Barcode Technology for Positive Patient Identification Prior to Transfusion

July/August 2011

Barcode Technology for Positive Patient Identification Prior to Transfusion

Renewed initiative engages nurses and achieves 100% compliance.

In today’s increasingly complex, highly demanding clinical environment, introducing a new technology is challenging under the best of circumstances. What if, right when roll-out is going well, an unrelated connectivity interruption leads nurses to conclude “this doesn’t work”? You need to get your initiative back on track—especially when it relates to improving the safety of a critically important patient-care process. How do you meet your end-users’ needs, protect your hospital’s considerable investment, get the positive results leadership expects, and, most importantly, help improve patient safety and quality of care?

Saint Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia, (Saint Joseph’s) faced exactly this challenge, just days after go-live with a positive patient identification (PPID) software platform that had been carefully evaluated and selected to help improve blood transfusion safety. After the software platform and mobile barcode devices had been successfully installed throughout the hospital, modifications to the hospital’s wireless network caused significant connectivity issues for more than 10 weeks. Although not device-related, nurses perceived this problem as a product failure and were reluctant to change from their manual method of transfusion administration.

Resolving the network connectivity issues did not resolve nurses’ negative perception of the new technology. Initial data analysis showed that 16 months post-implementation, the compliance rate with barcode transfusion verification use was only 21%, rose briefly to 40%, and dropped back down.

|

Founded by the Sisters of Mercy in 1880, Saint Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta is now a 410-bed, acute-care hospital recognized as one of the leading specialty-referral hospitals in the Southeast. Saint Joseph’s is the region’s premier provider of cardiac, vascular, oncology, and orthopedic services and home to the most comprehensive minimally-invasive robotic surgery program in the world. Saint Joseph’s is one of the 50 top hospitals listed by US News and World Report and has received Magnet Recognition for Nursing Excellence. |

Saint Joseph’s is known for its longstanding commitment to safety, and this was not acceptable. After seeing the data, a small, multidisciplinary team of laboratory staff, nursing educators and managers, and patient safety and quality personnel took responsibility to dramatically improve compliance rates.

In this article, the multidisciplinary approaches that successfully re-launched the barcode transfusion verification initiative and the results achieved in improving compliance are described. The need to improve transfusion safety, technology selection and implementation, continuing enhancements, and extension of the positive patient identification software platform to specimen collection and medication administration are briefly reviewed.

Transfusion Safety at the Point of Care

In 2006 in the United States more than 30 million blood products were transfused. That year 72,000 transfusion-related adverse reactions were reported, including 73 deaths (Whitaker et al., 2008). A leading cause of transfusion-related death is hemolytic transfusion reaction, whereby transfusing a patient with ABO-incompatible blood triggers an immune response that destroys the transfused red blood cells (FDA, 2008). Although rarely fatal, a hemolytic transfusion reaction often significantly increases morbidity and length of stay.

Patient misidentification is the leading cause of incompatible blood transfusion (Linden et al, 2000; Stainsby et al, 2008; Stainsby, SHOT, 2008). To improve the accuracy of patient identification, the first National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG.01) was “Use at least two identifiers when providing care, treatment and services” (The Joint Commission, 2009). PPID barcode technology helps ensure that the right blood product gets to the right patient, thus avoiding the transfusion of ABO-incompatible blood. This meets NPSG.01.03.01, “Eliminate transfusion errors related to patient misidentification.”

Barcode-based transfusion verification systems have been shown to be 15 to 20 times safer than most hospital transfusion systems used in the United States (Askeland et al, 2009). Barcode systems that use existing blood product labeling and patient armbands are considered ‘‘the obvious first choice for machine-readable technology to prevent transfusion errors” (Dzik, 2005, p478).

Saint Joseph’s Barcode Safety Initiative

Saint Joseph’s began its barcode initiative not in reaction to an adverse event but as a positive response to The Joint Commission’s recommendations that hospitals improve the accuracy of patient identification to reduce the risk of errors in patient identification, particularly with regard to blood-product transfusions.

