Addressing and Extending Psychosocial Care and Support to Patients and HCWs During COVID-19

By Tanuja Nair, Kayla Carissa Wong, Lily Ang Gek Lan, Koh Shuping, and Pearlyn Lee Peiling

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) first made its appearance on the world stage in China back in December 2019. Within a span of just five months, the virus spread and held the world hostage. Countries across the globe raced against time to try to make sense of this pandemic, and many countries were forced to implement measures such as quarantines, curfews, and lockdowns in an effort to curb the exponential transmission of the virus. By summer, there were more than 8.8 million confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide and more than 465,000 deaths. Within the island city of Singapore alone, home to over 5.8 million people, there have been over 42,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases with 26 deaths (World Health Organization, 2020a).

Following the lead of many countries, on April 7, the Singapore government placed the country under a two-month modified lockdown state known as a circuit breaker. Citizens and residents alike were asked to stay at home, and a cordon sanitaire was applied where only essential services were allowed to function.

Implications for children in isolation

While the total number of children infected by the disease in Singapore was small, there was still a need to look out for them. Children are at a higher risk for mental health issues as they often do not fully understand emergency situations, are unable to communicate their emotions effectively, and have limited coping strategies (Imran et al., 2020).

In the authors’ hospital of practice, patients who required isolation at the hospital had to adhere to strict infection control protocols, and some did not have a readily available caregiver who could room with them. While provisions were made for these patients to receive some of their essential belongings from home such as their gadgets, phones, and toys, many were unable to access them owing to caregiver challenges, giving rise to feelings of isolation and displacement. This finding was corroborated in a study by Alvarez et al. (2020), where patients and caregivers in isolation shared that navigating and understanding isolation protocols represented one of their primary struggles.

According to Imran et al. (2020), children isolated due to suspicion of COVID-19 have higher risks of developing and maintaining mental health disorders for months and even years. Reasons cited in his study for such a consequence included children being separated from caregivers owing to hospitalization stays, fear of the disease, and social isolation. There has been extensive research that illustrates the devastating effects of anxiety-ridden childhood experiences such as hospitalization and isolation on a child’s physical and emotional development (Lerwick, 2016). This sentiment was also shared by Fegert et al. (2020). In that study, which was conducted in Central North America after epidemics such as H1N1 and SARS, the psychological impact of quarantine was observed to include depression, fear, and anxiety. That study illustrated how a worrying 30% of isolated or quarantined children met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder.

To mitigate similar dire consequences and promote overall coping, the authors of this article began to plan for a coping package, which is the minimal level of effective care that should be provided during such crucial times (Burns-Nader & Hernandez-Reif, 2016). However, given the need to change operation modes owing to the nature of the pandemic, treatment and care plans would have to be fluid and innovative (Fegert et al., 2020). Adopting best practice recommendations by the World Health Organization (2020b), the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action (2020), and Osofsky & Osofsky (2020), the authors endeavored to ensure that the pediatric patients (and their families) in hospital isolation still had a daily routine filled with familiar activities.

Implications for healthcare

In the healthcare sector, visitor restrictions were implemented to prevent the further transmission of the coronavirus. Within the hospitals, only essential individual patient services continued, with many outpatient and therapeutic group sessions being put on hold. The authors’ hospital of practice—one of the primary pediatric hospitals in Singapore—experienced a similar impact across its patient population.

Patients admitted to the wards as either confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases were kept in isolation, and only a specific team of healthcare workers (HCW) were assigned to work with them. HCWs themselves had to battle fatigue and stress while ensuring that their patient care and support were upheld to the highest standards and never compromised. A Singaporean HCW study by Tan et al. (2020) observed that 10.8% of medical HCWs and a resounding 20.7% of non-medical HCWs reported feeling anxious during this pandemic. Noting these distressing figures, we also recognized the need to extend support to our fellow colleagues.

Developing the CaRES initiative

In the authors’ institute of practice, a multimodality team made up of child life therapists, art therapists, and music therapists are typically on hand to provide psychosocial and functional support to pediatric patients. Known as CHAMPs (Child Life, Art, and Music Therapy Programs), this team looks at improving our patients’ hospital experience. The challenge that arose for the team during this outbreak was the inability to conduct individual or therapeutic group sessions for patients in isolation. The usual mode of support and engagement had to be quickly modified so that CHAMPs could stay connected and provide support to these vulnerable patients, which as of May 31 stood at over 800 confirmed and suspected cases.

