Rural Doctors’ Training May Be In Jeopardy

In nearly two years as a medical resident in Meridian, Mississippi, Dr. John Thames has treated car-wreck victims, people with chest pains and malnourished infants. Patients have arrived with lacerations, with burns, or in a disoriented fog after discontinuing their psychiatric medications.

Thames, a small-town Mississippi native, said the East Central Mississippi HealthNet Rural Family Medicine Residency Program has been “exactly what I was looking for.”

Unlike the vast majority of doctors, Thames sought a residency in a rural clinic instead of in a teaching hospital because his ambition is to practice in the sort of place where he grew up, where doctors are scarce. He wants to be able to handle anything that comes through the door, from infections to gunshot wounds to a woman who might deliver a baby any second.

But budget decisions in faraway Washington, D.C., may make it more difficult for Thames and other doctors who want to practice in small towns or underserved cities.

Under the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education program, which is part of the Affordable Care Act, the federal government dispenses grants to community health centers to train medical residents. The goal of the program is to address the shortage of primary care physicians in rural and poor urban areas.

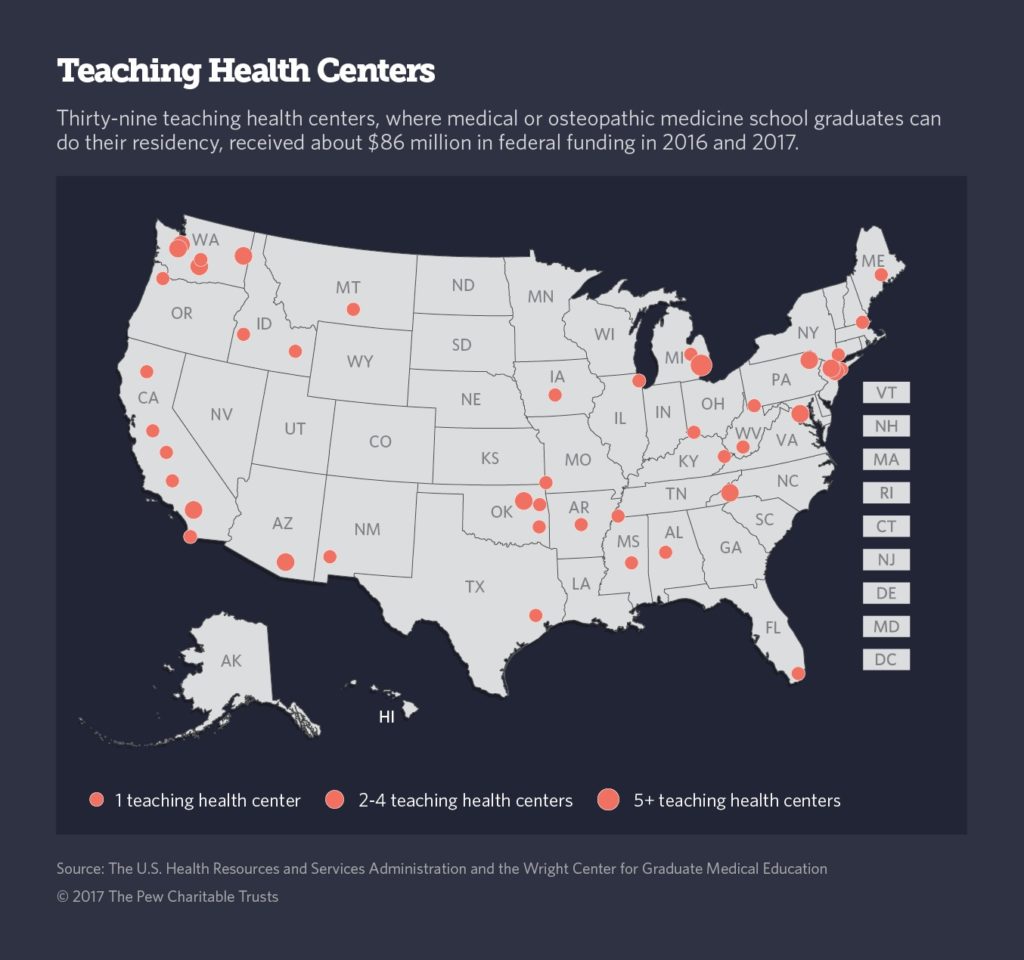

But under current law, the federal government will stop funding the program, which serves nearly 750 primary care residents in 27 states and Washington, D.C., at the end of September. Without congressional action, it might be shut down.

“The program is absolutely doing what it is designed to do, which is to put doctors in underserved areas like ours,” said Darrick Nelson, the director of Hidalgo Medical Services’ teaching health center program, which is training six residents in Lordsburg, New Mexico.

The teaching health centers have received bipartisan support in the past. But supporters worry that because the program is new, relatively small, and not as well-known as other federally funded doctor training programs, it might fall through the federal budgetary cracks.

“The greatest threat to the teaching health centers is the dysfunction in Washington,” said Dan Hawkins, a vice president at the National Association of Community Health Centers, a research and advocacy group.