Hospitals Collaborate to Prevent Wrong-Site Surgery

Hospitals Collaborate to Prevent Wrong-Site Surgery

The wrong-site surgery prevention program is one of numerous patient safety initiatives undertaken collaboratively by hospitals in the Greater Philadelphia region since 2006 under the direction of the Partnership for Patient Care (PPC). Primarily funded by Independence Blue Cross and the hospital community, PPC’s goal is to accelerate the adoption of evidence-based clinical practices by pooling the resources, knowledge, and efforts of healthcare providers and other stakeholders. The PPC is led by HealthCare Improvement Foundation (HCIF), an independent non-profit organization promoting innovative efforts to improve health services and the enhancement of public trust and confidence in the region’s health care systems. HCIF partnered with ECRI Institute, a non-profit organization researching best practices to improve patient care, to facilitate the collaborative’s shared approach.

The partnership has made a meaningful difference in improving patient safety in the Greater Philadelphia area. Building on the success of previous PPC initiatives where improvement was demonstrated through a collaborative effort, the wrong-site surgery prevention initiative adopted an approach in which participating organizations share common goals, apply interventions shown to improve performance, and share experiences with one another.

The PPC wrong-site surgery prevention program bolstered hospitals’ accelerated adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices and proposed interventions and provided a solid foundation for continued improvement and sustainability. Proposed interventions (Action Goals) were developed based on the data collection, analyses, on-site observation of select hospitals, and interviews conducted with hospital staff by staff from the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority staff analyzes near-misses and serious events reported by Pennsylvania healthcare facilities and has issued reports on wrong-site surgery prevention based on the analyses. Interventions focused on the premise that “the opportunities for wrong-site surgery are minimized when all salient information is in agreement” and “all members of the OR team assume a personal responsibility to have first-hand knowledge that the right person is getting the right procedure at the right location.” Careful attention is required to the many steps leading up to surgery in order to prevent wrong-site surgery. Starting with the patient being scheduled for surgery, there are many opportunities to make sure that the correct procedure is being performed on the correct patient, with the time out being the final opportunity to verify that information (Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority, 2007).

The 30 participating hospitals saw improvement in preventing wrong-site surgery as measured by surveys conducted at the hospitals before and after the workshops, as indicated by observational assessments conducted after each workshop, and based on the incidence of wrong-site surgery event reports submitted to the Patient Safety Authority. Based on the Authority’s reports from participating hospitals, a 72% reduction in incidence of wrong-site surgery events was demonstrated in the most recent reporting period (the 2nd quarter of 2009 through the 1st quarter of 2010) in comparison with the baseline period (the 4th quarter of 2007 through the 3rd quarter of 2008). The suggested interventions for wrong-site surgery are applicable to hospitals throughout the United States (see Figure 1: PPC Wrong-Site Surgery Prevention Action Goals).

| Crucial Process | Action Goal |

| Scheduling | Action Goal 1: Verify the accuracy of information in the request to schedule an operation including the exact description of the proposed procedure, the site, and side (as appropriate) |

| Verification & Reconciliation | Prior to patient’s arrival for surgery: Action Goal 2: Conduct a documented, independent verification and reconciliation of patient information prior to the patient’s arrival for a scheduled surgery, including schedule, consent, and surgeon’s record of history and physical examination. Day of surgery: Day of surgery: |

| Site Marking | Preoperatively: Action Goal 5: Develop and implement a protocol for marking the surgical site. Intra-operatively: |

| Time Outs | Action Goal 7: Develop a protocol for time-out involving all surgical care team members. |

| OR Turnover | Action Goal 8: Establish a policy for the hospital staff responsible for cleaning the operating room between procedures, making them responsible for identifying, removing, and dispensing found patient information/material to designated staff. |

| Organizational commitment | Action Goal 9: Promote and cultivate organizational commitment to preventing wrong-site surgery |

| Education | Action Goal 10: Educate pertinent staff on the wrong-site surgery prevention strategies and continually reinforce their importance |

| Evaluation & Feedback | Action Goal 11: Implement a method for monitoring progress of the wrong-site surgery prevention strategies and providing feedback to staff |

Figure 1: PPC Wrong-site Surgery Prevention

Why Wrong-Site Surgery Prevention?