The CHAMPs CaRES (Compassionate and Responsive Engagement Support) initiative was developed within a span of days, in which the team pulled together support, education, and engagement resources for hospital patients. The variety in resources was based on the understanding of purposeful and familiar engagement to promote emotional and behavioral self-regulation in children, as advocated for by Skinner & Edge (1998). Resources and programs were developed to help mitigate patients’ possible sense of isolation and anxiety—similar to a call that was put forth by the United Nations Sustainable Development Group (2020). These resources additionally aimed to engage children through familiar and enjoyable activities such as play so that their overall sense of health and well-being was not vastly compromised owing to their hospital stay—a sentiment shared by Shaw & DeMaso (2006).

Specifics of the CHAMPs CaRES initiative

To effectively address the varied needs of patients, a variety of developmentally appropriate resources were created. They included:

- Curating weekly age-appropriate care packs for hospitalized children in isolation to ensure that they had meaningful and familiar activities to help them cope emotionally (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Weekly Age-Appropriate Care Packs for Hospitalized Children in Isolation

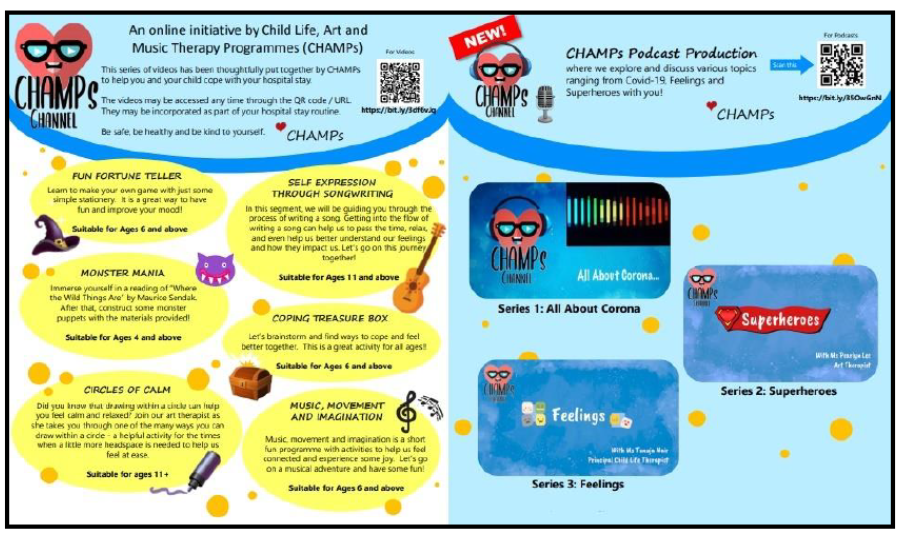

- Creating a six-part video with an accompanying video activity kit for hospitalized children in isolation and a three-part children’s podcast series for hospitalized children and members of the public. These videos and podcast episodes focused on meaningful and therapeutic themes of effective coping and resilience building to empower the children and members of the public with psychosocial and emotional well-being tools (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Six-Part Activity Video Kit and Three-Part Podcast Series

Additionally, the team extended psychosocial support to the HCWs and members of the public affected by the outbreak. This included:

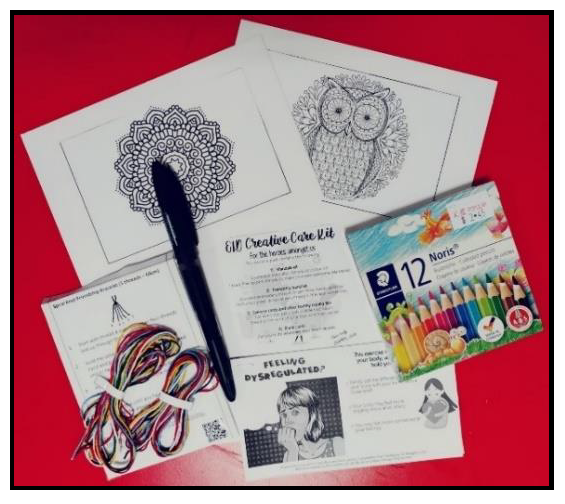

- Curating staff coping kits to encourage positive coping during stressful times, comprising simple coping strategies such as breathing and relaxation techniques and diversion activities such as friendship band making and mindful coloring activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Staff Coping Kit