In October 2004 the laboratory information services (LIS) manager and was charged with implementing PPID barcode technology that could support specimen collection verification and transfusion verification, and also be expanded to support medication administration verification. A major upgrade to the LIS delayed the implementation of specimen collection verification, and the focus shifted to implementing a barcode technology with transfusion verification as the first application.

Saint Joseph’s averages more than 1200 transfusions per month for blood, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma. Implementation of a barcode system to help ensure positive patient and blood product identification was essential to optimize patient safety and quality of care.

To help ensure successful implementation, the evaluation and selection of a new technology involved as many front-line clinicians as possible, including nursing, pharmacy, information technology (IT), and laboratory personnel. Key factors in the selection of barcode transfusion verification technology were that it be intuitive and easy to use, complement and streamline clinical workflow processes, be easily customizable to support the clinical end users’ workflow, support other PPID products to verify and label laboratory specimens, verify medication administration, and be able to work with any other information system. The vendor’s willingness to work with hospital staff to best meet the end-users’ needs was also significant.

Acquisition of a transfusion verification system was completed in June 2005. The first steps prior to installation were to optimize workflow processes for nursing and the blood bank and to establish wireless connectivity to exchange information between the transfusion verification system and the LIS. The system was further tested by LIS and blood bank personnel. Nurse educators also had an opportunity to work with the new technology. For implementation, the vendor provided a detailed plan that was then customized to Saint Joseph’s. The resulting go-live was one of the easiest the staff had experienced. Installation continued throughout the hospital, with all units live in August 2007. Then the wireless network crashed.

Unexpected Challenge

The wireless connectivity issues were not resolved for 2-1/2 months. After wireless connectivity was restored, the nurses’ negative perception remained, and with the exception of those in outpatient oncology, they were slow to resume using the transfusion verification device. Before the laboratory personnel could concentrate on resolving this issue, they had to focus on upgrading the laboratory information system, including installing new hardware, which took about 2 years. That was followed by implementing the barcode system for specimen collection, which involved a different group of end-users: IV therapy and phlebotomists. Once that was completed in February 2009, the LIS staff could once again focus on resolving the compliance issues around transfusion verification. The challenge was to successfully re-launch the initiative after an extensive delay.

Achieving Compliance with Transfusion Verification Use

A cross-functional taskforce comprising representatives from nursing, laboratory, and patient safety evaluated the possible barriers to use, planned how to address end-users’ needs and concerns, and developed new approaches for education/re-education. The team also strongly supported one another as the initiative was re-launched in March 2009. Two related efforts combined to recharge the transfusion verification initiative and dramatically improve compliance rates: the immediate responsiveness by LIS staff to nurses’ questions or complaints, and a high-level initiative to be ever ready to meet regulatory requirements or be audited by The Joint Commission. Technology enhancements also improved the device’s ease of use, and compliance tracking and feedback were critical to achieving the desired results.

Communication between nursing and the LIS staff was crucial. The LIS manager reached out to nurses by encouraging them to call her if they encountered any difficulties with the transfusion verification device. Laboratory personnel were available to answer questions and provide bedside and telephone support on-demand. For example, one morning when the hand-held devices were not working, a nurse called the LIS manager, who immediately went to the nursing unit. She identified that nurses on the earlier shift had not docked the hand-held devices correctly to charge them overnight. As a result, the devices did not work in the morning. The cumulative impact of such immediate response helped to change perceptions and increase use of the transfusion verification device.

A clinical specialist at the Center for Nursing Excellence conducted additional training and made sure the nurse educators on the units remained vigilant in identifying a need for individual attention. Change-adverse individuals were given extensive one-on-one training and additional reading material to help them move past any internal reluctance they were experiencing.