While inconceivable to people outside of the healthcare industry, wrong-site surgery events occur in hospitals across the country. To date, the incidence of wrong-site surgery events in the U.S. is not known, but estimates indicate that it is an on-going problem. The consequences of such events vary from having no long-lasting effects on the patient (e.g., injection of an anesthetic block on the wrong-side of the body, which is then corrected by the administration of a second injection on the correct side) to those causing permanent or irreversible damage (e.g., the removal of wrong portion of bowel). In either scenario, the event can be devastating to patients, their families, and to the healthcare providers involved in the procedure. Because wrong-site surgery events are considered preventable events, there has been a concerted effort in healthcare to improve the transparency of information about such events, including required reporting as a sentinel event by the Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum’s inclusion of wrong-site surgery on its list of Serious Reportable Events (National Quality Forum, 2006). Prior to the PPC initiative, wrong-site surgery was cited as the leading sentinel event by the Joint Commission, and this still remains true today. From 1995 through March 31, 2010, the Joint Commission received 908 reports of wrong-site surgery events representing 13.4% of all Sentinel Events received (Joint Commission, 2010). Wrong-site surgery refers to several surgical errors including the wrong patient, the wrong procedure, the wrong side of the body, and/or the wrong part of an anatomic structure.

|

|||

In Pennsylvania, hospitals have reported wrong-site surgery events and near-misses to the Patient Safety Authority since June, 2004. The definition for wrong-site surgery used by the Authority is the same used by the National Quality Forum (NQF). After analyzing pertinent Patient Safety Authority data, Clarke et al. (2007) found that “over 30 months, there were 427 reports involving wrong-site surgery in an operating venue.” Of the 427 reports, 253 described events that did not touch the patient and 174 described events that did touch the patient; 83 patients had incorrect procedures done to completion.

A total of 37 wrong-site surgery events were reported to the Authority by hospitals in the Greater Philadelphia region between June 2004, and October 2007. This corresponds to one wrong-site surgery procedure every 33 days in Philadelphia-area hospitals. Overall, 19 hospitals (45% of the region’s facilities) reported one or more wrong-site surgery events; eight of these reported more than one event.

Concerned by the rate of wrong-site surgery events in the Greater Philadelphia region, the HCIF’s clinical advisory committee recommended wrong-site surgery prevention for PPC’s collaborative initiative in 2008. There was also a national focus on preventing wrong-site surgery, and the topic has synergy with other organizations’ efforts, such as the Joint Commission, the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), the American College of Surgeons (ACS), and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI).

The Approach

The PPC offered a cohesive and strategic, 4-month program facilitated by ECRI Institute to accelerate improvement and to provide participating hospitals with the foundation for continued and sustainable improvement. The program faculty was led by John R. Clarke, MD, FACS, clinical director, patient safety and quality initiatives of ECRI Institute, clinical director for the Patient Safety Authority, and a trauma surgeon, acknowledged as the nation’s leading authority on wrong-site surgery.

PPC’s regional collaborative approach involved a proactive multidisciplinary analysis of wrong-site surgery prevention processes at participating hospitals to enable more effective implementation of proposed interventions for preventing wrong-site surgery. The 30 hospitals identified key representatives (typically the OR director, surgeon champion, anesthesiologist champion, and patient safety officer) to participate in a series of interactive workshops and conference calls. Prior to the onset of the workshops, participants were provided with a research summary and Action Goals targeting crucial processes for preventing wrong-site surgery. In addition, a variety of tools (.e.g., preoperative verification checklists, scheduling form, timeout check list, observational tool) were provided throughout the initiative. Hospital participants worked with their individual hospital teams in parallel to the workshops and conference calls to analyze and redesign their own processes and to adapt and implement the Action Goals based on the unique circumstances at their facilities.