- Curating staff welfare kits comprising sweet treats and snacks with an accompanying message of encouragement and thanks to let fellow colleagues know that their frontline efforts were appreciated and that they were being thought of during this pandemic (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Staff Welfare Kits

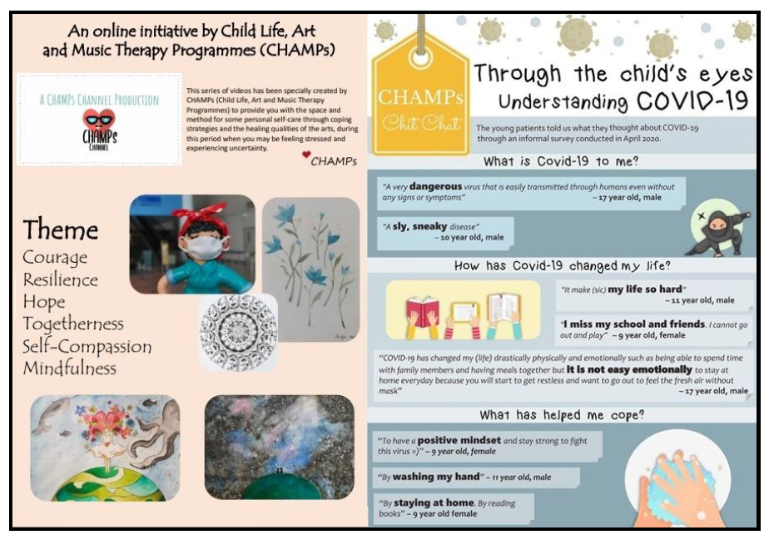

- Creating a six-part wellness video series and a newsletter for staff and members of the public around themes of strength, hope, and psychoeducation to further contribute to their overall emotional healthcare and wellness (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Six-Part Wellness Video Series and Newsletter

The patient care packs, activity kits, and staff welfare kits were distributed across five wards, while the videos, podcast series, and other print resources were uploaded onto relevant hospital e-platforms for easy access and wider outreach.

Impact and Outreach

As of June 15, nearly 500 care and activity kits were distributed across the wards that served as temporary homes to pediatric patients admitted as confirmed and suspected COVID-19 cases. The activity and podcast series, which were hosted on the hospital’s YouTube and Facebook platforms, garnered nearly 3,000 views, while the wellness video series garnered nearly 5,000 views. Staff who received the coping kits said they found them useful as a form of therapeutic diversion; they also said the notes and treats were well appreciated and reminded them that they were not alone in their frontline battles.

Discussion

The idea behind CHAMPs CaRES was to ensure that the unique needs of hospitalized children (suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients) and their caregivers were still attended to despite their isolation predicament. Ensuring that this vulnerable patient population continued having access to resources as a form of diversion and coping was imperative in ensuring that their overall psychosocial needs were met. Alvarez et al.’s (2020) study seconded this when the interviews conducted in that study revealed how children and parents found activities to be helpful as a means of coping with isolated hospital stays.

An interesting finding during this period was the crucial role technology played in alleviating some of the negative impacts of isolation. The team received numerous requests to facilitate the loan of electronic gadgets such as television sets, handheld devices, etc. While monitoring screen time and ensuring children do not get obsessed with their gadgets and subsequently develop negative behaviors are valid concerns (Guerrero et al., 2019), there is also growing research to support the benefits of technology. In this day and age, technology plays a key role in many of our lives. Not only is it a source of information, but technology also provides a platform to facilitate virtual connection and interaction—essential components sought after by many who are in isolation.

In one of the podcast episodes by CHAMPs, staff interviewed children and asked them to share encouraging messages of hope and support for friends or peers who might be in the hospital or otherwise facing a trying time. The children agreed, and through technology, these inspiring messages of positivity and encouragement were broadcast to their vulnerable peers whom they could not meet in person. Such virtual connection and support instilled a semblance of togetherness despite the physical constraints.

Extending similar support to HCWs and members of the public was equally beneficial in fostering unity and strength during the pandemic. HCWs are constantly on the front lines, and being first responders, they face many possible grim scenarios. The importance of providing support to promote their mental and emotional wellness should never be underestimated. Kpassagou & Soedje (2017) observed this in their study where mentally strong and supported HCWs reported having better mental clarity to make important clinical decisions.