The Joint Commission Readiness

The manager of regulatory services, who was a former surveyor for The Joint Commission, was charged by senior leadership with ensuring that all regulatory standards were being followed and that Saint Joseph’s was “ever ready” to be audited. Executive support was very high. The Core Regulatory Team included managers and directors from nursing, pharmacy, laboratory, patient care, health information, and many other departments. The chief medical officer took ownership for the chapter on leadership, went to the board and the chief executive officer (CEO), and informed them of all the efforts to ensure constant readiness for an audit by The Joint Commission. The manager of regulatory services brought a large group of people together and gave the responsibility to them and their teams. Empowering the staff, the managers, and the clinicians was essential, because it is at the bedside that the National Patient Safety Goals are achieved.

Sixteen nurses in a career development program were assigned to do mock surveys, which included questions about transfusion verification use. If someone was not doing something correctly, they taught that person the right way, right then. They showed the nurses what the transfusion technology does and explained that is important not because of Joint Commission requirements but because it is the right thing to do for a patient. In approximately 3 months, word of mouth spread the knowledge and understanding from one nurse to another, as they saw what needed to be done and understood why.

The LIS manager also became part of the orientation program for newly hired nurses. Since it was not possible to train all the nurses right away, nurse educators started with new-hire nurse orientation and then went to the floors to re-educate the current staff.

The team also created laminated posters with transfusion verification instructions, which were displayed in every unit, as well as pocket-sized instruction cards for the individual nurses. Transfusion verification use was added to the annual skills lab for nurses. The team also demonstrated the transfusion verification system for the CEO and vice presidents of the hospital.

Technology Enhancements

|

|

To prevent the workaround of nurses’ scanning the barcode in the chart and not on the wristband, non-armband patient labels were configured using a check digit, making it unreadable on the handheld device.

Saint Joseph’s nurses also worked with the vendor to develop a new feature that would support transfusion verification and PPID, yet allow for rapid infusions of blood. The new rapid infusion mode allows for administration of blood in an emergent situation while still positively identifying the patient. After this new mode was added to the system, a CVICU patient needed 41 Units of blood, and 38 Units were transfused using the rapid infusion mode. Without this enhancement, nurses in an emergent situation likely would have bypassed the barcode transfusion verification system, potentially increasing the risk of an error.

Compliance Tracking and Feedback

The LIS staff tracked overall transfusion verification compliance rates and reported these back to nursing units; however, reporting overall rates had no impact. They then reported compliance rates by individual nursing unit, for example, “More than 250 blood products were released to this unit; 20 were transfused using the device.” Reports separated weekday and weekend usage and identified individual nurses who required additional education.

The team never indulged in finger-pointing and always gave a nurse the benefit of the doubt as to why the transfusion verification system might not have been used. Nurse educators posted the statistics in each unit, often adding notes of encouragement. Unit-specific reporting appealed to nurses’ professional pride and peer pressure. If they saw poor results, the nurse managers would request that the nursing educator come to retrain their staff. As adult learners, once nurses understand the reason for doing something, they will do it. “Because The Joint Commission says so” is not good enough.

Once success was seen in the critical care areas, the team focused on the acute care units, using the same one-on-one approach to overcome any remaining reluctance on the part of change-adverse individuals.

Results

During the initial use of the transfusion verification system, an auditor from The Joint Commission observed a nurse on a non-pilot unit using a manual process for blood transfusion administration and then a pilot-unit nurse using the new barcode technology to demonstrate PPID for transfusion verification. The auditor reported to the executive team that the new transfusion verification technology had prevented Saint Joseph’s from receiving a Requirement for Improvement (RFI) and made positive remarks about the hospital’s use of the new technology.

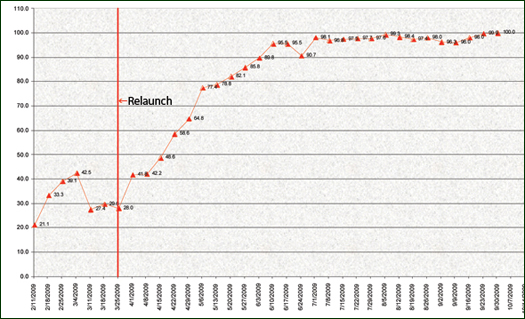

By the end of June 2009, 3 months after the re-launch of the transfusion verification initiative, hospital-wide compliance was more than 90%, and weekday and weekend compliance rates converged. The compliance rate stayed in the high 90s and in August was more than 99% (Figure 1). Since then nurses have maintained close to 100% compliance to date.