During each workshop, facilitators worked with hospital participants to select interventions for implementation in their facilities, identify challenges in implementing the interventions, and develop strategies for overcoming the challenges. In breakout sessions, teams collaborated in reviewing various scenarios where a breakdown in a crucial process had taken place (e.g., surgery for a left 5th metatarsal is on the OR schedule, but all other documents in the patient’s medical record indicate a right 5th metatarsal to be performed). The teams then came up with actions that could be taken to prevent wrong-site surgery if such an error occurred, as well as strategies for preventing similar errors from occurring in the future.

Participants got the greatest value out of meeting with the perioperative teams from other hospitals and sharing their experiences in overcoming challenges in preventing wrong-site surgery. Surgeons and anesthesiologists particularly appreciated having access to Dr. Clarke’s renowned expertise.

The workshops and conference calls provided participants an interactive forum for sharing ideas and experiences as well as hands-on assistance in helping hospitals redesign their processes and underlying systems. Participants shared the workshop progress and conference call discussions with their hospitals’ teams, thereby, providing a foundation of realistic ideas to spur and accelerate the effective adoption of key interventions.

Interventions

Interventions targeted the following crucial processes for preventing wrong-site surgery:

• Scheduling

• Verification and reconciliation of essential patient information prior to surgery

• Site marking

• Time outs

• OR turnover

Hospitals worked to implement the following Action Goals (proposed interventions) aimed at addressing vulnerabilities and potential failures in these crucial processes (see Figure 1).

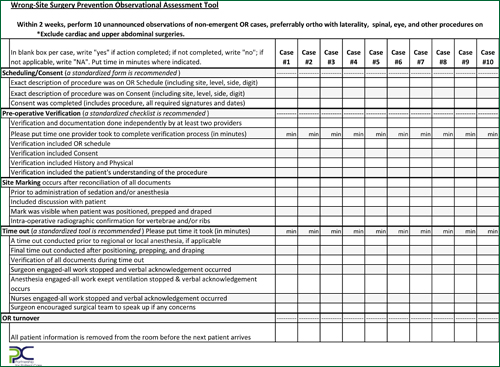

During April, 2008, participating hospitals performed 10 unannounced observational assessments of non-emergent OR cases in their facilities. Hospitals repeated the observational assessments during June, 2008. The Observational Assessment Tool (Figure 2, page 22) helped hospitals hone in on actual practices in their ORs and enabled them to identify and target processes that required further improvement.

Figure 2: Observational Assessment Tool

Over a 2-month period between baseline and follow-up observational assessments, significant improvements in observed compliance of key elements of interventions included the following:

• Pre-operative verification included OR schedule (19% improvement).

• Pre-operative verification included history and physical (12% improvement).

• Site marking occurred after reconciliation of all documents (16% improvement).

• A timeout was conducted prior to regional or local anesthesia (16% improvement).

• Surgeon encouraged surgical team to speak up in any concerns during time out (8% improvement).

Measuring and Sustaining Success

The 30 participating hospitals conducted self-assessment surveys prior to the start of the initiative, and three months later, after the last workshop, to evaluate their progress in implementing evidence-based practices and proposed interventions for effective wrong-site surgery prevention. The results of the self-assessment survey indicated an overall improvement of 7.3% in comparing aggregate follow-up to baseline scores (follow-up score of 88, baseline score of 82) during the 3-month time frame. Hospitals had high baseline scores and demonstrated incremental improvement in the follow-up assessment in areas that they had been focusing on prior to the initiative (e.g., site marking). The most dramatic improvement was demonstrated in sub-processes that had not received as much focus prior to the initiative.

The greatest improvements included the following:

• A designated hospital staff person is responsible for verifying the accuracy of information when the request to schedule an operation is received, and his/her role in the verification process is clearly delineated (26.5%).

• The facility uses a standard mechanism for verifying the accuracy of information when the request to schedule an operation is received, including verifying the exact description of the surgical procedure and specifying the surgical site (38.5%).