The CaRES initiative was cost efficient, and the resources developed and curated were made available to various populations within the healthcare system and beyond. The findings from this initiative suggest the need to continue to develop resources and skill sets to better address the ever-changing needs of patients, families, HCWs, and members of the public.

Conclusion

The CHAMPs CaRES initiative was developed as the authors (and their institute of practice) recognized the importance of ensuring that psychosocial needs of patients, families, HCWs, and members of the public were addressed while fighting a pandemic. Valuing emotional responses and needs of patients, especially that of vulnerable populations such as children, during such uncertain times is at the heart of a patient-centric healthcare system.

This initiative also reminds healthcare settings to address emotional well-being in addition to medical needs. The CHAMPs CaRES initiative stemmed from an exploratory point of view, which in turn has paved the way for further studies to develop and validate proof of concept. Future study plans could include the use of interactive and immersive technology so as to encompass and address more psychosocial needs of patients, families, and HCWs isolated in healthcare settings.

Tanuja Nair is the Head of Service for CHAMPs and is a certified child life specialist and children’s recreational teacher. She holds a Masters of Counseling and practices as a Principal Child Life Therapist at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore. Kayla Carissa Wong is a registered music therapist who is accredited in neurologic music therapy and practices on the CHAMPs team. Lily Ang Gek Lan is a child life associate and holds a Specialist Diploma in Psychology/Early Childhood Psychology; she is a member of the CHAMPs team. Koh Shuping is a child life coordinator, holds a diploma in Microelectronics, and is a member of the CHAMPs team. Pearlyn Lee Peiling is a registered art therapist who holds a Masters in Art Therapy and is a member of the CHAMPs team.

References

The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action. (2019, March). The protection of children during the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.unicef.org/media/65991/file/Technical%20note:%20Protection%20of%20children%20during%20the%20coronavirus%20disease%202019%20(COVID-19)%20pandemic.pdf

Alvarez, E. N., Pike, M. C., & Godwin, H. (2020). Children’s and parents’ views on hospital contact isolation: A qualitative study to highlight children’s perspectives. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25(2), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104519838016

Burns-Nader, S., & Hernandez-Reif, M. (2016). Facilitating play for hospitalized children through child life services. Children’s Health Care, 45(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2014.948161

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Guerrero, M. D., Barnes, J. D., Chaput, J.-P., & Tremblay, M. S. (2019). Screen time and problem behaviours in children: Exploring the mediating role of sleep duration. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16, Article 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0862-x

Imran, N., Zeshan, M., & Pervaiz, Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences Online, 36(COVID19-S4). https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2759

Kpassagou, B. L., & Soedje, K. M. A. (2017). Health practitioners’ emotional reactions to caring for hospitalised children in Lomé, Togo: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 17, Article 700. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2646-9

Lerwick, J. L. (2016). Minimizing pediatric healthcare-induced anxiety and trauma. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 5(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i2.143

Osofsky, J. D., & Osofsky, H. J. (2020). Supporting young children isolated due to coronavirus (COVID-19). Terrorism and Disaster Coalition for Child and Family Resilience. https://www.medschool.lsuhsc.edu/tdc/docs/Supporting%20Children%20and%20Adolescents%20CoronaVirus%203.9.2020.pdf

Shaw, R. J., & DeMaso, D. R. (2006). Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: Mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Skinner, E., & Edge, K. (1998). Reflections on coping and development across the lifespan. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(2), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502598384414

Tan, B. Y. Q., Chew, N. W. S., Lee, G. K. H., Jing, M., Goh, Y., Yeo, L. L. L., Zhang, K., Chin, H.-K., Ahmad, A., Khan, F. A., Shanmugam, G. N., Chan, B. P. L., Sunny, S., Chandra, B., Ong, J. J. Y., Paliwal, P. R., Wong, L. Y. H., Sagayanathan, R., Chen, J. T. C. … Sharma, V. K. (2020). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1083

United Nations Sustainable Development Group. (2020, April). Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on children. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-children

World Health Organization (2020a). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Situation report – 154. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200622-covid-19-sitrep-154.pdf?sfvrsn=d0249d8d_2

World Health Organization (2020b). Helping children cope with stress during the 2019-nCoV outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/helping-children-cope-with-stress-print.pdf?sfvrsn=f3a063ff_2&ua=1&ua=1