Figure 1. Transfusion Verification Overall Compliance Rates

Nurses throughout the hospital report anecdotally that use of the barcode transfusion verification system has increased their satisfaction, because they are confident that the technology is making the process safer.

Clinical staff voted to give the in-house Patient Safety and Quality Award to this joint nursing-LIS initiative. Receiving the People’s Choice Award from the nursing staff was especially meaningful. Out of 25 different projects, the nurses voted transfusion verification as the best, a strong indication of their support for and satisfaction with the system.

The new transfusion verification system was reported positively in the local press and media, supporting Saint Joseph’s marketing efforts and strengthening consumer confidence in the organization’s commitment to safety and quality care.

Discussion

The nurses at Saint Joseph’s follow a shared governance model as a means of providing quality care. They readily embraced the new technology once they recognized the benefits to the patient. The hospital’s goal is not simply to meet The Joint Commission standards but to exceed them. Continued use of the barcode transfusion verification system helps ensure that safe and quality care is provided to all patients through the use of best practices.

In late 2010, Saint Joseph’s implemented the software’s medication administration module. The software platform provides a single database and a common user experience for transfusion and specimen collection verification, and medication administration.

Conclusions

In today’s increasingly complex clinical environment, the use of patient safety technology is imperative to help clinicians avert medical and medication errors. Saint Joseph’s has successfully implemented barcode technology that provides positive identification for blood transfusion, as well as for specimen collection and medication administration. Use of this technology helps Saint Joseph’s meet the standards of The Joint Commission and, most importantly, ensure that the right patient receives the right blood product or medication at the right time.

Critical success factors in achieving near 100% compliance with barcode transfusion verification technology use included the culture of safety at Saint Joseph’s; multidisciplinary collaboration; proven, easy-to-use barcode technology; a high-level commitment to being ever ready for The Joint Commission; a strong vendor partnership; responsiveness to end-users’ needs; and the understanding that use of the barcode technology was the right thing to do for the patient.

The clinical experience at Saint Joseph’s shows that even when a technology initiative stalls and compliance falls to unacceptable rates, a coordinated team effort can successfully engage the nurses, demonstrate how the technology benefits their patients, and achieve nursing’s full compliance in using the new technology to help ensure patient safety and provide the highest-quality care.

Appreciation

The authors express their appreciation to Sally Graver, senior medical writer for CareFusion, for her assistance with manuscript development.

Eileen Stone is the laboratory information systems manager at Saint Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta. She is a graduate of the College of Staten Island, Richmond, New York, where she earned a bachelor of science degree in medical technology, and is an ASCP-registered laboratory technologist. Stone earned a master of science degree in medical microbiology from Long Island University, Brooklyn, New York, and holds certification as a Usability Engineer from the Georgia Institute of Technology. She has 18 years experience as a microbiology supervisor, 10 years as a laboratory systems designer and 10 years in LIS management. Stone may be contacted at estone@sjha.org.

Patty Sherwood Keenan is a healthcare consultant specializing in hospital administration and preparation for state, Medicare, and Joint Commission surveys. Keenan was previously employed by The Joint Commission where she served as a nurse surveyor for more than 7 years. She has also served as a director of quality management at both Kindred and Tenet Healthcare Systems and corporate director for Regency Hospital Company. At the time this article was written, Keenan was the regulatory services manager at Saint Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta. Keenan is a graduate of Georgia State University in Atlanta, where she earned a bachelor of science degree in nursing. She earned her master of science in nursing administration degree from The Medical University of South Carolina. Keenan currently teaches the Certified Professional in Healthcare Quality review course for the National Association for Healthcare Quality (NAHQ) and may be contacted at keenanp158@bellsouth.net.