• When multiple procedures are performed on a patient, a separate time out is performed prior to the initiation of each procedure (18.5%).

• The hospital has established a policy for staff responsible for cleaning ORs, which outlines procedures for identifying, removing, and appropriately dispensing to a designated staff member patient information/material left from previous surgeries (52.5%).

Process measures, such as those derived from the observational assessments and from the self-assessment surveys demonstrated accelerated improvement in key elements of the proposed interventions. Over time, as interventions were more fully implemented and sustained, outcomes data demonstrated the long-term success of the PPC collaborative and the efforts of the hospitals.

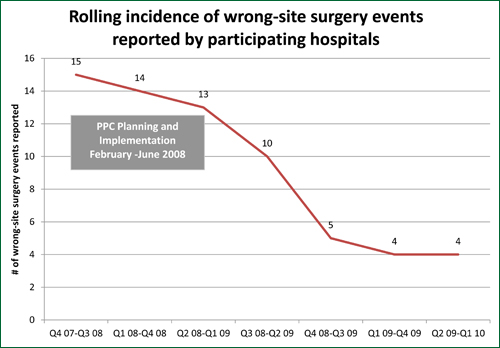

The key metric that was used to evaluate the initiative was the incidence of wrong-site surgery reports submitted to the Authority. This information was collected and reported by the Authority for the 30 participating hospitals. Due to the low incidence of events, a “rolling incidence” measure has been used to better depict the progress over time. Figure 3 (page 25) represents the rolling incidence of reports, on a four-quarter basis over 18 months, for participating hospitals. The first data point represents the number of wrong-site surgery events that were reported by the participating hospitals during the first four quarters of data collection (Q4-07 through Q3-08), which is considered the baseline period preceding and during the onset of the initiative. With each successive four-quarter data point, reports from the first quarter of the previous data point are dropped; reports from the new quarter are added. The incidence continued to decline with the most recent data point representing Q2-09 through Q1-10. This difference from 15 event reports in the baseline period to four reports in the most recent reporting period demonstrates a 73% reduction in incidence of wrong-site surgery reports. In addition, the incidence of the participating hospitals was compared to the state-wide incidence. Keeping in mind that reduction of wrong-site events was a national priority, it should be noted that the incidence of wrong-site surgery events among non-participating Pennsylvania hospitals also declined over the same 18 month period, but only by 32%.

The PPC’s regional initiative was successful in accelerating the rate of improvement in preventing wrong-site surgery for the participating hospitals. The PPC provides a solid foundation for hospitals to continue their meaningful work in incorporating evidence-based best practices and improving patient safety. Hospitals in the Greater Philadelphia region enthusiastically support efforts that provide visible demonstration of hospitals’ commitment to patient safety while enhancing the region’s recognition as a patient safety leader.

Kathryn Pelczarski, who has over 23 years experience in healthcare consulting, is director of ECRI Institute’s Applied Solutions Group. She has spear-headed ECRI Institute’s involvement in the Partnership for Patient Care (PPC), a regional collaborative to promote best practices and evidence-based medicine to improve the safety and quality of hospitals in the Greater Philadelphia area. In addition, she has led ECRI Institute’s efforts in the Regional Medication Safety Program for Hospitals, an innovative regional collaborative program for improving medication safety in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Pelczarski’s role at ECRI Institute includes management of major projects related to patient safety, technology assessment and planning, acquisition assistance, and utilization reviews. ECRI Institute is an independent, nonprofit organization dedicated to bringing the discipline of applied scientific research to healthcare to uncover the best approaches to improving patient care. For more information, contact Pelczarski at kpelczarski@ecri.org.

Pamela Braun is the director of patient safety programs at the Health Care Improvement Foundation, an independent, non-profit organization committed to building partnerships for safer health care in the Delaware Valley through the promotion of best practices. In this role, she is responsible for coordinating programs and projects funded by the Partnership for Patient Care, including the state-wide Pennsylvania Pressure Ulcer Partnership. Prior to HCIF, Braun worked for the Virtua Health System in New Jersey where she was the director of quality at the Voorhees Hospital for 5 years and then the director of clinical practice, standards and excellence, where she was responsible for the standardization of best nursing practices across the system. Braun has also worked as a healthcare consultant, a data analyst, a care coordinator and as a staff nurse. Her background includes a BSN from Villanova University and an MSN from the University of Pennsylvania. For more information, contact Braun at pbraun@hcifonline.org.

Eileen Young is assistant vice president, Crozer-Keystone Health System, responsible for evidence-based medicine program and other performance improvement initiatives. She leads the system wide peri-operative committee. Crozer-Keystone Health System is the largest employer and health care provider in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Crozer-Keystone provides a full spectrum of wellness, prevention, acute care, rehabilitation, and restorative care to the community. The health system comprises five hospitals, a comprehensive physician network of primary-care and specialty practices, and the Healthplex® Sports Club. For more information about Crozer-Keystone Health System, visit www.crozer.org.

|

Health System’s Great Catch Program Perioperative teams from Crozer-Keystone Health System’s (CKHS) four acute care hospitals engaged in the PPC Wrong-site Surgery Prevention Collaborative alongside many of their Greater Philadelphia region colleagues from other hospitals. The CKHS hospital teams were eager to participate because they recognized the benefits of joining the collaborative, working with patient safety experts such as ECRI Institute, and sharing ideas and experiences with other hospitals in the region to improve patient safety in the OR. Following the PPC Self-Assessment designed for use in the collaborative, CKHS teams adopted the following Action Goals: Building on the foundation from the PPC initiative, the CKHS perioperative committee decided it wanted to continue working on ways to prevent wrong-site surgery. Committee members were interested in understanding the vulnerabilities in their daily practice but initially struggled to identify their weak spots. The system’s hospitals current event-reporting tool is paper. The team theorized that the mechanics of using a paper tool coupled with a lack of knowledge of the importance of reporting near misses accounted for the data void. After some brainstorming, The Great Catch program was born. The strategy was simple. Create a quick, easy mechanism to report near-miss events in the perioperative arena. The committee settled on the term ‘Great Catch’ to accent the positive aspect of reporting and promote transparency and teamwork. The aim of the program is to learn from near miss events so no patient at CKHS ever suffers harm from a preventable error. The focus is on reward and recognition for reporting while fostering a positive, open atmosphere for communication. The program is straightforward. Any member of the team can fill out a 3”x5”card or leave a voice mail for the manager when he/she makes or witnesses a Great Catch. Name, date and a brief description is all that is required. Staff are publicly and formally thanked for making a Great Catch. Upon making a first Great Catch, the team member earns a lapel pin to display to others. Each quarter, a staff member is recognized for making the most significant Great Catch. Great Catches are reviewed by the system wide perioperative committee and displayed within the surgical services departments for perioperative staff. The committee uses Great Catch data to direct process redesign. In the first six months, seventy-four (74) Great Catches were reported. Forty-two percent (42%) or 31 events were related to a potential wrong-site surgery. Of those, 80% or 25 events were traced back to the surgeons’ offices. This data so impressed the committee that a multidisciplinary task force was formed to work with the network’s surgical practices, OR scheduling offices, pre-admission testing centers and patient access departments to improve the consent and scheduling process. The most recent six months of data (July 2009-December 2009) shows twenty-two percent (22%) of our Great Catches still have a potential to lead to wrong-site surgery. Some of the most outstanding Great Catches made by the perioperative staff include recognizing a patient positioned on the wrong side just about to undergo an emergency craniotomy and the discovery of a dangerous mix-up of IV solutions in anesthesia workstations. Both of these events, if undetected, would have had devastating consequences for the patients. But due to the diligence and safety awareness of CKHS staff, the near-misses have become a Great Catch! CKHS has learned that this is an evolving, dynamic program. The data will continue to help CKHS promote its patient safety focus and guide work redesign.

|