP has good specificity and negative predictive value at the time of clinical suspicion of sepsis, allowing a quick (<10 minutes) decision on whether to give antibiotics.

There have been more than 600 peer-reviewed studies on PSP. Forty-six of these studies are specific to sepsis, including a prospective multicentric study and a meta-analysis. So, yes, the PSP does meet the ASSURE criteria. PSP is already certified in Switzerland, in Europe, in Australia, and hopefully soon in the U.S.

Wong: Where can I read more about biomarkers for sepsis?

Ventura: I recommend the bibliography to an article titled “Sepsis Diagnosis: Clinical Signs, Scores, and Biomarkers” that my colleagues and I wrote for ICU Management & Practice.

For a quick overview, please watch my presentation at the 4th World Sepsis Congress. I understand the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety is providing continuing medical education credits for watching it.

Wong: Thank you so much for answering my questions, Dr. Ventura. I encourage everyone to watch your Congress presentation and all clinicians to watch and get rewarded credits.

Ventura: You are most welcome!

Michael Wong, JD, is executive director of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety.