Applying Lessons Learned to Accelerated Adoption of BCMA

March / April 2012

![]()

Applying Lessons Learned to Accelerated Adoption of BCMA

| |

|

|

|

When JFK Medical Center in central New Jersey went live with barcoded medication administration (BCMA) in 2009, it took 12 months to reach and maintain a 97% scanning rate. The organization did not intend to stop after just three patient care units, but priorities changed, and the rollout was suspended. In 2011 when it came time to resume deployment house-wide, we had the benefit of our own experience (McNulty, Donnelly & Iorio, 2009) as well as industry knowledge about how nursing workarounds and technology failures could undermine the patient safety benefits of a BCMA system (Koppel, Wetterneck, Telles & Karsh, 2008). In this article, we present the lessons learned during initial BCMA implementation and describe how they were applied to the subsequent house-wide rollout.

Then and Now

For the 2009 pilot, we assembled a multidisciplinary team including pharmacy, IT, and nursing to systematically identify and address educational, technological, and process-oriented issues. These ranged from engaging frontline nurses in device selection, screen design, and navigation, to installing additional wireless access points, to engaging process engineers to map the workflow and help eliminate unnecessary footsteps. During the pilot, we established a process of monitoring scanning percentages, enabling us to quickly identify and address the issues that resulted in workarounds to the scanning process.

In preparation for house-wide rollout, the multidisciplinary stakeholders convened to identify lessons learned from the first three units and create a new plan. Armed with a BCMA scanning compliance report and medication safety reports (the original “incident reports” were renamed “safety reports” because they are used to build a safe system) along with feedback from pharmacists and nurses directly involved in the workflow, we developed far more effective approaches and were able to reach 97% scanning rate in just 3 months, across five units. Of the many lessons we were able to leverage, here are the most important.

Be guided by the data.

BCMA is a high-profile initiative for JFK Medical Center. Monthly reports regarding barcode compliance are circulated to all levels of the organization, including the Board of Directors. Especially during the rollout, this visibility kept the focus on finding and addressing issues. The data was organized and analyzed to guide process improvement plans. The team reviewed report details and discussed root causes and solutions. Understanding the reason for workarounds helped the team generate effective improvements and process changes that work for all the stakeholders.

Reports helped identify system errors that may or may not relate to BCMA and guide further improvement. Daily barcode compliance reports captured all overrides by unit, by nurse. This data provided information that led to improvements in technology, processes, and education. For example, we found a variety of scanning issues and determined that maintaining scannable barcodes required daily maintenance by a pharmacist. As a result, we have dedicated a pharmacist informaticist to design the pharmacy process, validate all barcodes, maintain scanners, educate other pharmacists, review scanning reports, identify trends, collect medications that don’t scan from the nursing units, and be the process expert who works with nurses when scanning issues arise. For example, after noting that oncology nurses had a low scanning rate, we discovered that they wanted chemotherapy orders to remain visible for some time even after administration. To accommodate their workflow, pharmacists now maintain one-time chemotherapy orders on the electronic medication administration record (eMAR) for 10 hours.

Heed the source of truth.

Before launching the house-wide rollout, the multidisciplinary team reviewed the preceding year’s medication error reports across all live units (June 2010 to June 2011). Out of 49 total errors, we determined that nearly a quarter (11, or 23%) could not have been prevented by correct use of BMCA. However, many of those errors could have been prevented by confirming the eMAR with the source of truth—the original provider-generated order in the patient’s medical record—or by a daily chart check by nursing, a common practice where the night nurses compare the original medication orders to the patient’s eMAR.

|

Critical Success Factors for BCMA

|

Barcode scanning is designed to ensure that clinicians follow the “five rights” of medication administration, not cede responsibility to the technology. Any time the clinician scans a new medication or a change in medication, the order must be validated with the original provider-generated order to confirm that they match. Nurses must be taught that this step is essential to catch a transcription error before it reaches the patient (van Onzenoort et al., 2008). The confirmation step ensures that the medication order has been reviewed by both a pharmacist and a nurse prior to administration. Without computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE), the BCMA process requires this confirmation step because transcription by the pharmacist is still vulnerable to human error. Our system now requires nurses to click to confirm that the order was verified by nursing before proceeding, but even this action can become rote. To address this, nursing redesigned the process for 24-hour chart checks and emphasized the need for the confirmation step during education. To help frontline nurses learn from these errors, nurse managers are encouraged to share stories of medication errors that would have been prevented by carrying out this step.

In addition, when administering any medication, new or not, the nurse must visually check the computer screen for the medication name and the dose. For example, when preparing insulin, the nurse must read the order on the screen and change the units/volume in the dispensing field.

Focus on nursing-pharmacy relationships.

To support BCMA, several years ago JFK also automated its pharmacy with a robotics dispensing system, pharmacy order entry system, and unit-dose barcode packaging solution. While pharmacy automation is highly effective, until we deploy CPOE and achieve high adoption, pharmacy transcription errors remain a concern.

Nurse confirmation of the pharmacist’s transcription is a new workflow and mindset that requires effective change management to ensure it takes hold. There must be ongoing efforts to build alliances between nursing and pharmacy. The multidisciplinary planning team sets the tone and looks for opportunities to build relationships between individual staff members. To promote interaction, nurses and pharmacists were educated jointly. In these sessions, the nurses learned the pharmacists’ processes and pain points and vice versa. In addition, every other week, a nurse-pharmacy committee convenes to review the safety reports together. These experiences foster collaboration and improve communication. When each discipline understands the other’s workflow, process issues can be resolved more quickly or avoided completely.

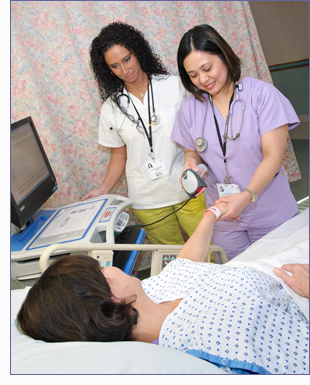

Courtesy of JFK Medical Center

Put it into context.

BCMA introduces a radically new workflow to frontline nurses. Gooder (2011) reported that it may cause negative attitudes toward medication administration and suggests that effective implementation requires an understanding of system impact on nursing workflow. Based on interviews with experienced nurses from our pilot units, for the house-wide rollout we understood the value of introducing BCMA in the context of the nursing process: conducting a patient needs assessment, determining priorities, administering medications, evaluating the patient, and scheduling interventions to meet their needs. BCMA workflow changes were presented in the context of delivering safer patient care. Barcode scanning was described as tool for enhancing the safety of medication administration, not a substitute for nursing judgment and critical thinking.

We also relied heavily on experienced nurses from our pilot units for both training and support. Certainly delaying a house-wide rollout is not ideal, but if you do have staff nurses who are familiar with BCMA and your hospital’s pharmacy and nursing processes, by all means leverage them. This approach enhanced rapid adoption and enabled us to reduce classroom instruction from 8 hours to 4 hours.

Following our house-wide go-live, nurses on every unit expressed the value of learning from another nurse who had first-hand knowledge of the BCMA system and the hospital processes. The nurse rounders supporting the go-live were the clinical and hands-on experts for their peers. For example, insulin and cardiac medications often require additional steps for patient assessment and documentation. Relying on nurses with practical knowledge to provide the know-how to change medication schedules, adjust workflow, incorporate documentation, and troubleshoot on-the-spot during the first few weeks of go-live helped minimize delays in medication administration. Their expertise produced a calming influence and decreased the stress associated with taking care of patients while learning a new system.

Culture of safety is the foundation.

“Perfect safety… doesn’t mean eliminating all mistakes. It means structuring a system that expects and safely deals with mistakes. That’s the essence of a high reliability organization” (Nance, 2009). This concept is put into practice in the two-step process for validating the transcribed order with the original provider-generated order: the nurse confirmation and the daily chart check. The assumption is that there is a pharmacy transcription error. The two- step confirmation can prevent the error from reaching the patient.

Ethnographic observations by Patterson, Cook and Render (2002) found side effects of BCMA that could have a negative impact on nursing. They recommend that organizations monitor the process for possible adverse effects and modify design and policies accordingly. The multidisciplinary review of medication safety reports is a forum to monitor the process and redesign systems accordingly.

|

Acknowledgement The authors would like to acknowledge the following clinicians for contributing to this article: Rhoda Eusebio, RN, BSN |

It may be tempting to accept that there will always be a certain amount of human error. A recent Institute of Medicine report concluded that improving the safety of health IT-assisted care begins with viewing health information technology as part of larger sociotechnical system, in which all stakeholders must work together to improve patient safety (Institute of Medicine, 2012). In other words, the culture you build is the foundation for a safe system. We built relationships by educating nurses and pharmacists together and assigning a pharmacist to be a resource to the nurses to troubleshoot issues. To be sure, this is an ongoing process. We continue to look for opportunities to foster those collegial relationships.

Leadership is key.

Change is risky, highly political, messy, personal, disruptive, and complex (Kaminski, n.d.). Successful change requires leadership to shape the culture. In our organization, the vice president for patient safety, a physician, convenes the multidisciplinary group regularly to review all the medication safety reports and look for common themes. The tenor of this meeting is mutually respectful and constructive. Participants include pharmacists who enter orders, frontline nurses, a pharmacist informaticist, IT staff, and managers. The perspective of those who use the system is essential to understanding why errors have occurred. Many workarounds, and often the reasons for them, can only be identified by the people who are directly involved.

In reviewing all safety reports, this team takes a broad view of the medication administration process and continually identifies new, unexpected issues. Hospitals are complex, and it is impossible to predict how changes in other areas may impact medication administration. The key is keep a dedicated team focused on uncovering system issues and solving problems across disciplines.

Robert Bayly is vice president for patient safety at JFK Health System, which includes JFK Medical Center, a 499-bed acute-care hospital in Edison, New Jersey.

Susan Imhoff is physician adoption leader and manager, Patient Safety Institute, JFK Health System. She may be reached at Simhoff@solarishs.org.